5 Reasons The U.S. Deficit Has Fallen By Nearly $5 Trillion (And Why That’s A Bad Thing)

This year’s deficit will likely be $514 billion, down about a quarter from last year’s deficit of $680 billion, which was down by more than a third from the year before.

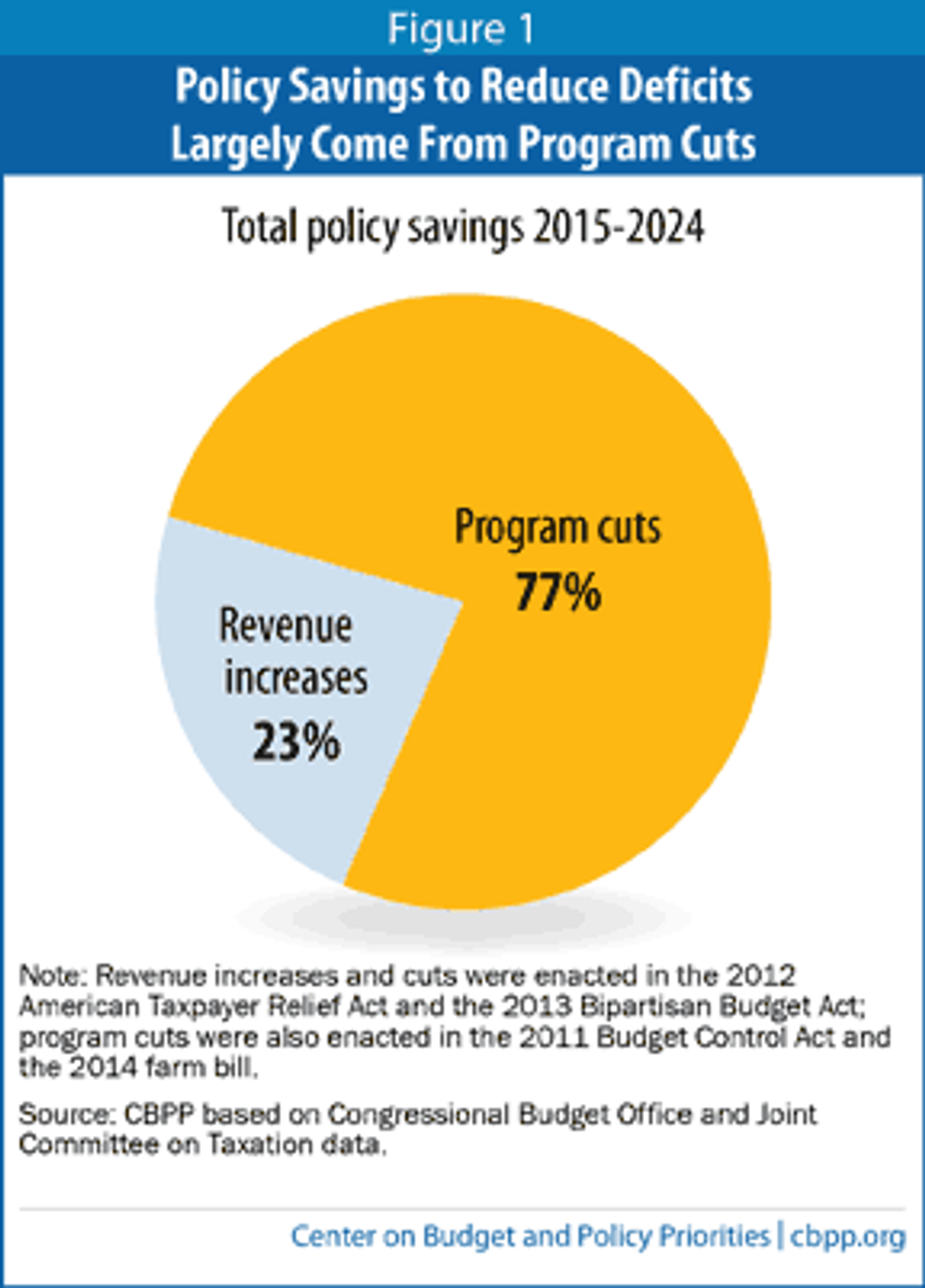

“Since 2010, projected 10-year deficits over the 2015-2024 decade have shrunk by almost $5.0 trillion, $4.1 trillion of which is due to four pieces of legislation enacted in the intervening years,” Richard Kogan and William Chen write in a new report for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

So — despite the fact that most Republicans think it’s still growing — America’s budget deficit has been reduced by two-thirds from the $1.6 trillion cost overrun President Obama inherited in 2009.

This is supposed to be good news. Centrists laud deficit reduction as if it were the only worthy goal of a government. While the improved budget outlook in the near-term has helped President Obama avoid the sort of debt limit standoff that nearly created another financial crisis in 2011, government policy is hurting the recovery and inflicting long-term damage on the economy.

Here are five reasons the deficit is falling in a way that’s hurting America’s long-term prospects.

We’ve Cut — A Lot

As we’ve tried to recover from the financial crisis, progressives have argued that the government needs to spend when the private sector cannot or is unwilling to. The left briefly won this argument with the stimulus, which was largely mitigated by cuts at the state and local levels. Since then, the conservative argument that immediate cuts would help prevent a debt disaster has prevailed, CNN Money‘s Jeanne Sahadi explains:

At its height in 2010, “discretionary spending” under Obama reached 9.1 percent of GDP. That was largely due to the stimulus law intended to dig the country out of a deep recession. But even at that high level, it wasn’t that much higher than the 40-year average of 8.4 percent and was still below the 40-year peak of 10 percent reached in 1983.

Today, levels are well below the long-term average. And the Congressional Budget Office projects that by 2023 discretionary spending will fall to 5.3 percent of GDP, the lowest since 1962.

We Raised Taxes — A Bit

While conservatives pursued a policy of only cutting spending, Democrats insisted that any deficit reduction should include new tax revenues by ending tax breaks for the rich and corporations. The combination of cutting spending and raising taxes is called austerity, and it’s the exact same policy Herbert Hoover pursued as the Great Depression began. It’s also the strategy that’s been widely used across Europe.

President Obama made a deal at the end of 2010 to extend the Bush tax breaks through 2012. The next year, he agreed to deficit reduction that resulted in the sequester that didn’t kick in until 2013. This effectively slowed the implementation of austerity, which is now in full effect in America.

The delay resulted in this country enjoying the best recovery of any nation that suffered a banking crisis in 2008.

Still, most of our deficit reduction — three-fourths — comes from reducing spending on programs that disproportionately benefit the poor. The other one-fourth comes from the richest, who have enjoyed 95 percent of the benefit of the recovery.

Growth Is Picking Up — But Not As Much As It Should Be

There was a time when government spending was deployed to fight recessions. Not this time, tho http://t.co/AtQQbChxWA pic.twitter.com/irSW4Amnqe

— Justin Wolfers (@JustinWolfers) March 11, 2014

By starving the economy of the government spending that generally helps kickstart a recovery, growth continues to be tepid. The lack of demand in turn results in corporate America sitting on a record amount of cash assets both domestically and abroad.

“Corporations hold liquid assets equal to all the money the federal government spent in 2013, 2012 and three months of 2011,” David Cay Johnston reported in Al-Jazeera America.

Why are they hoarding? Because in the absence of consumers being willing to spend, companies are trying to make a profit on their taxes, Johnston argues.

The Deficit Will Still Rise By The End Of The Decade

As Baby Boomer retirement reaches its peak at the end of the decade, the deficit will rise again. This is because though lots of cuts have been made to the federal budget, few reforms actually touch the long-term drivers of the deficit — except Obamacare.

As Baby Boomer retirement reaches its peak at the end of the decade, the deficit will rise again. This is because though lots of cuts have been made to the federal budget, few reforms actually touch the long-term drivers of the deficit — except Obamacare.

The reforms to Obamacare alone have the potential to put a dent in our long-term debt problem. In fact, if Medicare growth continues to slow at the pace it has since the Affordable Care Act became law, our long-term debt problem is essentially solved.

However, if the deficit swells, as the Congressional Budget Office expects it to by 2019, the pressure to make even more cuts to a government that’s already cut to the bone will be immense. Of course, there are less painful reforms that can be implemented now to avoid this expected crisis, including comprehensive immigration reform and reforms to Medicare that do not affect benefits.

But as much as Republicans say they care about the deficit, they are not willing to raise one dime in taxes to make a deal to cut it.

We May Never Recover From Underinvestment

The lingering underperfomance of the economy (starved of government spending, as you can see from Paul Krugman’s chart above) can be measured in multiple ways, but 6 million missing workers is probably the clearest metric.

Republicans in Congress are adding to the number of Americans out of work by letting the unemployment rate rise as much as .5 percent when they let emergency benefits for the long-term unemployed expire. Cuts to medical research inhibit long-term innovation, competition and development of new treatments. Kids being kicked off Headstart costs parents while denying kids the long-term benefits of the program.

Worst of all, we’re missing incredible opportunity to invest in our crumbling infrastructure as interest rates are near zero and millions of Americans are out of work.

Republicans campaigned and won on their vision of cutting spending in the midst of an unemployment crisis in 2010. The effects of that victory linger on lost opportunity and a future where even more senseless cuts will be necessary.