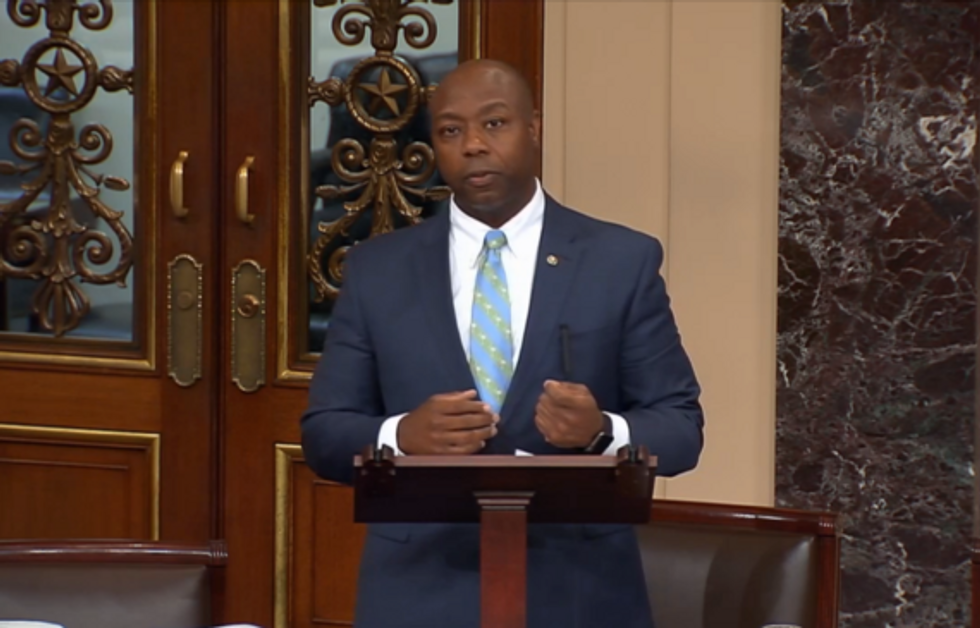

Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina was still learning the ways of Washington, he says, when he saw a police officer following his car near Capitol Hill.

“I took a left…,” he recalled in a speech Wednesday on the Senate floor, “and as soon as I took a left, a police officer pulled in right behind me.”

That was his first left turn. His second came at a traffic signal. The patrol car was still following him. Scott took a third left onto the street that led to his apartment complex.

It was his fourth left, turning into his apartment complex, that brought the blue lights on. “The officer approached the car,” Scott recalled, “and said that I did not use my turn signal on the fourth turn. Keep in mind, as you might imagine, I was paying very close attention to the law enforcement officer who followed me on four turns. Do you really think that somehow I forget to use my turn signal on that fourth turn? Well, according to him, I did.”

Oh, did I mention that Tim Scott is African-American? He’s the only black Republican in the Senate and the first to be elected from the South since 1881.

He did not get there by being a liberal or a Black Lives Matter radical. He’s a “pro-life,” anti-Obamacare and NRA-endorsed conservative.

He is also, whatever else you may think of his politics — which are more conservative than mine — a very likeable and thoughtful businessman from North Charleston whose family, as he likes to say with patriotic pride, “went from cotton to Congress in one lifetime.”

Yet, issues such as police conduct and public safety have become personal for Scott. It was in his hometown, North Charleston, S.C., last year that a cellphone video showed Walter Scott (no relation), an unarmed 50-year-old black man, shot to death by a police officer from whom he was running away.

Two months later a gunman fatally shot nine people, including friends of Scott, at Charleston’s historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Scott calls for a halt to abuses by police, but he also wants fairness for police and improved law enforcement.

One tragedy illustrated the dangers of bad policing. The other illustrated why we need good police.

So when Scott stood on the Senate floor to declare and decry a “trust gap” between law enforcement officers and black communities, he was worth hearing.

“Please remember that, in the course of one year, I’ve been stopped seven times by law enforcement officers,” Scott declared in the widely covered and retweeted speech. “Not four, not five, not six but seven times in one year as an elected official.

“Was I speeding sometimes? Sure. But the vast majority of the time, I was pulled over for nothing more than driving a new car in the wrong neighborhood or some other reason just as trivial.

“I do not know many African-American men who do not have a very similar story to tell,” said Scott, “no matter the profession, no matter their income, no matter their disposition in life.”

A young former staffer of Scott’s grew so frustrated over being stopped by District of Columbia police, the senator said, that he replaced the car with “a more obscure form of transportation. He was tired of being targeted.”

“There is absolutely nothing more frustrating, more damaging to your soul,” said Scott, “than when you know you’re following the rules and being treated like you are not.”

On that note, Scott asked for nothing in his speech, except empathy, a sincere effort to understand what others are going through — which in itself is asking a lot from some people.

“Today,” he said, “I simply ask you this: Recognize that just because you do not feel the pain, the anguish of another, does not mean that it does not exist. To ignore their struggles, our struggles, does not make them disappear. It simply leaves you blind and the American family very vulnerable.”

Well said. Folks who respond to complaints of racial discrimination by police by bringing up black-on-black crime need to hear what Tim Scott is trying to tell them. Fighting crime without fighting police misconduct leads to more crime. We need to get rid of both.