As a statue paying tribute to civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks was unveiled in Washington, D.C., the Supreme Court heard arguments in the case of Shelby County v. Holder, which will decide the Constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that bears Ms. Parks’ name.

Section 5 of the VRA requires election officials in selected states and regions, mostly in the South, to pre-clear any changes to voting laws. This provision has been called the “cornerstone of civil rights law” in America.

“Is it the government’s submission that citizens in the South are more racist than citizens in the North?” asked Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts.

Solicitor General Donald Verrilli said no.

Roberts noted that Massachusetts had the lowest turnout rate of black voters while Mississippi had the highest. He and all of the conservative justices on the court expressed skepticism of the continued relevance of a law that was originally intended to be an emergency accommodation.

The Voting Rights Act was renewed for 25 years by a Republican Congress and signed by George W. Bush in 2006. But right-wing organizations and donors have waged a two-decade campaign to destroy Section 5.

The law was deemed Constitutional in 1999, before Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito joined the Court. Justice Clarence Thomas has previously called Section 5 unconstitutional and Justice Antonin Scalia’s antipathy to the law was clear to all in attendance.

Scalia called Section 5 a “perpetuation of racial entitlement” and suggested that Congress could never be convinced to let the law lapse. “They’re going to lose votes if they vote against the Voting Rights Act. Even the name is wonderful.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor twice asked Scalia, “Do you think Section 5 was voted for because it was a racial entitlement?” He did not answer either time.

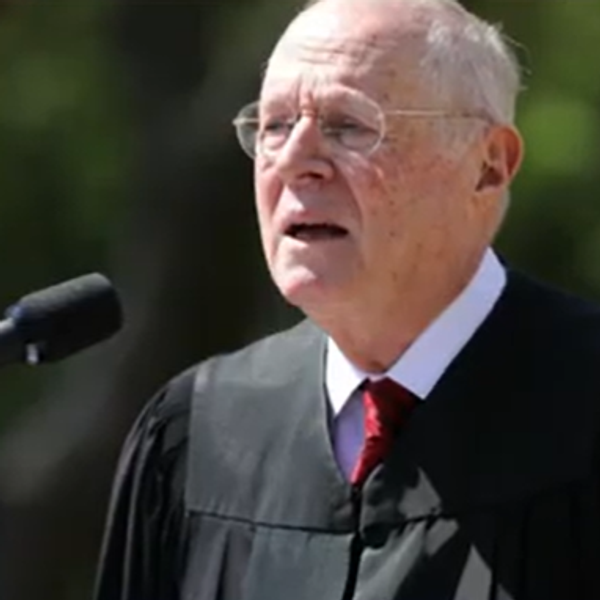

Experts believe that Justice Anthony Kennedy will be the deciding vote on the case. He appeared extremely troubled by the idea of pre-clearance, saying it put some states under the “trusteeship of the United States government.”

“Times change,” Kennedy said at one point.

“Kennedy asked hard questions — that’s his job,” Myrna Perez, a senior counsel with the Brennan Center, told the Washington Post‘s Greg Sargent. “But the questions didn’t signal the law’s demise.”

Verrilli pointed out that jurisdictions can “bail out” of the pre-clearance requirement once they’ve demonstrated a 10-year discrimination-free record — nearly 250 of the 12,000 state, county and local governments covered by the law have bailed out.

Justice Elena Kagan noted that the covered jurisdictions hold 25 percent of the U.S. population, but account for 56 percent of voting-rights lawsuits.

Sotomayor asked Bert Rein, the lawyer representing Shelby County, Alabama, “Why would we vote in favor of your county, whose enforcement record is the epitome of the reasons that cause this law to be passed in the first place?”

In his brief, Rein argued that conditions that made the law necessary no longer exist.

The Nation‘s Ari Berman, who was at the hearing, noted that the rash of legislative attempts to restrict voting rights since 2010, which he’s called the “GOP’s War on Voting,” never came up during the arguments.

Photo credit: AP Photo/Evan Vucci