Florida Among Nation’s Toughest States To Have Voting Rights Restored

By Dan Sweeney and Lisa J. Huriash, Sun Sentinel (TNS)

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. — Commit any felony in Florida and you lose your right to vote for life — unless the governor and the clemency board agree to give that right back to you.

The result: More than 1.6 million Floridians — about 9 percent — cannot vote, hold office or serve on a jury, according to The Sentencing Project, a prison reform group. In most states, the percentage is less than 2.

Only two other states have that tough a policy.

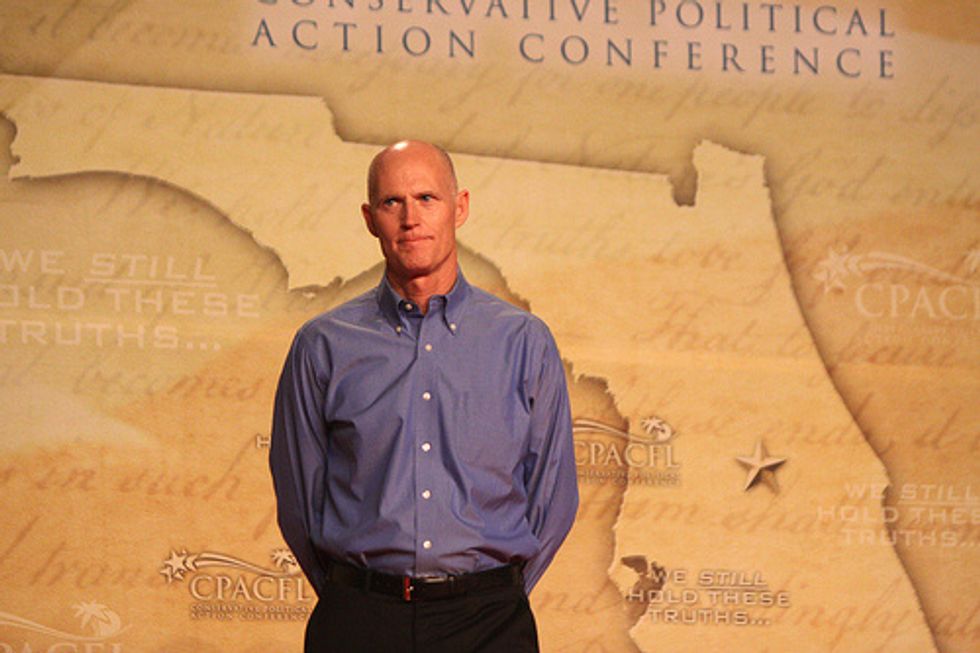

Getting back those rights has become far tougher in the past four years. Under Gov. Rick Scott, 1,534 nonviolent felons had their rights restored. More than 11,000 others applied but are still waiting for an answer.

Under former Gov. Charlie Crist, the clemency board automatically restored the rights of nonviolent offenders who served their time — and a total of 155,315 got them back during his four-year term.

Now, some members of the Florida Legislature, as well as voting rights groups, are pushing a state constitutional amendment that would return the vote to convicted felons — except those found guilty of murder or sexual offenses — after they have served their time and completed parole and probation.

“After someone has served their sentence, they shouldn’t keep being punished for the rest of their life,” said Jessica Chiappone, a Boca Raton lawyer who chairs the political committee Floridians for a Fair Democracy.

Laws nationwide on whether convicted felons can vote vary widely. In Vermont and Maine, the currently incarcerated can vote by absentee ballot, while Florida, Kentucky and Iowa are at the harshest end of the spectrum, mandating that all ex-felons lose their civil rights until they petition to have them back. In other states, ex-felons generally get their rights back when they get out of prison or off probation.

Among Florida’s black population, one in four can’t vote, even though just 17 percent of the state’s population is black.

“The law has a disproportional effect on African-Americans,” said Erika Wood, a professor at New York School of Law who ran the Brennan Center for Justice’s right-to-vote project. “There are just dramatic numbers of people who are not eligible to vote because of this rule. It’s anathema to what our democracy is all about.”

But state Attorney General Pam Bondi, who rewrote the guidelines in 2011 to make them more stringent, does not see voting rights in the same light.

“This issue is about felons proving they have been rehabilitated before having their civil rights restored,” said Bondi spokesman Whitney Ray.

Rosalind Osgood had her rights returned in 2010. Today, she is a Broward School Board member and head of the Mount Olive Development Corporation, which provides assistance to needy locals.

But back in the late 1980s, she was a drug addict living on the streets, twice convicted for cocaine possession. “The more I started using drugs, the more I started needing more drugs,” she said.

Finally, after coming before a judge while pregnant, Osgood turned her life around. She started hitting 12-step programs and finished college. But she said she felt apart from society, unable to vote despite all the gains she had made.

“Our system is supposed to rehabilitate, to hold you accountable when you go against the law, but to rehabilitate you so you can come back into society,” she said. “I don’t understand why people’s rights aren’t restored. As CEO of the Mount Olive Development Corporation, it’s very hard for me to help people rebuild their lives when they run into these barriers.”

Civil rights can be restored only by the governor and Cabinet, who act as the clemency board and meet four times a year. The application process requires a five-year wait for less-serious felonies and seven years for others, along with an application form and, for each felony count, certified copies of the charging document, judgment and sentencing from the clerk of the county where the felony occurred.

“It’s time-consuming for people that are trying to make a difference and get back on the right track,” Chiappone said. “The system in place makes it easier not to fight that fight.”

It wasn’t always so difficult. In 2007, under Crist, Florida relaxed its rules as part of a nationwide trend. Before that, under Gov. Jeb Bush, sentencing forms were not required of people trying to get their rights back, and there was no wait period for the less-serious felonies.

But once Gov. Rick Scott and Bondi were elected in 2010, Bondi tightened the rules so they were tougher than under Bush.

“The proposed changes are intended to emphasize public safety and ensure that all applicants desire clemency, deserve clemency, and demonstrate they are unlikely to reoffend,” Scott said at the time.

Because Florida’s Constitution mandates that all felons lose their civil rights until the clemency board acts, the constitution would need to be amended for any change.

Floridians for a Fair Democracy plans a petition drive to make that happen.

Chiappone, the group’s chairwoman, served seven months in a federal prison in the 1990s on drug charges. But by 2008, she was in law school and hoping to pass the Florida Bar exam, which requires test-takers to have civil rights.

Chiappone said that she waited five years to have her rights restored. She said that the clemency board lost her paperwork, then the new guidelines came in, and the new rules applied retroactively.

“It’s incredible, the difficulties you face,” Chiappone said. “And if it’s about integrating people into society, it should be easier, not harder. It’s illogical.”

State Sen. Jeff Clemens (D-Lake Worth) and state Rep. Clovis Watson (D-Alachua) agree. They have filed bills asking the legislature to place a constitutional amendment on the ballot in 2016 that would return the vote to nonviolent felons who have served their time and completed parole and probation.

Bondi’s office does not support these efforts, though the attorney general is open to some reforms. She supported a 2011 law that said state agencies can’t deny applications for licenses, permits or employment based on civil rights status. But private groups, such as the Florida Bar, can still require it.

That irks Chiappone and Osgood.

“If we want felons to be functional members of society, we can’t talk out both sides of our mouth,” Osgood said. “On one side, we want people to get jobs, and work and go to school, and earn their way and make a valuable contribution. But over here, we hold their purse strings, literally, when we don’t restore their rights.”

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr