More than 15 years after her debut on the public stage, Kathleen Willey – the Virginia society matron who accused Bill Clinton of groping her in an alcove off the Oval Office – has returned with a vengeance. On Tuesday evening, she appeared on Fox News with anchor Megyn Kelly. Her new message is that Hillary Rodham Clinton “is the war on women,” supposedly guilty of directing a covert campaign to silence women like Willey who were wronged by her husband, the former president. She has also suggested that the Clintons murdered her own husband, Ed Willey, a Richmond lawyer who shot himself after his embezzlement of a client’s funds was exposed.

Willey offered no evidence for her conspiratorial calumnies against the former Secretary of State, but that was hardly surprising. To those who have observed her closely, Willey’s inventive imagination has long been her most notable quality. As an immunized witness for Kenneth Starr’s Office of Independent Counsel, which probed President Clinton’s testimony in the Paula Jones sexual harassment case, Willey proved so unreliable that her testimony could not be used – and the OIC considered prosecuting her for lying to them.

The following excerpt from The Hunting of the President— the bestselling 2000 book about the Clintons and their accusers by Joe Conason and Gene Lyons – indicates that Willey’s honesty and motives were doubtful even before Newsweek reporter Michael Isikoff published her account of Clinton’s alleged assault on her.

During the summer of 1997, the Newsweek reporter had approached Linda Tripp, a White House friend of Willey who later became a key Starr witness in the Monica Lewinsky affair, to validate the stunning story after he first interviewed Willey. But as Tripp explained to Isikoff, her recollection of Willey’s own behavior toward Clinton did not even remotely resemble what the supposedly aggrieved woman had told him.

When she got home on the evening of Isikoff’s visit, Tripp called Willey for the first time in almost three years and bluntly accused her of lying to the Newsweek reporter.

“Kathleen, what are you doing?”

Without a hint of doubt, Tripp recalled, Willey coolly rebuffed Tripp’s objections. “You must be misremembering, Linda…Of course it was sexual harassment. I don’t know why you’re now saying that I wanted it.”

“Kathleen, because we talked about it for months before it happened, because you chose your outfits, because you positioned yourself, because you flirted, because you looked for every reason to get in [to see Clinton privately],” Tripp remembered saying, when she described their conversation later. “Why are you now saying that this came as a huge surprise and he assaulted you?

As Tripp testified in vivid detail, Willey’s sudden claims of indignation didn’t remotely resemble the truth about her feelings toward Clinton in 1993. Not only had she been “happy” after the president’s allegedly feverish embrace in the Oval Office, but she and Tripp had been scheming together for months to stage her seduction of him. Tripp claimed her marriage to Ed Willey was loveless, on the verge of divorce. She wanted to move to Washington and have an affair with Clinton. “Kathleen [felt] that it had the potential to be a relationship that would be agreeable to the two of them.” (Tripp’s portrait of Willey was corroborated in sworn testimony by Harolyn Cardozo, another friend of Willey’s and wife of Michael Cardozo, a Washington attorney and the former director of the President’s Legal Expense Trust. Cardozo recalled Willey boasting that she might become “the next Judith Exner” [one of President Kennedy’s mistresses] and pondering how to advance the relationship. We’ve got to get Hillary out of town!” Cardozo recalled her saying, only half in jest.)

Well before the Oval Office incident, Willey had taken Tripp on as her secret romantic adviser, calling to chat in the evenings about her obsession with the president. Tripp admitted encouraged the infatuation because in her view both Clinton and Willey were stuck “in not very good marriages, and it just seemed to be as consenting adults.” She also enjoyed the intrigue, helping Willey gain access to the president’s daily schedule so the pretty matron could arrange to bump into him, always dolled up “to catch his eye.” The two friends would talk about creating the conditions for a tryst, escaping the Secret Service, and “the logistics of how this could work,” Tripp testified. They had even discussed a specific location. Debbie Siebert, a mutual friend whose husband had been named ambassador to Sweden, had quite innocently invited Willey to use their empty house on the water in Annapolis.

After she had finally met with Clinton alone in the Oval Office, Willey had hurried to find Tripp, and met her coming upstairs in an elevator. Right away Tripp noticed her usually immaculate friend’s fed face, bare lips, and mussed hair. “Do you have a lipstick? Come down with me.” Flushed and breathless, Willey dragged her outside to a parking lot and told her about Clinton’s ardent, “forceful,” embrace in graphic terms. Willey praised him, Tripp recalled , as a “great kisser,” and said she had kissed him back despite her fear that someone would walk in on them.

The next day Willey learned that her husband was dead. To Tripp, however, she seemed oddly disengaged in the aftermath of his suicide, even from the practicalities of arranging his funeral. She “didn’t cry, she didn’t dwell or even speak much about Ed,” according to the testimony of Tripp, who spoke with her frequently around that time. Instead, Kathleen talked “almost obsessively” about her encounter with the president. Willey worried that her late husband’s suicide “would be enough to spook [Clinton] for at least a year, that…he would not have anything to do with her on a personal level after this because of the tragedy.

“And I remember she received a call from [Clinton aide] Nancy Hernreich saying that the president wanted to call at an appropriate time to extend his condolences, and Kathleen called back because she apparently had had people at the house helping her and left a message [for the president]: ‘You can call anytime.’”

But as she and Tripp argued over the telephone many months later, Willey kept insisting that Clinton had subjected her to an unwanted mauling. And to Tripp’s astonishment, she realized that Willey “believed everything she was telling me that night.” Willey also confided that what she had really wanted from Clinton was lucrative employment. And although Tripp didn’t realize it that night, Willey’s financial desperation was an important clue to her behavior.

…

The Newsweek reporter might have put aside the confusing tale of Kathleen Willey, at least temporarily, except for the intervention of the Supreme Court. After the justices ruled unanimously on May 28 that the Jones case should proceed, Isikoff realized that Willey might be the plaintiff’s most valuable witness in discovery and, if necessary, at trial. Jones attorney Joe Cammarata was already aware of her existence if not her identity, and was likely to find her sooner or later. Isikoff had to move quickly. His editors urged him to keep reporting until he had enough to publish.

Isikoff called Willey again in early June, hoping to convince her to go on the record. “Your story is going to have to come out,” he told her. “It’s inevitable.” She still refused.

Her apparent reluctance may have been a sham, although Isikoff had no way of knowing that. She too may have realized that the Supreme Court decision had increased her market value. The same week that she rejected the reporter’s entreaties to go public with her story, she was attempting – as Tripp had done before her – to sell it as a tell-all book. Her literary model was Faye Resnick, the friend of Nicole Brown Simpson whose potboiling account of the events leading up to the O.J. Simpson murder trial had been a quickie bestseller, and a Kathleen Willey favorite.

Willey’s telephone records showed that during the second week of June she had made several calls to top New York literary agencies. She called both International Creative Management and Janklow and Nesbit on June 6. (That same day she also called Publishers Weekly and New York magazine; her three calls to New York, she eventually testified, concerned her subscription to the glossy weekly.) She called both firms again on June 11. While she received little encouragement at either agency, she did get to make her pitch to Lynn Nesbit’s associate Tina Bennett. Under oath, Willey later explained these calls as attempts to seek public relations advice, because she anticipated that Isikoff’s article about her experiences would soon appear in Newsweek and cause a media explosion.

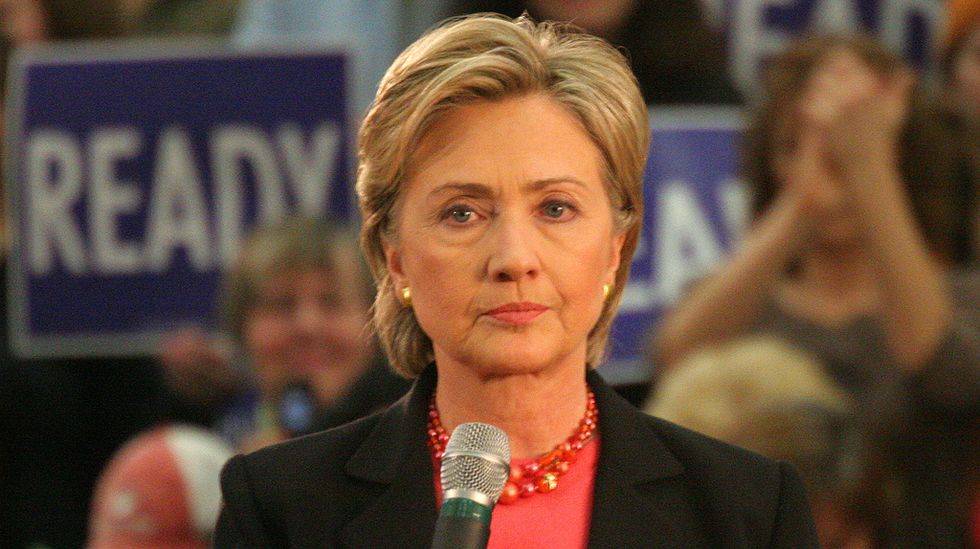

Photo: Aaron Web via Flickr