Originally posted at The Washington Spectator

After 227 years of history, how should we judge the United States Supreme Court? All of my years of studying, teaching, and practicing Constitutional law have convinced me that the Supreme Court has rarely lived up to lofty expectations and far more often has upheld discrimination and even egregious violations of basic liberties.

My disappointment in the Court is historical and contemporary. Its preeminent task is to enforce the Constitution in the face of majorities that would violate it. The Court is thus especially important in protecting minorities and in safeguarding rights in times of crisis when passions cause society to lose sight of its long-term values.

For the first 78 years of American history until the ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865, the Court enforced the institution of slavery. For 58 years, from 1896 until 1954, the Court embraced the noxious doctrine of separate but equal and approved Jim Crow laws that segregated every aspect of Southern life. Nor are egregious mistakes by the Supreme Court on race a thing of the past. The Roberts Court has furthered racial inequality by striking down efforts of school boards to desegregate schools and by declaring unconstitutional crucial provisions of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Court also has continually failed to stand up to majoritarian pressures in times of crisis. During World War I, individuals were imprisoned for speech that criticized the draft and the war without the slightest evidence that the expression had any adverse effect on military recruitment or the war effort. During World War II, 110,000 Japanese-Americans were uprooted from their lifelong homes and placed in what President Franklin Roosevelt referred to as “concentration camps.”

During the McCarthy era, people were imprisoned simply for teaching works by Marx and Engels, and Lenin. In all of these instances, the Court failed to enforce the Constitution. Most recently, the Roberts Court held that individuals could be criminally punished for advising foreign organizations, designated by the United States government as terrorist organizations, as to how to use the United Nations for peaceful resolution of their disputes or how to receive humanitarian assistance.

For almost 40 years, from the 1890s until 1937, the Court declared unconstitutional more than 200 federal, state, and local laws that were designed to protect workers and consumers. The Court even declared unconstitutional the first federal law designed to prevent child labor by prohibiting the shipment in interstate commerce of goods made by child labor. Minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws were frequently invalidated.

Even the areas of the Supreme Court’s triumphs, like Brown v. Board of Education and Gideon v. Wainwright, accomplished less than it might seem. American public schools remain racially separate and terribly unequal. Criminal defendants in so many parts of the country, including in death-penalty cases, have grossly inadequate lawyers.

The Court’s decisions from the last few years — preventing employment discrimination suits and class actions against large corporations, keeping those injured by misconduct of generic drug makers from having any recovery, denying remedies to those unjustly convicted and detained — illustrate what has historically been true: The Court is far more likely to rule in favor of corporations than workers or consumers; it is far more likely to uphold abuses of government power than to stop them.

What should we do about it?

Some scholars urge the abandonment of judicial review, but I reject that conclusion. The limits of the Constitution are meaningful only if there are courts to enforce them. For those I have represented over my career — prisoners, criminal defendants, homeless individuals, a Guantánamo detainee — it is the courts or nothing.

But I believe that there are many reforms that can make the Court better and, taken together, make it less likely that it will so badly fail in the future. I propose a host of changes, including instituting merit selection of court justices, creating a more meaningful confirmation process, establishing term limits for court justices, changing the Court’s communications (that is, televising its proceedings), and applying ethics rules to the court justices.

The Supreme Court’s decisions affect each of us, often in the most important and intimate aspects of our lives. I think that we need to focus on the Court’s long-term and historical performance. If we do, it is a disturbing picture and there is only one possible verdict: The Court is guilty of failing to adequately enforce the Constitution.

But it can and must get better in the years and decades ahead.

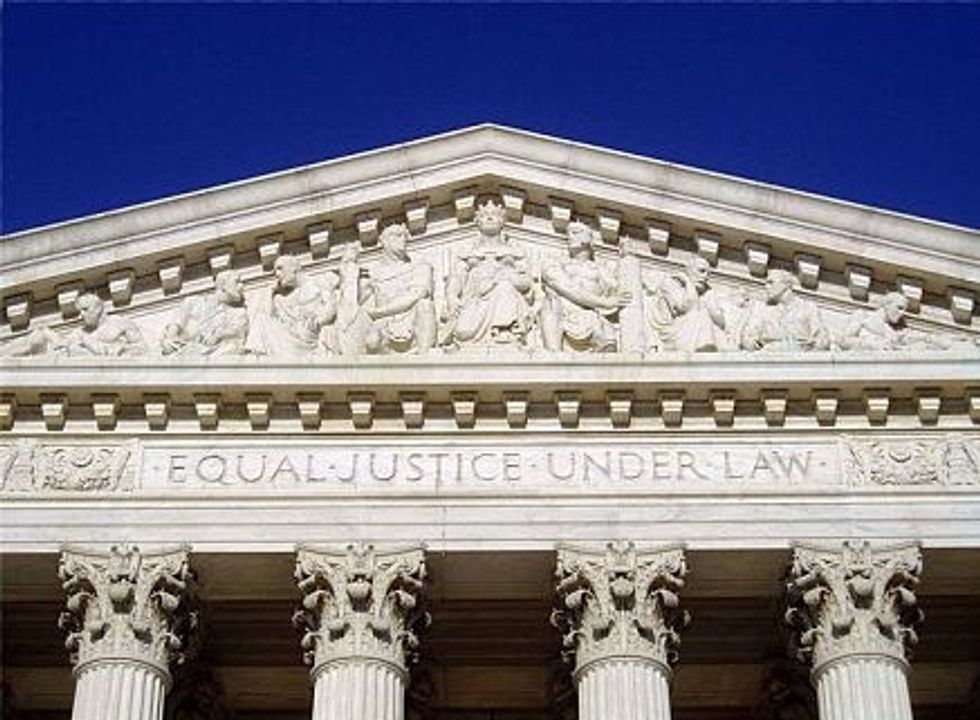

Photo: Matt H. Wade via Wikimedia Commons