Helicopter parents, start your engines.

They’re revising the SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test) again, and you know what that means. More weeping, wailing and gnashing of teeth. More complaints about the unfairness of life and of American society. More free-floating status anxiety projected onto adolescent children already uneasy about leaving the parental nest. Or eager to escape it.

Observing the hullabaloo, it’s tempting to wonder if Americans haven’t turned into a nation of crybabies. The New York Times, which covers the politics of college admissions the way Ring Magazine covers welterweight title bouts, published a classic whine by a Maine English professor. “Our children,” she lamented “precious, brilliant, frustrating, confused souls that they are, are more than a set of scores.”

They’re certainly that. Intellectually brilliant, however, most are not. Nor are most of you reading this column, and certainly not the fellow writing it. Using words like “brilliant” when what we mean is “unique” or “beloved” is part of the problem. Regardless of how carefully the College Board revises the exam, only one percent can be squeezed into the 99th percentile.

Hence the intense feelings of fear and unworthiness described by Prof. Jennifer Finney Boylan, who characterizes her own experience of taking the SAT as “a mind-numbing, stress-inducing ritual of torture.” She even complains that it’s like totally unfair to expect American adolescents to be wide-awake and functional at 8:30 AM. Boo-hoo-hoo.

As a girl, Boylan had set her heart upon Wesleyan College. “No single exam, given on a single day,” she complains “should determine anyone’s fate.” God forbid she should have to attend, say, the University of Connecticut or some less prestigious public university. God forbid she should join the Army.

Originally conceived in the 1920s as a means of identifying academically talented individuals whose abilities might otherwise be overlooked, the SAT has done a reasonably good job of doing so over the years.

No, it’s never been perfect. “You can probably think of someone who did poorly on the SAT and yet graduated summa cum laude from college,” concedes David Z. Humbrick, a psychology professor at Michigan State. “You can probably also think of someone who did spectacularly well on the SAT but who flunked out of college after a semester.”

Or who dropped out of college and founded Microsoft, for that matter.

“The SAT is largely a measure of general intelligence,” Humbrick adds. “Scores on the SAT correlate very highly with scores on standardized tests of intelligence, and like IQ scores, are stable across time and not easily increased through training, coaching or practice.”

Intelligence as college professors measure it, that is. A person can have extremely high verbal ability without the slightest mechanical aptitude. We’ve all known math whizzes who are total space cadets. I’ve been around Rhodes Scholarship finalists who can’t tell if a dog is friendly or not.

My own SAT scores were somewhat higher than my wife’s. But I can’t tell you how many times she’s asked me, “Didn’t you see her face when you said that?”

Um, actually no. Sorry.

I’d be a worse diplomat than Dick Cheney.

Reading the Times’ coverage of the latest SAT overhaul, then, I was surprised at how little the test is actually changing. For example, they’re making the essay part optional. Good. The grading of a couple of million papers couldn’t have been anything but farcical. Besides, colleges were mainly using it to figure out whose mommies wrote their entry applications.

The new SAT is intended to evaluate what College Board president David Coleman calls “evidence-based” reading, writing and mathematical reasoning. “Students will be asked to do something we do in work and in college every day…analyze source materials and understand the claims and supporting evidence.”

It’s important to be realistic about what such tests say and don’t say about the individuals who take them. I once did a little routine for a classroom of SAT-proud college freshmen based upon my experience of once riding in an elevator with a half-dozen members of the New York Knicks.

Talking about height made it easier make an analogy to a subject often shrouded in obfuscation. A one-time high school basketball player, I’m probably around the 90th percentile height-wise. Among NBA players, I was the shortest man around—an oddly uncomfortable experience.

It’s the same with every other measurable human trait, intelligence included. Chart them, and you end up with a bell curve. Almost everybody’s clustered near the mean. The practical differences in intellectual ability between, say the 75th and 95th percentile aren’t half as great as people pretend.

Real genius is too rare for a crude instrument like the SAT to measure. You can have verbal and math scores in the 700s without being very smart at all.

So your kid’s scores are interesting, but they hardly add up to fate or destiny, either way.

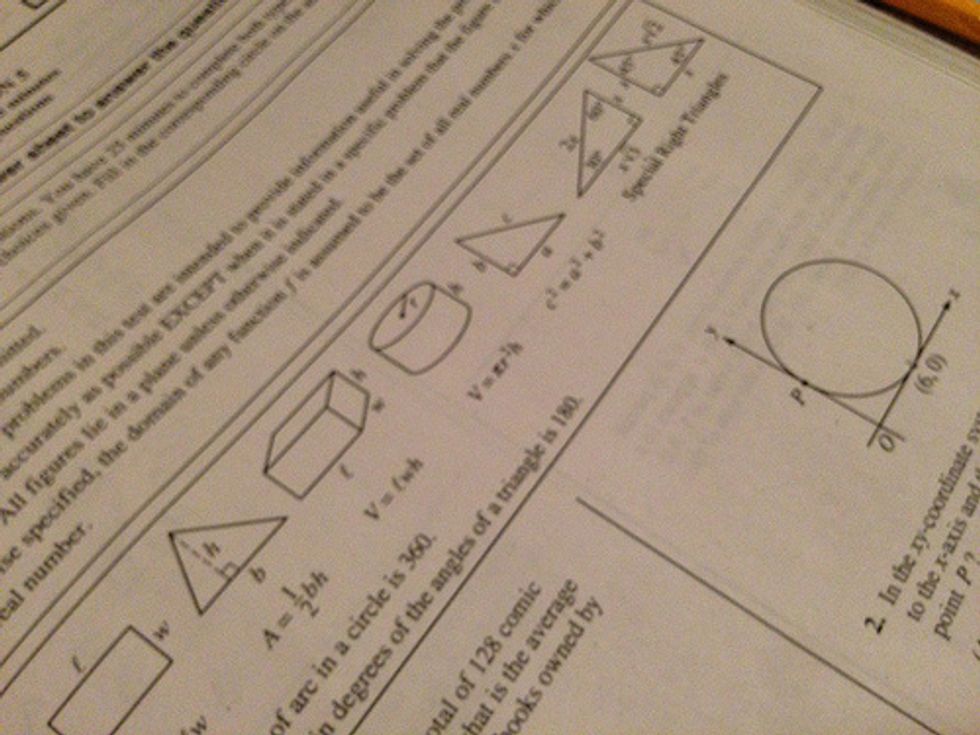

Photo: Butz.2013 via Flickr