Obama Should Look To Roosevelt In Fight Against Inequality, Right Wing

Seventy years ago, on January 11, 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt delivered his 11th Annual Message on the State of the Union. The United States was at war. But the president spoke not only of the struggle and of what Americans had to do to hasten victory over the Axis Powers. He also spoke of what Americans needed to do to win the peace to come. Reaffirming his administration’s commitment to the vision he had articulated in his 1941 Annual Message – the vision of the Four Freedoms: Freedom of speech, Freedom of worship, Freedom from want, Freedom from fear – Roosevelt now called for an Economic Bill of Rights for all Americans.

As President Obama prepares his 2014 State of the Union address for delivery on January 28, with the question of his second-term legacy no doubt in mind and midterm elections on the near horizon, he would do well to attend to FDR’s 1944 Message. Our own challenges are not those of 1944. But in the wake of the tragedies, crises, painful obstructions, and compromises of the past 15 years, and in the face of continuing right-wing and corporate class war against working people, they are no less daunting – and we are no less eager to start addressing them.

By January 1944, the United States and its allies had turned the tide of war. The Normandy invasion was still months away, but Allied forces were clearly advancing both east and west. And yet Americans were anxious – anxious not only about the lives of their loved ones in uniform and how long it might take to defeat Germany and Japan, but also about what might actually follow the victory. Many worried that the end of the war effort would see the return of severe economic difficulties and high unemployment, if not a new depression.

Roosevelt was well aware of those anxieties. But he knew what Americans could accomplish and he intended to speak to them as he had in 1933 — when he invited them to beat the Great Depression taking up the labors and struggles of recovery, reconstruction, and reform known as the New Deal — and again in 1941, when he mobilized them to go “All Out!” against fascism and imperialism in the name of the Four Freedoms. Now as before he would not ask them to lay aside or suspend their democratic ideals and hard-won achievements for the duration, but urge them to rescue the nation from destruction and tyranny by not only fighting and defeating their enemies, but also making America freer, more equal, and more democratic in the very process of doing so.

Roosevelt also knew full well that Congress would never endorse an economic bill of rights. Dominated since 1938 by a conservative coalition of Republicans and southern Democrats, Congress had been doing everything it could to terminate the New Deal, limit the rights of workers and minorities, and block new liberal initiatives. And yet he had good reason to believe that most of his fellow citizens would embrace the idea. Polls showed that the vast majority of Americans saw the war in terms of the Four Freedoms, and understood the battles of not just the past three years, but the past 12 years, in terms of enhancing American democratic life. In fact, 94 percent of them endorsed old-age pensions; 84 percent, job insurance; 83 percent, national health insurance; 79 percent, aid for students; and 73 percent, work relief. Pollster Jerome Bruner would observe: “If a ‘plebiscite’ on Social Security were to be conducted tomorrow, America would make the plans of our Social Security prophets look niggardly. We want the whole works.”

After outlining a set of policies to speed up the war effort, the president looked ahead: “It is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard of living higher than ever before known.” And in favor of that he proposed the adoption of a Second Bill of Rights.

“This Republic,” he said, “had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights… They were our rights to life and liberty. As our Nation has grown in size and stature, however – as our industrial economy expanded – these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.” But, he continued: “We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. ‘Necessitous men are not free men.’” And evoking Jefferson, the Founders, and Lincoln, he contended that “In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident,” and “We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all regardless of station, race, or creed.” This Second Bill of Rights included:

The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the Nation;

The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

The right of every family to a decent home;

The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

The right to a good education.

In sum, he stated: “All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being.”

Roosevelt did not leave it there, however. Distinguishing “clear-thinking businessmen” from the rest, he alerted his fellow citizens to “the grave dangers of rightist reaction.” And he then put Congress itself on the spot: “I ask Congress to explore the means for implementing this economic bill of rights – for it is definitely the responsibility of Congress to do so.” Finally, linking the question of addressing the needs of the war veterans to that of enacting the new bill of rights in a universal program of economic and social security, he declared: “Our fighting men abroad – and their families at home – expect such a program and have the right to insist upon it.”

The labor movement quickly mobilized around the president’s proposal. Liberal politicians, editors, academics, and theologians enthusiastically joined in a newly created National Citizens Political Action Committee to bolster labor’s efforts. Civil rights organizations firmly embraced the promise they heard in FDR’s words. And Americans energetically rallied as workers, consumers, and citizens.

Roosevelt himself did not retreat in the autumn presidential campaign. He not only reiterated his call for a new bill of rights. He also insisted that the “right to vote must be open to our citizens irrespective of race, color or creed – without tax or artificial restriction of any kind.” And that November, he won re-election to a fourth term with 53.5 percent of the vote, and the Democratic Party, though it lost a seat in the Senate, gained 20 in the House.

Tragically, FDR was right about the dangers of rightist reaction. Americans’ hopes and aspirations were stymied by aggressive and well-funded conservative and corporate campaigns. Still, compelled by popular pressure, Congress did enact a “GI Bill of Rights,” an historic initiative that enabled 12,000,000 veterans – nearly 1 in 10 Americans – to radically transform themselves and their country for the better. And in years to come their generation would not only make America richer and stronger, but would act anew to progressively realize the vision that Roosevelt had projected.

We need to redeem that vision. President Obama has rightly warned that inequality seriously threatens America’s promise. He may not be able to enact any new grand initiatives before he leaves office. But remembering Franklin Roosevelt’s 1944 Message, and speaking with confidence in and to his fellow citizens, he may not only get Americans to vote Democratic in November and set the agenda for 2016. He may also encourage us to go “All Out!” in the fight to renew America’s grand experiment in democracy. That would be a great second-term legacy.

Harvey J. Kaye is Professor of Democracy and Justice Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay and the author of the forthcoming book The Fight for the Four Freedoms: What Made FDR and the Greatest Generation Truly Great (Simon & Schuster). Follow him on Twitter @harveyjkaye

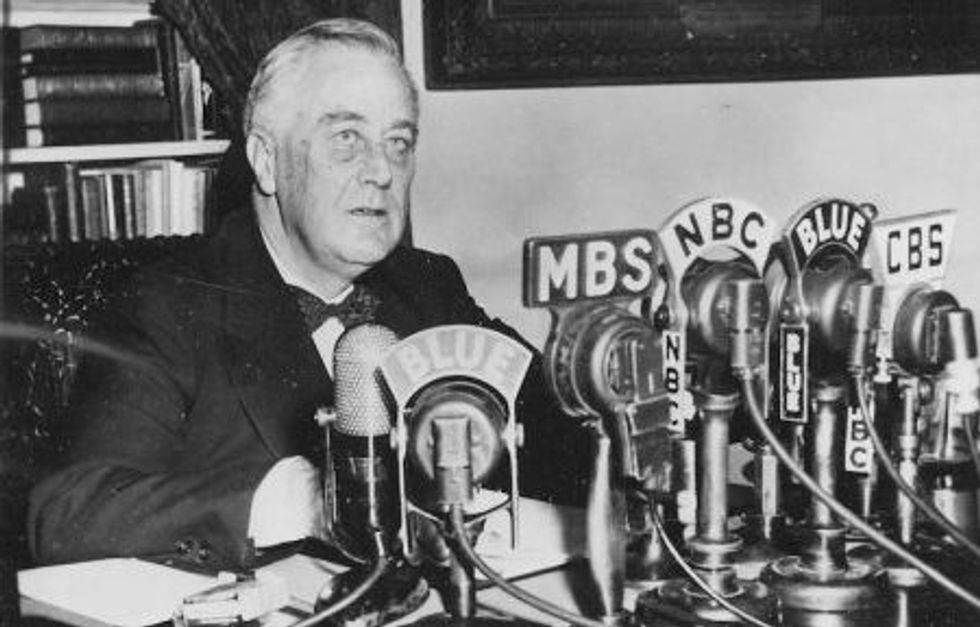

Photo via Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum