Welcome to the sixth part of our ongoing series, examining all the ways that the artistic and entertainment communities have been trying to warn America that Donald Trump (or someone like him) was up to no good.

—

One of the wisest political minds to analyze Donald Trump might actually be sitting in the halls of American government: Sen. Al Franken (D-MN). Why him, you might ask? Because he already wrote the book on Trump’s campaign, nearly 20 years ago.

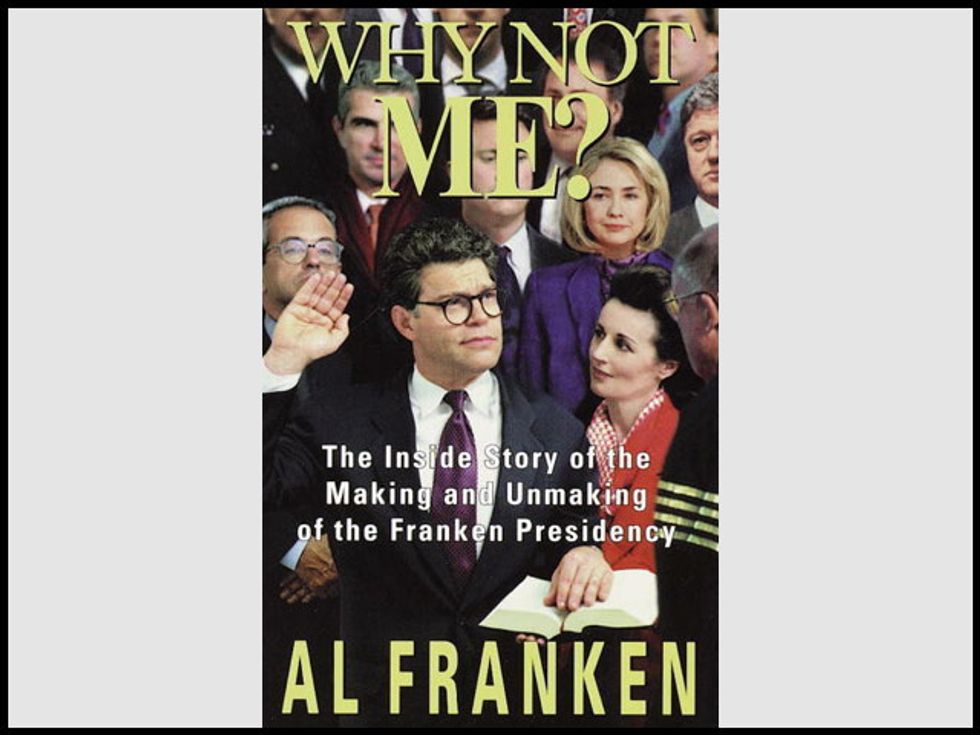

In early 1999, Franken published his novel, Why Not Me? The Inside Story of the Making and Unmaking of the Franken Presidency, a political satire in which his fictional self embarks on a presidential campaign as an obnoxious celebrity candidate.

The media first regard Franken’s campaign as a curiosity. But due to a strange confluence of events, he goes on to become the frontrunner in the race and ultimately wins the Democratic primaries and even the general election in massive landslides.

Sound familiar?

Candidate Franken’s fictional (and highly dishonest) campaign autobiography.

Click images to enlarge.

After actually winning the presidency, however, Franken’s disastrous term lasts only 144 days. In a scene reminiscent of the fall of President Richard Nixon, the Supreme Court rules unanimously that Franken’s personal diary is not protected by executive privilege, and he resigns in disgrace after its contents reveal, in his own words, his criminality and despicable personal character.

The book is made much funnier by the knowledge that, 10 years later, its author successfully pursued an actual career in politics. It should also be noted that Franken’s 2008 competitor, Norm Coleman, seems to have never significantly taken advantage of this novel or used excerpts of it out of context — such as the audiobook version, which was read aloud by Franken himself — a true act of campaign malpractice. One thing is clear, though: Franken forever ruined the timeless sub-genre of political comedians joking about how absurd it would be if they were to actually run for office themselves.

Franken consulted with a variety of political and media experts for the book, most notably his friend Norm Ornstein, resident scholar (and some might argue, the resident sensible liberal) at the American Enterprise Institute.

“It is true that this book has extraordinary relevance today,” Ornstein told The National Memo. “It shows how a bombastic, populist candidate can resonate with a substantial slice of the public, and mesmerize the press. The line between satire and reality is often faint, but in this case it is entirely erased.”

Indeed, this author would like to offer up an idea: If in fact Donald Trump ends up as the Republican nominee, the Clinton campaign would be very well-advised to pair up Sen. Franken (who, as a longtime friend of the Clintons, has endorsed Hillary) as Clinton’s partner in debate-preparation sessions — that is, with Franken channeling his old fictionalized character in order to portray The Donald.

(Also come to think of it, it might even be useful for Franken to help Clinton now, playing Bernie Sanders — but let’s not go too far off on a tangent.)

Franken never actually follows Ornstein’s advice to cease his “very illegal activities.”

The book depicts Franken running a campaign initially based on the single issue of ATM fees — over which, as Ornstein explained, the book’s various consultants all got a big laugh when Bernie Sanders made them an actual issue this year. Franken manages to connect just about any issue, from health care to jobs, to ATMs and the evil banks that charge fees on them — just as Trump launched his campaign on his extravagant promises of an impossible wall that he keeps insisting Mexico will pay for.

Franken’s campaign, however, soon becomes a vehicle for another issue: attacking banks as institutions, and enjoying massive fundraising from their rivals in the insurance industry, taking up their agenda to repeal the final vestiges of the Glass-Steagall regulations so that they can get into banking themselves. (By contrast, in real life Bernie has campaigned vigorously against the past repeal of Glass-Steagall’s separation of commercial and retail banking.) Franken’s fictional campaign thus demonstrates a pitfall of populist campaigns: Demonization of one industry can all too often serve some other industry, and its own robber barons who would stand to benefit from a new wave of government action.

Much of the book is written in the form of a secret diary. After his fictional attorney Joel Kleinbaum tells him to stop keeping it, Franken simply goes on using an obvious code: His wife Franni becomes “F,” the lawyer Joel is “J,” adviser Norm Ornstein is “N,” etc. Throughout the diary, candidate Franken discusses his sexual misadventures, various political frauds and outright crimes committed by his campaign, casual racist and sexist jokes, his worship of himself, and the total pride he takes in everything he does, regardless of its actual value. (One wonderful little passage details Franken’s excitement over a particularly impressive bowel movement.)

But the single biggest theme of the journal is the candidate’s total hatred of the voters among whom he’s campaigning, and his continued amazement at how easy it is to get the “fools” to like him.

From the very first diary entry: “Mud. Also snow. Also people in New Hampshire incredibly stupid. Visited grotesque old lady and man who wanted to talk about Medicare but had lost dentures. Yuck! Think woman will vote for me; man on fence.”

And another: “F organized ‘Farewell, Al’ hayride for local underprivileged youth but told me to stay behind at last minute when I made joke about anyone who lives in N.H. being by definition underprivileged.”

And this doozy: “When I tell J how unbearably dull Iowa seems to me and how I just want to kill myself and everyone in the state every time I look out the car window, he laughs but says he hopes I’m not still keeping diary. I laugh. Also, one other thing I’ve noticed: Iowans are really fat.”

This culminates in a scene where, as told in a fawning Newsweek article, Franken is asked about gun control by a loud rally attendee:

Avoiding a canned, rote response, Franken almost appears to be inventing his policy right there on the spot. To hammer home his opposition to private ownership of semi-automatic assault weapons, Franken pulls a chilling rabbit out of his intellectual hat. “If I had a machine gun, I could kill each and every one of you in just a few seconds,” Franken tells the crowd, which at first lets out a collective gasp, then applauds, and then finally rises to a standing ovation in acknowledgment of the potency of Franken’s graphic hypothetical.

Does this ring a bell?

Back in January, of course, Trump boasted to a rally in Iowa of the sheer loyalty of his voters: “And you know what else they say about my people, the polls? They say I have the most loyal people — did you ever see that, where I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose any voters, okay? It’s like, incredible.”

And just like candidate Franken declaring his genuine desire to shoot people, Trump’s line got a YUGE round of applause. (It was, in fact, this exact moment of Trump on the campaign trail that jogged this author’s memory of Franken’s book, and the stunning resemblances to it that Trump presents.)

Franken also has a severe dislike of Christians, possibly related to anti-Semitism that his character might have encountered as a child in a rural Minnesota town as related in his unreliable campaign autobiography, Daring to Lead. (In real life, Franken grew up in the heavily Jewish Twin Cities suburb of St. Louis Park.)

But even beyond contempt for Christians, he clearly has no concern for any common morality, except so he might please the public. He records in one diary entry: “Prayer breakfast with Gentile clergymen. Must memorize popular Christian prayer: ‘Our Father, etc.'”

A candidate engaging in rote memorization of prayers in order to fool a religious audience, of course, bears a striking resemblance to Trump’s great moment in January at the religious-right institution of Liberty University, when The Donald quoted from that venerable New Testament volume, “Two Corinthians.”

“But it is so true, when you think,” Trump said. “And that’s really — is that the one? Is that the one you like? I think that’s the one you like, ’cause I loved it!”

Franken’s campaign is based heavily around the politics of personal destruction — not too different from Trump’s own alpha-male campaigning approach of tearing his opponents to ribbons. See his attacks on Ben Carson (who has now endorsed him!) or Carly Fiorina (who now supports Ted Cruz) or Jeb Bush (who has disappeared).

But first, Franken has to clear the air on his own misbehavior, as he described in Daring to Lead:

I admit that during the SNL years I caused pain in my marriage. Specifically, the sort of pain that might have been caused if I had been repeatedly unfaithful to my wife and spent a number of holidays and anniversaries away from home in the company of a series of mistresses.

When I decided to run for president, I knew there would come a time when I would have to address this issue. It’s become an unfortunate fact of life that anyone running for president in this day and age must not only present a compelling vision for the future of the country, which is time-consuming enough, but also expose his private life to the closest possible scrutiny.

He then lays out a bizarre set of preconditions for reporters, making it clear that they are not to ask him about any extra-marital affairs — past or present.

But then, just several pages later, as candidate Franken is delivering a vastly exaggerated image of his own accomplishments in public life, presenting himself as a crucial aide to President Bill Clinton, he goes out of his way to throw mud at his main opponent:

Being a White House insider had its shocking and unseemly side. This was brought home to me every time I would encounter Al Gore, whose uncontrollable libido and inappropriate sexual behavior toward anything with two legs and a hole in between brought shame and ill-repute to Bill Clinton’s presidency

Gore’s one-track mind afforded little room for contemplation of issues not related to his dick. I remember Gore leaving a meeting to go chase girls after a particularly unimpressive performance. I turned to Panetta, rolled my eyes, and asked, “Is it just me? Or is that guy a complete zero?” Panetta confirmed my worst suspicions about the vice president, saying something to the effect that putting him on the ticket had been a mistake.

And of course, Trump is an unlikely figure to lob moral attacks at others, having boasted in the past that his sexual escapades while avoiding STD infections were “my personal Vietnam. I feel like a great and very brave solider.” And let’s not even get into the jokes he’s kept on making about his own daughter.

But let’s get back to one of Franken’s primary methods of running against Gore: Vicious personal attacks, and behavior so outlandish that the staid, traditional Gore simply never has any idea how to respond. As an example, Gore is followed around by Al Franken’s fictional brother Otto Franken, a violent and vulgar drunk who systematically challenges Gore’s honesty and basic humanity.

Can you imagine that: Al Gore getting done in by a campaign full of lies and simplistic emotional attacks, rendering useless any calm and factual response?

Otto also engages in multiple criminal activities, from running a meth lab and laundering money to the campaign from a phone-sex line, to assaulting pesky reporters and rival campaign staff with his weapon of choice, a wooden board — and if this sounds too outlandish, just look at Trump’s suspicious campaign finances and his active fomenting of violence against protesters.

Franken also cultivates media friendships, a process that finally results in Howard Fineman’s fawning news article for Franken as the campaign heads towards two crucial events: Franken nearing victory in the race for the presidency (after the “Y2K” bug wipes out everybody’s bank accounts) and Fineman joining the Franken campaign as its new press secretary, after being paid off for his silence before he uncovers the truth about Franken’s various acts of skullduggery.

The article shows the fashion in which a politician can manipulate the media/politics revolving door, constructing an elaborate fraud and a personality that encourages the public to fall in love and see what they want to see.

So what happens when he actually does win the presidency in a historic landslide? Like the dog who finally catches the firetruck, Franken is stunned upon taking office at the awesome responsibilities he has just taken upon himself — and promptly has a mental breakdown, as catalogued in a fictional book-within-the-book supposedly authored by Bob Woodward.

When his inaugural address goes horribly awry, the new president hides himself in the Lincoln bedroom, surrounding himself with all the newspapers’ terrible reviews. As First Lady Franni Franken explains to Chief of Staff Norm Ornstein, “It was like this after his Stuart Smalley movie bombed.”

One can certainly find a parallel in Trump’s obsession with his own news coverage, with the polls — and his very negative response to his loss in the Iowa Caucuses, as he insisted that Ted Cruz’s dirty tricks to win it were so heinous that the election should be overturned.

After an examination by a doctor for depression, the White House team decides to lie to the public, and say that President Franken is actually suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome as a result of the Epstein-Barr virus — that’s right, the president had become “low energy.”

But even this is only the beginning of their troubles, as Franken is actually misdiagnosed: He isn’t suffering from depression. He’s bipolar, and the initial treatments only increase his manic behavior: Punching former South African President Nelson Mandela, scheming to personally bludgeon Saddam Hussein to death, and finally having himself cloned.

To be fair, Trump hasn’t exactly done any of that stuff — not yet, anyway.

—

This is the sixth in our series “Pop Culture Warned Us About Trump.”

Check out Part 1: “The Penguin”; Part 2: “MAD Magazine”; Part 3: Lex Luthor; and Part 4: ‘The Dead Zone’; and Part 5: ‘The Waldo Moment.’