Of all the consequences of the nation’s decades-long infatuation with building more and more prisons and locking up more and more citizens, perhaps the most curious is this: More than 4 million Americans who have been released from prison have lost their right to vote, according to the non-profit Sentencing Project.

Even after men and women have served their time — after they have paid their debt to society, as the cliche goes — most states restrict their franchise. It’s an odd idea: Those men and women are harmless enough to release onto the streets, but they can’t be trusted to vote. They have finished serving their sentences, but they are barred from full citizenship.

A disproportionate number of those second-class citizens are black. Because black Americans, particularly men, are locked up at a higher rate than their white peers, this peculiar practice falls heavily on them. Nationwide, one in every 13 black adults cannot vote as the result of a felony conviction, as opposed to one in 56 non-black voters, according to the Sentencing Project, which advocates for alternatives to mass incarceration.

It’s undemocratic, it’s unfair and it’s un-American. While ancient Greek and Roman codes withdrew the franchise from those who had committed serious crimes, most Western countries now see those codes as outdated.

Recognizing that, Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, used his executive power earlier this month to sweep away his state’s laws limiting the franchise for felons. With that action, about 200,000 convicted felons who have completed their prison time and finished parole or probation are now eligible to vote.

McAuliffe noted that Virginia’s law — one of the nation’s harshest and embedded in a Civil War-era state constitution — didn’t hobble the voting rights of black citizens through mere coincidence. That was its purpose. McAuliffe’s staff came across a 1906 report in which a then-state senator gloated about several voting restrictions, including a poll tax and literacy tests, that, he said, would “eliminate the darkey as a political factor in this state in less than five years,” according to The New York Times.

You’d think that McAuliffe’s fellow Virginia politicians, Republicans and Democrats alike, would celebrate his decision. Eliminating barriers to the franchise — especially those with obviously racist roots — can only polish the state’s image and strengthen the civic fabric.

But GOP leaders have objected, accusing McAuliffe of “political opportunism” and a “transparent effort to win votes.” Well, OK. Let’s stipulate that politicians are usually in the business of trying to win votes.

Having conceded that, though, isn’t restoring the voting rights of men and women who have served their time a good idea? If a crime renders a man beyond the boundaries of civilized society, he should be imprisoned for the rest of his life. Otherwise, his crime shouldn’t place him in an inferior caste, without the privileges of full citizenship.

Curiously, though, many conservatives seem to disagree. After Democrat Steve Beshear, then Kentucky’s governor, issued an executive order last year similar to McAuliffe’s, his Republican successor, Matt Bevin, overturned it. Bevin signed a law allowing felons to petition judges to vacate their convictions — a bureaucratic hurdle not easily overcome. Maryland’s GOP governor, Larry Hogan, vetoed a bill to restore voting rights to felons, but the Democratically controlled legislature overrode him.

Those Republican governors are simply following the party’s script, which has focused for the last several years on ways to block the ballot, starting with harsh voter ID laws. While advocates of such laws claim they are meant to protect against voting fraud, the sort of in-person fraud they would prevent hardly exists.

The real motivation for GOP lawmakers is to restrict the franchise from people unlikely to vote for them — especially people of color and millennials. Rather than campaign on a platform that attracts support, they rely on barriers to voting.

That’s wrong. The strength of American democracy depends on persuading more citizens that their votes count; carelessly — or intentionally — disenfranchising those with whom you disagree rends the civic fabric, distorts the political process and stokes the flames of discontent.

We surely don’t need more of that in this political season.

Cynthia Tucker won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 2007. She can be reached at cynthia@cynthiatucker.com.

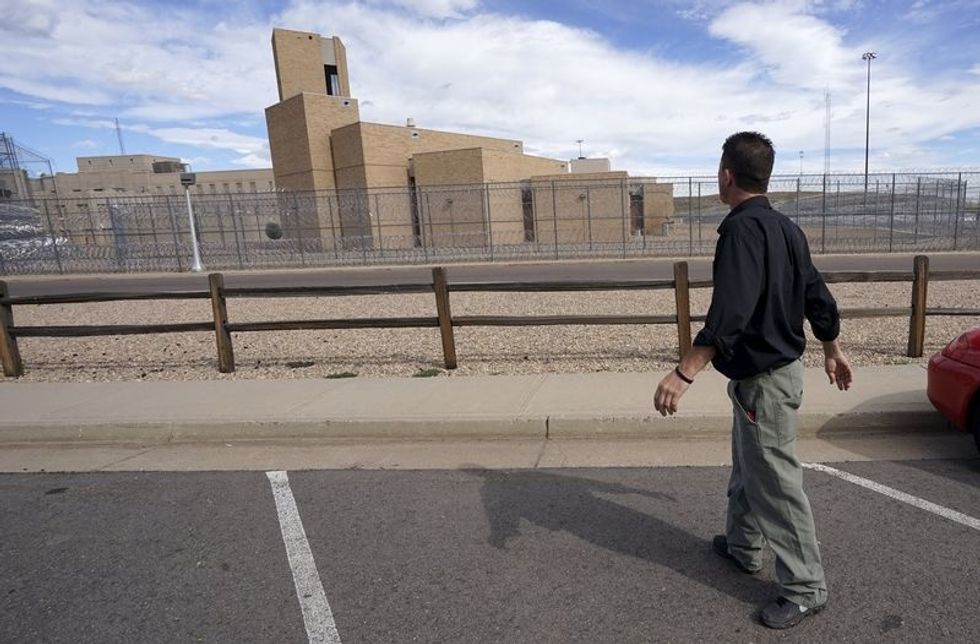

Photo: Peer 1 client James J. looks at the federal prison during a blind faith trust exercise in Englewood, Colorado September 15, 2015. REUTERS/Rick Wilking