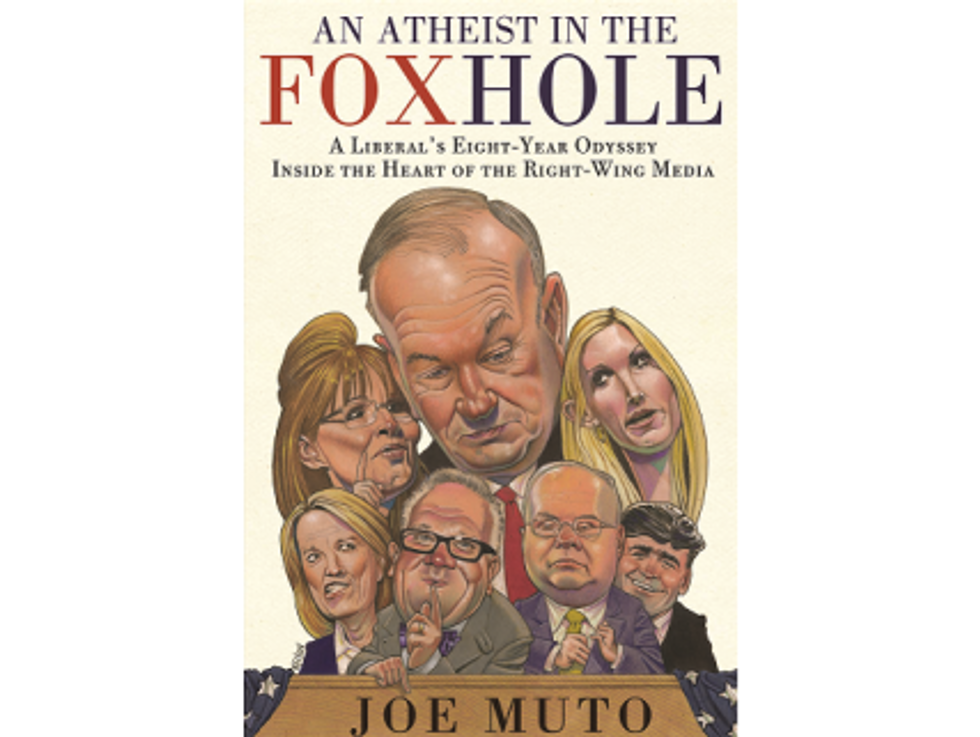

Weekend Reader: An Atheist In The FOXhole: A Liberal’s Eight-Year Odyssey Inside The Heart Of The Right-Wing Media

This week, Weekend Reader brings you an excerpt from Joe Muto’s recently released book, An Atheist in the FOXhole. Muto went “undercover” in the world of mainstream conservative media, gaining access to the kingpin of them all. Working under Roger Ailes and Bill O’Reilly at Fox News turned out to be an eye-opening experience for Muto — he was there to research and tell a story, but keeping his personal beliefs hidden in a job he came to detest was no easy task. In Muto’s fascinating and enlightening book he details the power dynamics within the Fox News network — full of scare tactics, paranoia, and intimidation from the ultra-conservative power elite at Fox News.

You can purchase the book here.

People would often ask me about how Fox pushes a message.

And I would always tell them the message isn’t so much pushed as it is pulled, gravitationally, with Roger Ailes as the sun at the center of the solar system; his vice presidents were the forces of gravity that kept the planet-size anchors and executive producers in a tight orbit; then all the lesser producers and Pas were moons and satellites and debris of varying sizes.

An organizational flow chart at Fox would be tough to draw up, as title alone was not the ultimate signifier of status. Sometimes the anchors outranked their executive producers, as was the case with The O’Reilly Factor. (In fact, Bill had procured an EP title for himself, but he outranked the two other EPs on the show, both Stan, who oversaw TV, radio, and the website, and Gayle, who focused on television and also served as a fact-checker.) Sometimes the anchors were relatively weak—as was the case with a lot of weekend shows, and maybe some of the newswheel hours—and a strong senior producer or producer outranked, or at least pretended to outrank, the host. (For example, Lizzie from The Lineup, who was only a producer but was tough enough that she probably could have bossed around Ailes himself had she been left alone in a room with him for more than five minutes.)

The bottom line is that each show had one person—be they anchor or producer or whoever—who was directly accountable to the Second Floor. That was the brilliance of the company’s power structure. One misconception that outsiders always had about the channel is that we’d sit around all morning planning how to distort the news that day. But there was never any centralized control like that. No “marching orders,” as it were. Instead, it was more a decentralized, entrepreneurial approach. Each show was an autonomous unit. Each showrunner—who had no risen to their position by being stupid—knew exactly what was expected of them, knew what topics and guests would be acceptable.

Theoretically, each show could talk about whatever they wanted to talk about, and take any angle they wanted to take, and book any guest they wanted to have on.

Realistically, there was tremendous pressure to hew closely to the company line. The Second Floor monitored the content of every show very closely. Each show was required to submit a list of all the guests and all the topics well before the fact; the list would be reviewed by one of the relevant vice presidents. Most of the time, this was just a formality—as I said, the showrunners knew their boundaries—but every once in a while, a certain guest or topic would set off alarm bells on the second floor, leading to a series of increasingly urgent and unpleasant e-mails and phone calls for the showrunner.

Even if a segment passed initial muster, the Second Floor reserved the right to pull the plug if it took a turn they didn’t like. They were always watching, and never hesitant to exercise their authority. Roger himself had a phone in his office, a hotline he could pick up and immediately be connected to the control room. Every producer knew that, and dreaded seeing his name on the caller ID. If Roger took the time to personally call the control room, in my experience it was almost never complimentary.

It was a unique, bottom-up management structure that had built-in checks and balances coming from the top down. This approach had its advantages and disadvantages. On the upside, it often led to innovative programming, with adventurous hosts and producers coming up with story ideas and segments that a more buttoned-down, dictatorial management structure might otherwise never have approved. (O’Reilly was one of the beneficiaries of this, successfully experimenting with some of his more outlandish, barely news-related segments like Body Language and the Quiz.)

One of the disadvantages was that the Second Floor often put insane, arbitrary restrictions into place, with networkwide implications.

For example, some unlucky guests were banned for life from every show on the network, a result of a diktat from the Second Floor. Comedian Bill Maher, once a semi-regular guest on The Factor and some other Fox shows, made too many cracks about Sarah Palin over the years, raising the ire of a powerful female VP who banned him from our air and demanded that all Fox-affiliated websites refer to him only as “Pig Maher.”

Sometimes entire organizations were given lifetime bans. The website Politico wrote something a few years back that rubbed Roger the wrong way (we were never told what exactly the transgression was) and word went out to all the shows: No more Politico reporters as guests. Also any anchors who mentioned the site on air had to use the phrase “left-wing Politico”—an absurd designation for a publication that usually played it down the middle.

Some anchors and producers had enough juice—proportional to the size of their audience, generally—to push back against the Second Floor’s mandates, with varying levels of success, though even O’Reilly, who had more juice than anyone, could only do so much. When one of his favorite guests, a fiery, young, liberal African American college professor, was banned, Bill lobbied on his behalf, eventually striking an agreement with the Second Floor allowing him to continue to use the guy as long as his appearances were limited to once a month. O’Reilly wasn’t happy with it, but it was better than walking away empty-handed.

There was nothing Bill hated more than management impositions on his show. These impositions almost always followed the same pattern—Stan would get a phone call in his office from one of Roger’s underlings, usually a vice president named Bill Shine. I’d hear Manskoff’s end of the conversation. “You’re killing me here, you know that, don’t you,” Stan would say. “You know he’s going to hate this.” Manskoff would hang up, shaking his head in disbelief, and make the fifteen-foot trek to Bill’s office, closing the door behind him. Through the door, we’d hear muffled talking from Stan, then muffled shouting from Bill, followed shortly by the door popping open and Stan bolting from the office like a pinball from a launcher.

© 2013 by Joseph Muto. Reprinted with permission of Dutton, member of Penguin Group USA.