In a February op-ed published in The New York Times, Oliver Sacks, the eminent neurologist and cultural luminary, revealed to the world that he was dying of terminal cancer.

Sacks discussed his new resolve to live life free of inessentials, and his gratefulness for being able to participate in what he called “the special intercourse of writers and readers.” It’s a relationship that Sacks has built and maintained over the decades through his myriad essays and books, such asAwakeningsandThe Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat, which meld his extensive knowledge of the biology of the brain with a generous, inquiring spirit, and shine a light on what he dubbed “the suffering, afflicted, fighting human subject.”

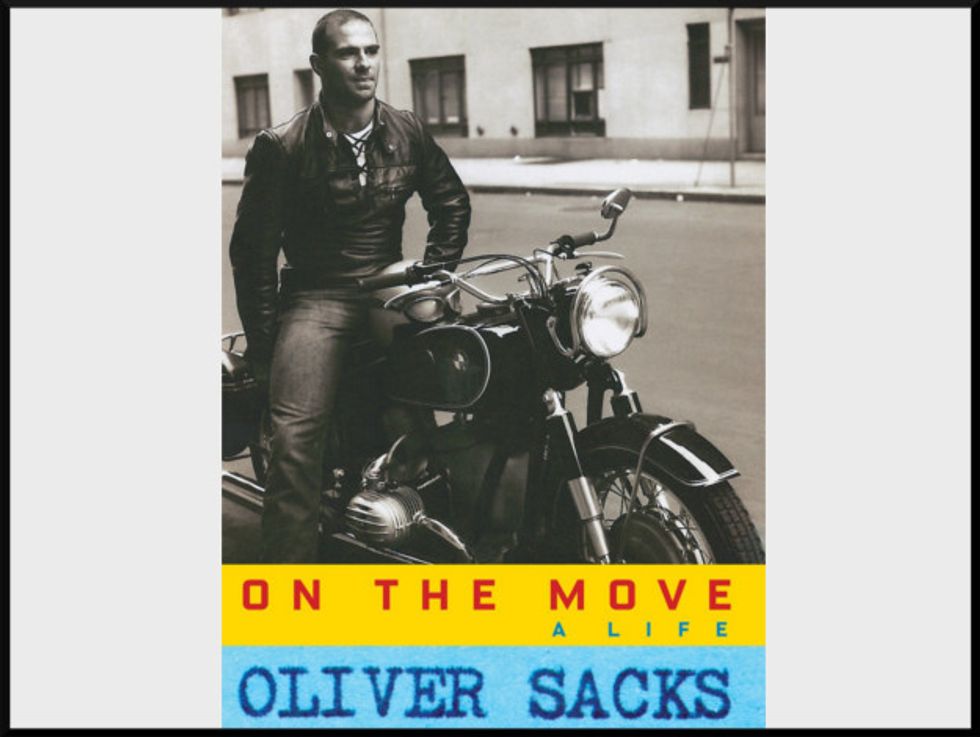

In his latest book, On the Move: A Life, the “human subject” is Sacks himself. Picking up where his previous memoir, Uncle Tungsten, left off, On the Moveis a chronicle of unmoored youth, capturing young Sacks’ detours, setbacks, and flashes of early brilliant discovery.

You can read an excerpt below. The book is available for purchase here.

—

Muscle Beach

When I finally made it to New York in June of 1961, I borrowed money from a cousin and bought a new bike, a BMW R60 — the trustiest of all the BMW models. I wanted no more to do with used bikes, like the R69 which some idiot or criminal had fitted with the wrong pistons, the pistons that had seized up in Alabama.

I spent a few days in New York, and then the open road beckoned me. I covered thousands of miles in my slow, erratic return to California. The roads were wonderfully empty, and going across South Dakota and Wyoming, I would scarcely see another soul for hours. The silence of the bike, the effortlessness of riding, lent a magical, dreamlike quality to my motion.

There is a direct union of oneself with a motorcycle, for it is so geared to one’s proprioception, one’s movements and postures, that it responds almost like part of one’s own body. Bike and rider become a single, indivisible entity; it is very much like riding a horse. A car cannot become part of one in quite the same way.

I arrived back in San Francisco at the end of June, just in time to exchange my bike leathers for the white coat of an intern in Mount Zion Hospital.

During my long road trip, with snatched meals here and there, I had lost weight, but I had also worked out when possible at gyms, so I was in trim shape, under two hundred pounds, when I showed off my new bike and my new body in New York in June. But when I returned to San Francisco, I decided to “bulk up” (as weight lifters say) and have a go at a weight- lifting record, one which I thought might be just within my reach. Putting on weight was particularly easy to do at Mount Zion, because its coffee shop offered double cheeseburgers and huge milk shakes, and these were free to residents and interns. Rationing myself to five double cheeseburgers and half a dozen milkshakes per evening and training hard, I bulked up swiftly, moving from the mid-heavy category (up to 198 pounds) to the heavy (up to 240 pounds) to the superheavy (no limit). I told my parents about this — as I told them almost everything — and they were a bit disturbed, which surprised me, because my father was no lightweight and weighed around 250 himself.

I had done some weight lifting as a medical student in London in the 1950s. I belonged to a Jewish sports club, the Maccabi, and we would have power-lifting contests with other sports clubs, the three competition lifts being the curl, the bench press, and the squat, or deep knee bend.

Very different from these were the three Olympic lifts — the press, the snatch, and the clean and jerk — and here we had world-class lifters in our little gym. One of them, Ben Helfgott, had captained the British weight-lifting team in the 1956 Olympic Games. He became a good friend (and even now, in his eighties, he is still extraordinarily strong and agile). I tried the Olympic lifts, but I was too clumsy. My snatches, in particular, were dangerous to those around me, and I was told in no uncertain terms to get off the Olympic lifting platform and go back to power lifting.

The Central YMCA in San Francisco had particularly good weight-lifting facilities. The first time I went there, my eye was caught by a bench-press bar loaded with nearly 400 pounds. No one at the Maccabi could bench-press anything like this, and when I looked around, I saw no one in the Y who looked up to such a weight. No one, at least, until a short but hugely broad and thick-chested man, a white-haired gorilla, hobbled into the gym — he was slightly bowlegged — lay down on the bench, and, by way of warmup, did a dozen easy reps with the bench-press bar. He added weights for subsequent sets, going to nearly 500 pounds. I had a Polaroid camera with me and took a picture as he rested between sets. I got talking to him later; he was very genial. He told me that his name was Karl Norberg, that he was Swedish, that he had worked all his life as a longshoreman, and that he was now seventy years old. His phenomenal strength had come to him naturally; his only exercise had been hefting boxes and barrels at the docks, often one on each shoulder, boxes and barrels which no “normal” person could even lift off the ground.

I felt inspired by Karl and determined to lift greater poundages myself, to work on the one lift I was already fairly good at — the squat. Training intensively, even obsessively, at a small gym in San Rafael, I worked up to doing five sets of five reps with 555 pounds every fifth day. The symmetry of this pleased me but caused amusement at the gym — “Sacks and his fives.” I didn’t realize how exceptional this was until another lifter encouraged me to have a go at the California squat record. I did so, diffidently, and to my delight was able to set a new record, a squat with a 600-pound bar on my shoulders. This was to serve as my introduction to the power-lifting world; a weight-lifting record is equivalent, in these circles, to publishing a scientific paper or a book in academia.

Excerpted from On The Move by Oliver Sacks. Copyright © 2015 by Oliver Sacks. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our email newsletter!