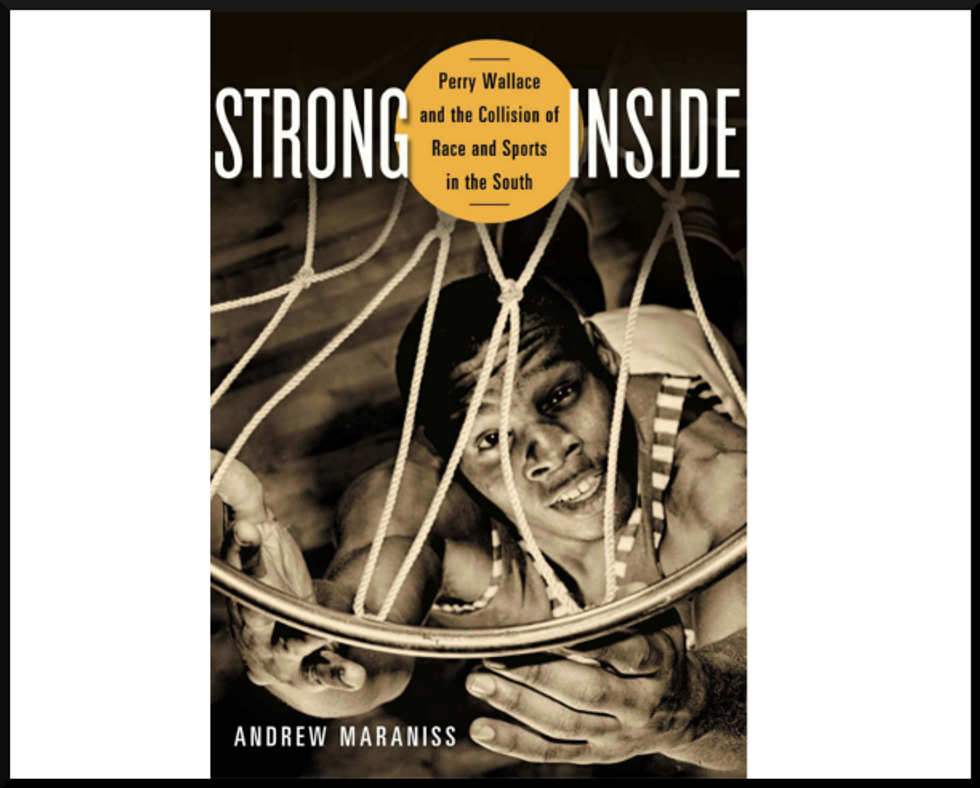

Weekend Reader: ‘Strong Inside: Perry Wallace And The Collision Of Race And Sports In The South’

When Vanderbilt University recruited Perry Wallace in 1965, he was to be the first African-American scholarship basketball player in the Southeastern Conference. It wasn’t easy. His experience is the subject of Andrew Maraniss’ new book, Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South.

A richly detailed, intimate account of the experiences of Wallace and the generation of African-American students who blazed the trail for integrated higher education, Maraniss’ history explores how, under the tidal force of integration, people endured mundane cruelty and everyday ignorance. Not merely the story of triumph we’ve come to expect from the genre, Strong Inside tells a more complex story, and paints an honest, penetrating portrait of what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called “the agonizing loneliness of a pioneer.”

In the following excerpt, Maraniss introduces Eileen Carpenter, one of Wallace’s contemporaries, and another of the first African-American students at Vanderbilt. “I thought that since Vanderbilt had opened, it was open,” she later recalled. “After our parents had struggled through the real fight, the physical and the name calling and the killing and the lynchings, I think it set my generation up for expecting movement to another level. We actually expected community.”

You can purchase the book here.

For Eileen Carpenter, who grew up in an upper-middle-class black family in Nashville, the crash came gradually, and at first she couldn’t put her finger on what was happening. In the summer following her senior year of high school, a puzzling pattern repeated itself when she attended parties for incoming Vanderbilt freshmen.

Carpenter arrived at the parties, held in the homes of wealthy alums, excited and happy, only to find herself standing alone with her plate of food while others in the room laughed and talked as if they all knew each other. “People were not mean or anything, and if they caught your eye, they’d smile, but I started having this sense that I was just kind of there, just being politely ignored,” she recalled. “At the time, it did not occur to me that maybe it was because I was black. I was making mental notes, but things weren’t clicking.”

It wasn’t until Carpenter sat alone in the Rand Hall dining room that everything began to click. A cat darted through the cafeteria, but nobody seemed to notice. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘I’m just like that cat. I don’t make any difference.’ Nobody paid any attention. Nobody looked up. It was then that I started understanding what I was feeling and what was going on. It was Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. You were not there. You didn’t impact anyone’s life. You could be totally ignored, and if you disappeared, nobody would notice.” Frustrated by these experiences, Carpenter would come home from school, throw her books in the corner of her room, and crawl into bed. “My parents couldn’t understand,” she recalled, “because nobody was being mean to me.”

These periods of isolation only told half the story. When not completely ignored, many black students felt that they were on the receiving end of piercing stares from their white classmates. They could experience both extremes in a matter of minutes, creating a chronic self-consciousness that made even the most mundane of activities unpleasant. Perry Wallace accompanied a small group of white classmates to dinner one evening in the cafeteria at the women’s quadrangle. As he waited in line to choose his food, he looked up and realized that every pair of female eyes in the room was focused right on him, the coeds’ pinched faces betraying feelings of fear, hatred, or maybe both, he couldn’t be sure. Wallace’s mother had warned him to “stay away from the white girls,” and now, before he could even take a bite to eat, it seemed to him that the smartest solution might be to just leave the room.

![]()

Whether it was naïveté or just the fact that they hadn’t really thought about it before arriving at Vanderbilt, the degree of seclusion they felt on campus initially came as a surprise to the black students. They would do the best they could to make the most of their days at Vanderbilt, but they would also seek alternative social outlets. While the grand social experiment of integration might take decades to sort itself out, these students only had one college experience, just four years to determine what worked best for them as individuals.

For some, this meant approaching student life at face value—attempting to do the same things white students took for granted. Unaware that none of the Vanderbilt sororities admitted blacks, Carpenter arrived on campus thinking she was going to “have a great time and join a sorority like the college days you saw on TV.” She walked past all the sorority houses and picked the one she liked best—Kappa Alpha Theta. Carpenter attended the sorority’s first rush party. Everything seemed to be going just fine, and when Carpenter’s aunt came to visit one day, Eileen told her all about her plans to join the sorority. “She looked at me like my head had just dropped off my body,” Carpenter recalled. “She said, ‘You can’t join a sorority there, they won’t allow Negroes.’ I couldn’t quite believe her, so I called (a member), and I immediately knew by the way she started sputtering that it was true.”

Bedford Waters joined the men’s residence hall executive board and eventually becoming the organization’s first black president— a feat that earned him ridicule, not so much from whites but from blacks who accused him of selling out. Waters felt he was constantly engaged in a game of tug-of-war, trying his best to enjoy his college experience by participating in the pursuits that interested him, all while catching hell from some whites who didn’t want him around and some blacks who thought he was betraying them. “You want to be accepted among all your peers, but there was this perception that if you’re doing anything outside of what was considered to be the norm for African Americans at the time, that you were being disloyal and you were trying to act white,” Waters recalled. “How the hell do you come out of that with some kind of sanity? Obviously I did, but it was a very, very difficult time.”

Perry Wallace has long remembered those early days at Vanderbilt, when black and white students were inelegantly trying to figure each other out—succeeding and failing, improvising, accepting and rejecting. Two worldviews were colliding, he said, one that saw society advancing by placing its trust in movements and causes and legislation, the other rejecting such things, believing that what really mattered were one-on-one relationships. In the end, Wallace concluded, both ideologies were necessary. Without the civil rights movement, much progress would not have taken place. But even with a strong movement, what ultimately mattered to the people living through it were their daily interactions and experiences with individual human beings. Integration was a new exercise for everybody, black and white. “People talked about, ‘Let’s all come together and we’ll all get along.’ Nope, we had too much practice not getting along,” Wallace says. “A lot of us blacks had to practice not feeling inferior after all of that segregation bull. There were a lot of whites who had to practice not feeling superior. We had a chance to practice at Vanderbilt, and some of us did.”

Segregation doesn’t need any extra condemnation, Wallace says. Its evils speak for themselves. There’s a certain level of decency everyone should be afforded. But look at who was being ignored at Vanderbilt in 1966: the best and brightest black students from North and South, the class presidents, the valedictorians, the salutatorians. “Just think about the stories we had to tell,” Wallace said. “The students on campus who rejected us, who ignored us, who isolated us—we brought the opportunity for them to ‘practice being equal.’ The irony is that we were just who they needed to know. We brought with us insights into the world that they lived in that they did not have because segregation had set people apart. We had the other half of the story about race. And we were articulate messengers.”

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Excerpt from Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South by Andrew Maraniss. Copyright © 2014 by the author and reprinted by permission of Vanderbilt University Press.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our daily email newsletter here!