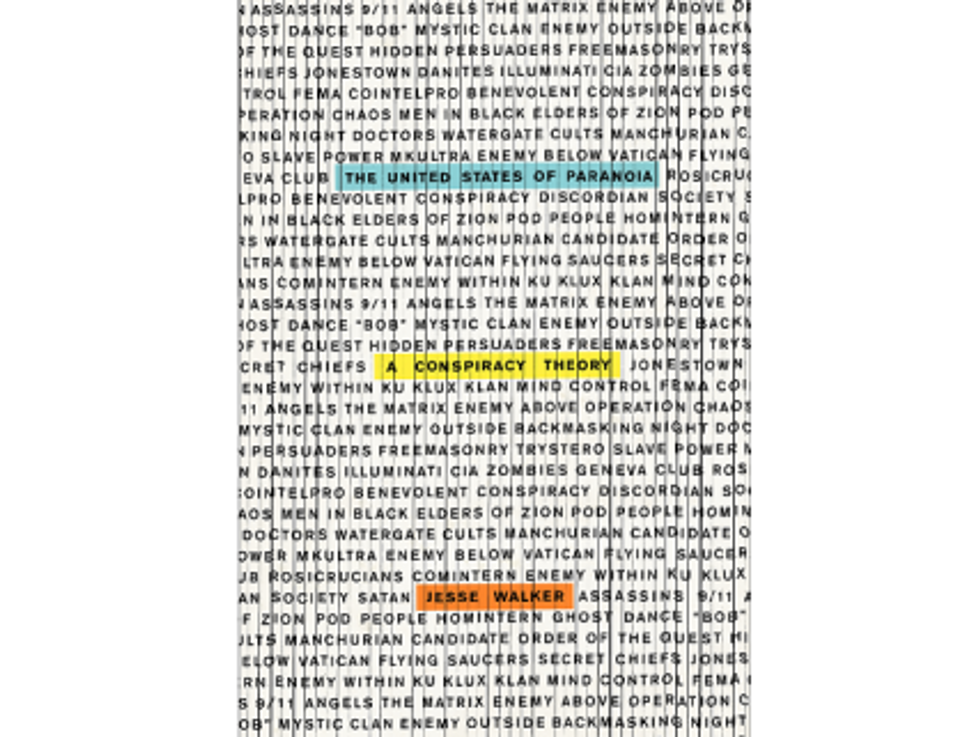

This weekend, The Weekend Reader brings you The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory by Jesse Walker. Released this week, The United States of Paranoia is already ranked on Amazon.com by their editors as one of the top non-fiction books of the month. Walker, a senior editor for Reason who has written extensively on conspiracy theories, challenges the idea of historian Richard Hofstadter that conspiracies begin with and are sustained by marginal groups. Walker argues that many conspiracy theories have gained traction with the help of the politically elite — from the attempted assassination of Andrew Jackson, to JFK’s assassination, to 9/11 — these theories were never limited to groups on the periphery of the U.S., but instead were often sanctioned by the media and political leaders.

Whether we call it a scandal or a conspiracy, we’ve seen no shortage of outrageous claims launched at the Obama administration. But neither side, be they liberal or conservative, is innocent — everyone has contributed to instilling conspiratorial fear at some point in time. In The United States of Paranoia Walker details a list of conspiracies throughout history; his aim is not to to unmask the truth behind any theories, but instead highlight their repercussions and explain why conspiracy theories will just never go away.

You can purchase the book here.

Pundits tend to write off political paranoia as a feature of the fringe, a disorder that occasionally flares up until the sober center can put out the flames. They’re wrong. The fear of conspiracies has been a potent force across the political spectrum, from the colonial era to the present, in the establishment as well as at the extremes. Conspiracy theories played major roles in conflicts from the Indian wars of the seventeenth century to the labor battles of the Gilded Age, from the Civil War to the Cold War, from the American Revolution to the War on Terror. They have flourished not just in times of great division but in eras of relative comity. They have been popular not just with dissenters and nonconformists but with individuals and institutions at the center of power. They are not simply a colorful historical byway. They are at the country’s core.

Unfortunately, much of the public perception of political paranoia seems frozen in 1964, when the historian Richard Hofstadter published “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Hofstadter set out to describe a “style of mind” marked by “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy,” detecting it in movements ranging from the anti-Masonic and anti-Catholic crusades of the nineteenth century to the “popular left-wing press” and “contemporary right wing” of his time. A flawed but fascinating essay, “The Paranoid Style” is still quoted frequently today. Half a century of scholarship has built on, rebutted, or otherwise amended Hofstadter’s ideas, but that work rarely gets the attention that “The Paranoid Style” does.

That’s too bad. The essay does contain some real insights, and if nothing else it can remind readers that conspiracy theories are not a recent invention. But it also declares that political paranoia is “the preferred style only of minority movements”—and, just to marginalize that minority some more, that it has “a greater affinity for bad causes than good.” In an earlier version of his article, Hofstadter went further, claiming that the paranoid style usually affects only a “modest minority of the population,” even if, under certain circumstances, it “can more readily be built into mass movements or political parties.”

Hofstadter did not provide numbers to back up those conclusions. We do have some data on the popularity of well-known conspiracy theories, though, and the results do not support his sweeping claims. In 2006, a nationwide Scripps Howard survey indicated that 36 percent of the people polled—a minority but hardly a modest one—believed it “very” or “somewhat” likely that U.S. leaders had either allowed 9/11 to happen or actively plotted the attacks. Theories about JFK’s assassination aren’t a minority taste at all: Forty years after John F. Kennedy was shot, an ABC News poll showed 70 percent of the country believing a conspiracy was behind the president’s death. (In 1983, the number of believers was an even higher 80 percent.) A 1996 Gallup Poll had 71 percent of the country thinking that the government is hiding something about UFOs.

To be sure, there is more to Hofstadter’s paranoid style than a mere belief in a conspiracy theory. And there’s a risk of reading too much into those answers: You can believe the government has covered up information related to UFOs without believing it’s hiding alien bodies in New Mexico. (You might, for example, think that some UFO witnesses encountered weapons tests that the government would prefer not to acknowledge.) There is also a revised version of Hofstadter’s argument that you sometimes hear, one that accepts that conspiracies are more popular than the historian suggested but that still draws a line between the paranoia of the disreputable fringes and the sobriety of the educated establishment. It’s just that the “fringe,” in this telling, turns out to be larger than the word implies.

But educated elites have conspiracy theories too. By that I do not mean that members of the establishment sometimes embrace a disreputable theory—though that does happen. When White House deputy counsel Vince Foster turned up dead during Bill Clinton’s term in office, sparking an assortment of conspiracy tales, former president Richard Nixon told his personal assistant that the “Foster suicide smells to high heaven.” Clinton himself, on being elected, asked his old friend and future aide Webster Hubbell, “Hubb, if I put you over at Justice, I want you to find the answers to two questions for me. One, Who killed JFK? And two, Are there UFOs?” But I mean something far broader than that. You wouldn’t guess it from reading “The Paranoid Style,” but the center sometimes embraces en masse ideas that are no less paranoid than the views of the fringe.

Consider the phenomenon of the moral panic, a time when fear and hysteria are magnified, distorted, and perhaps even created by influential social institutions. Though he didn’t coin the phrase, the sociologist Stanley Cohen was the first to use it systematically, sketching the standard progression of a moral panic in 1972: “A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media; the moral barricades are manned by editors, bishops, politicians and other right-thinking people; socially accredited experts pronounce their diagnoses and solutions; ways of coping are evolved or (more often)resorted to; the condition then disappears, submerges or deteriorates and becomes more visible.” To illustrate the idea, Cohen examined the uproar over two teen subcultures of early 1960s Britain, the rockers and the mods, and their sometimes violent rivalry. In press accounts of the time, seaside towns were destroyed by warring gangs, with pitched battles fought in the streets. But the kids had actually stuck to insults and minor vandalism until the media trumpeted their distorted account, inspiring an intense public concern, an increased police presence, and, ironically, a new willingness among the mods and rockers to behave the way they’d been described.

An essential feature of a moral panic is a folk devil, a figure the sociologist Erich Goode has defined as “an evil agent responsible for the threatening condition”—typically a scapegoat who is not, in fact, responsible for the threat. The folk devil often takes the form of a conspiracy: a Satanic cult, a powerful gang, a backwoods militia, a white-slavery ring. (In the case of the rockers and mods, Cohen writes, the press sometimes claimed that their battles “were masterminded, perhaps by a super gang.”) Cohen’s case study is British, but there are plenty of American equivalents. One is the antiprostitution panic of the early twentieth century, which featured lurid talks of a vast international white-slavery syndicate conscripting thousands of innocent girls each year into sexual service. An influential book by a former Chicago prosecutor claimed, in the space of three paragraphs, that the syndicate amounted to an “invisible government,” a “hidden hand,” and a “secret power,” and that “behind our city and state governments there is an unseen power which controls them.”

Coerced prostitution really did exit, but it was neither as prevalent nor as organized as the era’s wild rhetoric suggested. Yet far from being consigned to a marginal minority movement, the scare led to a major piece of national legislation, the Mann Act of 1910, and gave the first major boost in power to the agency that would later be known as the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Within a decade, the Bureau would be extending its purview from alleged conspiracies of pimps to alleged conspiracies of Communists, getting another boost in power in the process.

Such stories are missing from Hofstadter’s account, which drew almost all of its examples from movement opposed to the “right-thinking people” Cohen described. The result was a distorted picture in which the country’s outsiders are possessed by fear and its establishment usually is not. The essay had room, for example, for “Greenback and Populist writers who constructed a great conspiracy of international bankers,” but it said nothing about the elites of the era who perceived Populism as the product of a conspiracy. Hofstadter did not mention the assistant secretary of agriculture, Charles W. Dabney, who denounced William Jennings Bryan’s Populist-endorsed presidential campaign of 1896 as a “cunningly devised and powerfully organized cabal.” Nor did he cite the respectable Republican paper that reacted to the rise of the Union Labor Party, a proto-Populist group, with a series of bizarre exposés claiming that an anarchist secret society controlled the party. “We have in our midst a secret band who are pledged on oath to ‘sacrifice their bodies to the just vengeance of their comrades’ should they fail to obey the commands or keep the secrets of the order,” warned one article in 1888. “How shall we maintain our honored form of government, or protect life and property from assassination at the hands of these conspirators, if their dark and damning deeds are allowed to continue and be perfected?” asked another. The paper kept up the drumbeat till election day.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, you can purchase the full book here.

Excerpted from The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory by Jesse Walker. Copyright © 2013 by Harper. With permission of the publisher, Harper Collins Publishers.