David Cay Johnston, long one of the country’s top investigative reporters, has covered crime, the LAPD and written for police magazines and other publications on policing strategy and tactics. He has also been a gun owner (revolvers, rifles and shotguns), and got a near-perfect score in LAPD combat simulation training.

The National Rifle Association has proposed a bold plan to make children safe from mass murderers by creating a “shield” around these schools whose primary defense mechanism would be guns.

We should examine this idea to see what it would cost, what societal changes it would entail and, most importantly, whether it would be effective.

If the NRA is right, then we ought to do it. But is the NRA on target?

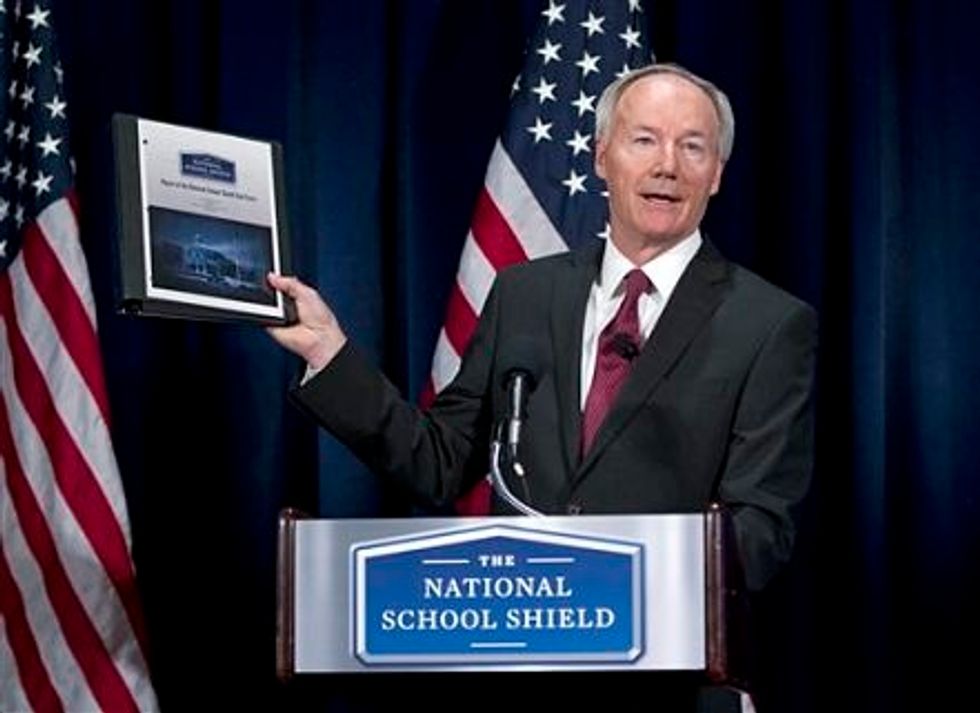

Asa Hutchinson, the former congressman and federal prosecutor who chaired the National School Shield Task Force, will not say how much he and the 12 other committee members were paid or how much of that money came from the NRA, which formed the committee three months ago following the murders of 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newton, CT.

None of the 13 committee members named in the 225-page is an educator. However, all of them have a financial interest in security training.

Five of the 13 committee members describe themselves as employed by Phoenix RBT Solutions. Its website says it “offers reality-based training solutions for law enforcement, military and private sector security at the national and international level. ” One of its products is called “ultimate training munitions.”

The report says each district should make its own decisions, which is smart since the committee has no authority and is simply an arm of the National Rifle Association.

But to examine its proposal we should look at the cost of placing a “school resources officer,” as the NRA euphemistically calls these “sworn law-enforcement officers” at every school. Why? Because that is what a shield implies and protecting only some schools would simply make the unguarded schools more inviting targets for mass murder, an idea marketed by the NRA.

America had almost 99,000 public schools, another 33,000 private schools and close to 7,000 colleges in 2010.

That’s almost 139,000 locations to guard without counting daycare centers and other places where children gather, like YMCAs/YWCAs and Little League fields. For simplicity, we will stick to the schools.

The committee report cites a cost of $10,000 per school for a security consultant. That’s $1.4 billion, though the report suggests this cost could be lower, so we’ll count it at just a billion.

Many kindergarten through 12th grade schools are open from 7 in the morning until 9 or 10 at night because of pre-school and after-school programs, night high-school and evening college classes, not to mention weekend programs, sports contests, student newspapers and broadcast stations, band practice and other ancillary activities.

And while schools generally let out for long summer vacations, many continue to operate, offering summer schools, sports, childcare and so sports, debate and other teams can practice, as well as other activities. Since the NRA does not propose to end these activities and they take place at schools, we can reasonably include them within the proposed NRA shield.

So while many campuses are busy up to 15 hours a day during the week and for 10 hours on weekends, let’s not count all 85 or so hours of operation each week, but be conservative at just 50 hours a week of armed guarding.

One armed guard on duty at all times would not be enough.

Columbine High School had an armed guard, but he was outside helping some of the 21 wounded, not shooting it out with Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold as they murdered 12 of their classmates and one teacher.

When police arrived, they did not enter the school to shoot it out with the murderous pair, either. Instead they secured the perimeter, showing that the presence of armed officers does not mean someone on a murderous rampage will be stopped with police bullets. Harris and Klebold shot themselves.

To cover meal and bathroom breaks, meetings and the like means each school would need at least two guards to make sure at least one is on duty at all times.

At many schools two guards would not be sufficient because of the size of the campus and its openness. My California high school is as open today as it was when it opened in 1963, so you would need perimeter patrols or fencing. Ditto each of the schools my eight children attended over the years in Northern and Southern California, Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and western New York.

Fencing would allow funneling everyone entering a campus through one or more points, but that would mean both delays (time is money) and more guards to check those coming and going. We will ignore the labor costs of teachers and others waiting in line.

Basic, classic school chain-link fencing would not keep schools safe. A determined killer could just cut the fence and enter in a minute or so.

That suggests a need for security cameras and either live monitors or sophisticated software that can distinguish between a bunny and an armed intruder at the perimeter. Some, perhaps many, locations would require tennis-court high fencing or razor wire atop the fences to prevent scaling them.

Ignored here is the whole idea of our turning schools — where we want the human mind and spirit to flourish — into something akin to a junior-grade prison.

So what will armed guards cost?

Police officers and detectives at the median – half make more, half less – made $55,010 in 2010, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Average pay was higher. Adjust for inflation and the median pay this year would be $58,600.

Of course security guards can be hired for much less. Median pay for security guards was less than half that of cops at just under $24,000. So adjusted to 2013, that would be about $25,500.

But security guards typically are not armed and are not, as the NRA report calls for, “sworn law enforcement personnel.”

Using the median pay of police, assigning two officers to each school for 50 hours a week would cost $16.3 billion annually just for salaries. Of course we would need many more guards because many are, like the school I attended long ago, open.

That $16.3 billion annual cost only covers time while actually on guard.

Training, sick leave, court appearances and time diverted to such things as keeping records, writing reports and being a witness at a school disciplinary hearing or even a court hearing will reduce time being a guard. Some big police department budgets show that it takes nine officers to put a patrol car on the streets for the 168 hours in a week, implying that officers spend less than 19 hours of a 40-hour work week on the streets.

Armed school guards will not have as many extra demands on them as street police, but they will have some. Instead of 19 hours of actual guard work in a 40-hour week, let’s assume 35 on patrol and five on paperwork, training and the like.

That means about 6,000 hours of paid time are needed for two guards at each school for 50 weeks a year, the equivalent of 2.9 full-time guards for minimal coverage.

That brings the total salaries to $23.5 billion annually without considering all the large or open schools that would need many more guards.

But there’s more. Fringe benefits, employer payroll taxes and other benefits typically boost the cost of compensation by 30 percent, bringing total compensation to $30.5 billion.

Then there’s training. Police departments often spend well more than a year’s salary on training recruits, including psychological fitness tests. Just as we test airline pilots to make sure they have not become disturbed — since they could commit suicide by jetliner and take many innocent lives — surely we will want to periodically evaluate these armed school guards to make sure one of them will not turn out to be a mass killer.

Then there is the problem of un-teaching these new hires.

What recruits typically pick up about law enforcement from TV and movies is just plain wrong and dangerous. Taxpayers spend a small fortune already to un-teach police officers.

These armed guards will need to be taught Constitutional, criminal and family law, not to mention specific training for working in school environments where small children may be frightened by their presence and older ones may mock them or engage in pranks.

How long would it be before some student pulling a black cellphone from his pocket was shot dead by an armed school officer who mistook it for a gun? On the streets, it happens.

They will need to know how and when they can stop and frisk a student, a teacher and a visitor, all of whom have different legal rights. They will need to learn the nuances of questioning both suspects and witnesses and how to maintain chain of custody for evidence so no criminal case will be dismissed for failure to properly handle the proof. And sensitivity training to reduce complaints, and lawsuits, alleging racist, religious and genderist discrimination.

Then there is the un-training needed to deal with armed combat.

While the fictional Dirty Harry boldly walked down the street in San Francisco firing his .44 at armed bad guys, in real life police are taught to take cover, fire one or two shots and assess while keeping count of how many bullets they have left.

There is a word for armed law enforcers who in real life act like Clint Eastwood’s character, the head of the LAPD police academy told me when I covered that institution for the Los Angeles Times: Dead.

The NRA committee recommends 40 to 60 hours of training.

In South Carolina, not known for its heavy regulation of business, it takes 1,500 hours of training to become a barber. To get a big rig truck license requires 40 hours in class and as many as 120 hours behind the wheel for both road and delivery yard maneuvering.

The barber and trucker training may be excessive, but 40 to 60 hours to train armed guards working around children is not going to cut it. And training is not a one-time expense, but a recurring cost.

And who is going to pay for more shooting ranges for these guards to maintain their proficiency? That, plus ammunition and the paperwork to track the results, is another cost taxpayers would have to bear.

Then there is overhead — supervisors and supervisors’ supervisors, account clerks and budget analysts and file clerks and background investigators to make sure someone planning a school murder does get hired as a guard.

Using a widely applied rule of thumb in business, let’s conservatively estimate overhead at a 10 percent add-on.

The cost, so far, comes to $34.6 billion per year for consultants, pay, fringe benefits and overhead. That’s almost $450 per student per year.

Fencing, monitoring gear and lost time at checkpoints would be in addition.

Oh and there’s another problem. There would be a very good chance that in a shootout some of the dead would be kids killed not by armed invaders, but the armed guards whose duty it is to protect the children.

In reconstructions of police shootings, it is common to find that the vast majority of bullets not only missed their target — they went wild. That happens in real life when the adrenaline is pumping, adding to the fog of conflict.

Look at what happened when LAPD officers opened fire on a slow-moving bright-blue pickup with two Hispanic women they mistook for Christopher Dorner, the murderous former officer who was large, black and drove a grey pickup of another make and model.

Only one of the two women, an elderly grandmother delivering newspapers, was hit in the fusillade, while nearby trees, cars and garage doors were peppered with bullets.

Numerous official studies and reports of specific incidents show that only a small minority of bullets fired by police in combat hit their opponent, even at close range.

Officers facing suspects whose guns can fire many bullets rapidly are at risk of being hit by a spray of bullets, rather than aimed shots. That may auger for Kevlar vests and helmets for these armed school guards.

But because students would be nearby or even in the direct line of fire, it would be unconscionable to arm school guards with automatic or semi-automatic weapons that could kill the very people whose lives the guards were sworn to protect.

The understandably scared school guard who kills just one child would mean more money on lawyers and settlements, not to mention the awfulness of death-by-protector.

Of course we could avoid such costs by passing a law blocking lawsuits, in effect telling any parent whose Johnny or Jane was shot or killed by a school guard, “tough luck.”

Another problem, and cost, would be securing the guards’ guns and ammunition when not in use. The guards will probably need a break room, computers to make and file reports of their activities and gun lockers that not even the smartest and most determined school mischief-makers can get into.

Walmart sells what it says are secure gun lockers for as little as $97, but you can bet these would not pass muster with law enforcement and school officials or their lawyers.

Then there is the seemingly minor problem of keeping track of keys to these lockers, keys that need to be secure and yet readily available in the event several armed invaders come and more firepower, and ammunition, is needed.

Finally, we assume the armed guards will get the drop on or at least react effectively to an armed intruder or intruders.

But a determined school killer will simply figure out how to take out the guards, maybe one at a time, perhaps when they are standing together sipping coffee and chatting about how nice and quiet it is now that all the little ones are in class.

Once the guards have been dispatched, the invaders could kill at will until they run out of ammunition, their weapons jam or police and guards from elsewhere arrive, get onto the campus, figure out where the killers are and confront them or, as police often do, just form a perimeter to contain them, effectively leaving the innocent at risk and protecting themselves from danger.

Now let’s think about the cost-effectiveness of prophylactic protection that regards every student’s life as equal, which would cost $34.6 billion annually, not counting capital costs (fencing, electronic monitoring, etc.).

From 1980 through 2012 there were 297 students and others killed in school shootings, or an average of nine per year.

But since the 32 murders at Virginia Tech, the trend has been toward larger numbers. So let’s generously assume the “school shield” prevents 50 murders per year. The cost would be $692 million per life saved.

While no one wants any child killed, such a large cost brings up the question of whether there is a more cost-effective and economically efficient way to achieve the same goal. Are there alternatives that would do as well or better at less cost?

And if we turn our 139,000 public and private places of learning into armed camps and it works, what would someone hellbent on the mass murder of students do?

We need to consider that the NRA approach would work and, if it did, what response it would generate from the Adam Lanzas of America.

People, even delusional people, who want to kill as many children or college students as possible spend long periods of time fantasizing, planning, and studying other shootings so they can do the most harm.

So if we fence, monitor and staff our schools with armed guards what would we expect of would-be killers?

A hint can be found in the annual reports issued by the Ohio firm National School Safety and Security Services, which collects reports of school deaths, shootings and violence.

Many of the reports it counts took place off-campus as students were going to or from school, whether riding on school buses in Alabama or just walking.

A determined mass killer, knowing a school has armed guards, is fenced and monitored, would just look off-campus for gatherings of students. The Friday night football game? A car wash for charity? Or even getting a co-conspirator to start a fight somewhere to draw a crowd.

Figuring out the cost of shielding students in these and innumerable other possibilities – well, that’s as dumb an idea as what the NRA committee proposes.

AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana