Oct. 11 (Bloomberg) — From the moment it was introduced in Congress in 1866, the 14th Amendment has inspired intense political and judicial controversy. Most has centered on the first section, which declares that any person born in the U.S. is a citizen and prohibits states from depriving such citizens of life, liberty, property or the equal protection of the laws. The second and third sections — a complicated formula related to determining states’ representation in Congress, and political disabilities imposed on former leaders of the Confederacy — have fallen into abeyance.

Until recently, the fourth section, which mandates that the “validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned,” while prohibiting payment of the debt incurred by the Confederacy, has attracted little attention (except from Southerners who over the years have hoped to be repaid for the money their ancestors patriotically lent to the secessionist government). With the threat that the U.S. may be unable to pay bondholders if Congress fails to raise the legal debt limit, Section 4 is suddenly in the news.

The 14th Amendment had two essential purposes: to deal with an immediate political deadlock between Congress and President Andrew Johnson and to place in the Constitution Northern Republicans’ understanding of the meaning of victory in the Civil War. Johnson, who succeeded to the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination, was inflexible, deeply racist and out of touch with public opinion in the North. He opposed every action by Congress that sought to protect the basic rights of the newly freed slaves. He may have been the worst president in American history.

But more than simply resolving a political impasse, the 14th Amendment sought to place the results of the Civil War — emancipation, Confederate defeat and the consolidation of national authority — beyond the reach of shifting congressional majorities. Inevitably, the still-bitter Democrats would one day come back into power. Laws could be repealed; a constitutional amendment would be permanent. The fourth section was meant to protect against a future repudiation of the national debt.

Both sides in the Civil War relied on a combination of levying taxes, issuing paper money and borrowing to finance the war. The federal government sold more than $2 billion worth of bonds, some marketed to ordinary Northerners but most to wealthy individuals and, especially, banks. Indeed, the 1864 law that established a new system of national banks required them to purchase large amounts of these bonds if they wanted a federal charter.

While the conflict raged, some Democrats denounced the debt as the product of an unjust war and called for its repudiation. After the Union victory, no one explicitly advocated repudiating the bonds; the debate was over how they should be paid off. During the war, the Union government issued the first national currency: paper “greenbacks.” Their value deteriorated as time went on, but they were legal tender and could be used to purchase federal bonds. To make the bonds attractive to investors, interest was paid in gold and exempted from taxation. But some of the bonds didn’t specify how the principal would be paid when the loan became due: in depreciated paper money or in gold. Naturally, banks insisted on the latter.

In 1867, as the debate over ratification of the amendment was taking place, a prominent Northern Democrat, George H. Pendleton of Ohio, appealed to the popular hostility toward bankers and proposed to redeem federal bonds in greenbacks. The bonds, he pointed out, had been bought with paper money; to pay the principal in gold would give investors a gigantic windfall. The Democrats’ national platform of 1868 endorsed the “Ohio Plan.” Meanwhile, President Johnson advanced the novel suggestion that interest payments be counted as reducing the bonds’ principal. Republicans reacted with fury. To them, the sanctity of the debt was a moral legacy of the war, and they equated the Ohio Plan with outright repudiation. The Republican victory in 1868 settled the debate. The bonds were eventually paid off in gold, and investors reaped a tidy profit.

Today, of course, the lineup of parties in the national-debt debate has reversed. In 1866, the president did everything in his power to thwart forward-looking actions by Congress. Today, the House of Representatives is hellbent on obstruction. The heart of the party of Lincoln now rests in the Old South; Republicans have become obsessed with states’ rights, while Democrats have become the proponents of national authority.

Does President Barack Obama, as some have suggested, have the power, under the 14th Amendment, to raise the debt limit unilaterally to secure the constitutionally mandated “validity of the public debt” and pay the government’s obligations? It’s unclear. Almost no jurisprudence exists on the question. The fifth section of the 14th Amendment grants Congress the power to enforce its provisions. Whether this prohibits the president from also doing so is hardly clear, and how the Supreme Court would rule is anybody’s guess. But it seems doubtful that many investors will be attracted to bonds whose legality is subject to years of litigation.

One lesson of history seems self-evident: Whatever happens, bankers always manage to come out ahead.

(Eric Foner is the DeWitt Clinton professor of history at Columbia University.)

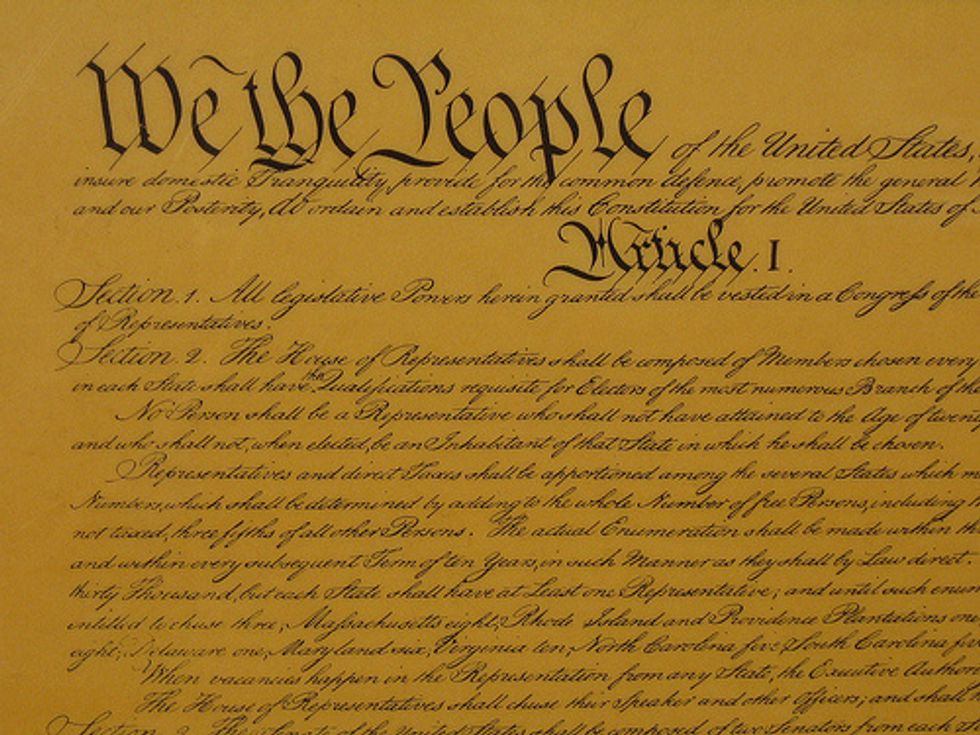

Photo: Adam Theo via Flickr