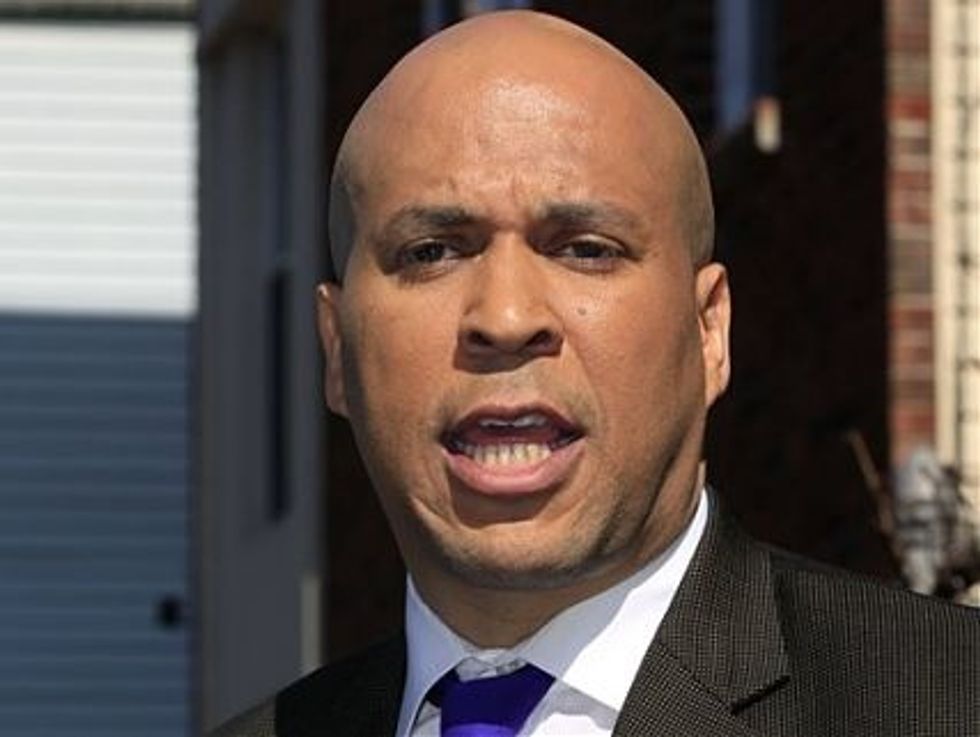

Cory Booker’s emotional televised plea to “stop attacking private equity” may have been the single greatest service he could perform for the Romney campaign. His immediate attempt to revise his remarks on behalf of President Obama, for whom he is supposed to act as a surrogate, only highlighted his earlier insistence that the harsh campaign criticism of Bain Capital, which he specifically defended, is “nauseating.”

But the Newark Mayor’s feelings must be influenced by his own relationship with Wall Street, private equity, and Bain. America’s financial titans have been very, very good to him.

Although Booker undoubtedly knows that Bain is fair game – as he later acknowledged, going so far as to accuse Mitt Romney of “not being completely honest” about job creation there – his initial remarks were obviously sincere. He tried to equate negative advertising about Bain with the Republican disinterment of the embarrassing Reverend Jeremiah Wright, and went on to denounce the impact of “this unbelievable amount of campaign cash that’s eroding, in my opinion, the democracy, but more important, pulling our campaigns in the gutter.”

Even a cursory examination of Booker’s own political history shows, however, that he has never hesitated to use negative advertising against his opponents, when necessary – and that his own remarkable rise to power in Newark was funded by overwhelming infusions of cash to pay for those ads.

The first time he ran for Mayor and lost in 2002, Booker was heavily outspent by then-Mayor Sharpe James — later sent to prison in a federal corruption probe — but managed to raise and spend almost $2 million, much of which he spent on ads attacking the incumbent. Four years later, thanks in part to Street Fight, a superb documentary film about the first race that might be considered the longest negative ad in history, Booker won easily with a massive, $6 million warchest against a struggling opponent who raised less than $200,000.

When Booker ran for his second term in 2010, he faced token opposition but raised more than $7.5 million, largely from the same Wall Street and private equity financiers that have always been his primary source of outside support. Glancing at his campaign filings from that race, it is easy to find not only major donors from Bain and other private equity firms, but big Romney backers such as Julian Robertson of Tiger Capital Management and Paul Singer of Elliot Capital Advisers, each of whom has given the Republican candidate at least $1 million in this cycle. Both Robertson and Singer gave the maximum $26,000 to Booker’s campaign.

Among the Bain Capital donors to Booker’s 2010 campaign were Joshua Beckenstein, who also gave the maximum $26,000, and Jonathan Lavine, who gave $25,000. Other top donors included members of the Curry family, who run Eagle Capital Management (and close relatives of Marshall Curry, the director of Street Fight) and gave a total of $78,000. The full list, which includes also includes large donations from executives at Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and Morgan Stanley, can be found here.

Surely Booker is aware of the costs as well as the benefits of private equity — and its mixed record as an engine of job creation. He is far too smart and experienced to misunderstand private equity’s true purpose, which is to create wealth, not employment. And Booker certainly knows that when Romney presents himself as a business man who can revive America’s fragile economy, it is fair to mention how Bain profited from loading up companies with debt and ripping off the proceeds while laying off thousands of workers.

But whatever he says about capital, the Newark mayor also knows that it takes a lot of money to win public office, like the U.S. Senate seat that may be in his future. What everyone else should know is that he expects to raise that campaign money from the same people and firms that have backed him from the beginning.

Henry Decker contributed to this story.