The rich really are getting richer, while the vast majority is getting poorer. All you have to do is look at the official government data to know this.

Sadly, though, most of our nationally prominent journalists, especially David Brooks of The New York Times and PBS, do not know this because they neglect to do a basic journalistic task. It’s called reporting.

Brooks, in his Friday Times column, looked at inequality. He gets it nearly all wrong in these two paragraphs:

At the top end, there is the growing wealth of the top 5 percent of workers. This is linked to things like perverse compensation schemes on Wall Street, assortative mating (highly educated people are more likely to marry each other and pass down their advantages to their children) and the superstar effect (in an Internet economy, a few superstars in each industry can reap global gains while the average performers cannot).

At the bottom end, there is a growing class of people stuck on the margins, generation after generation. This is caused by high dropout rates, the disappearance of low-skill jobs, breakdown in family structures and so on.

The first and overwhelming problem is that his scale is wrong, probably because Brooks just conjured up the only hard number in that passage.

Brooks writes about “the growing wealth of the top 5 percent.”

The threshold to be in the top 5 percent income group in 2012 was $161,000, analysis of tax return data by economists Emanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty shows.

That is a lot of money to most people, but it is pocket change for top Wall Streeters, the group whose pay Brooks properly calls perverse.

Lloyd Blankfein, who runs Goldman Sachs, was paid $23 million in 2012. That is 142 times the threshold to be in the top 5 percent.

Looked at another way, had Blankfein been paid weekly, his first paycheck would have shown almost 3 times the gross pay that those at the top 5 percent threshold labored all year to make.

Goldman’s 32,400 employees made $12.6 billion last year, which is as much money as the lowest-earning 6.2 million American workers made the year before.

To put that in another inequality perspective, in 2012 America had 23.3 million workers, all of them part-time or seasonal, who made less than $5,000. They averaged $2,025 each. Ponder that for a moment. About one worker in six made only $2,000.

Careful readers will note that Brooks referred to the top 5 percent of workers, not taxpayers. So, let’s look at compensation for services, as the government calls your paycheck.

How much must one earn to get into the top 5 percent?

In 2012 it was $115,000, Social Security data show.

That is much lower than the income on tax returns for two reasons. First, most taxpayers are actually two people, a married couple. Second, wages and salaries account for about three-quarters of all income with deferred wages like pension benefits pushing the share due to labor above 80 percent of income reported on tax returns. The rest is capital gains, rents, business profits and the like.

Brooks gets one thing right, what he calls “assortative mating” in which doctors these days tend to marry other doctors, not lower-paid nurses.

The result is two big incomes blended in one household. Even so, we are still talking about modest incomes compared to the Wall Streeters and others at the very top.

Say a man whose pay is at the threshold of the top 1 percent marries a man or woman at the same threshold. Their 2012 combined wages, Social Security data show, would be just under $500,000.

That is a lot of money, but still not enough to get them into the top half of the top 1 percent class of taxpayers, which started at $611,805.

Since the Internet economy was conceived in 1993, the threshold to be in the top half of the top 1 percent has risen 10 percent in real terms — while falling by almost 5 percent for the bottom 90 percent.

The inequality issue is not about the top 5 percent — or even the 1 percent. It is about the top tenth and hundredth of 1 percent versus the 90 percent. Here is what the data show:

The 90 percent’s average income in 2011 was just $59 more in inflation-adjusted dollars than in 1966, when LBJ was president.

Count that as one inch, and on the same scale the 1 percent of 1 percent line extends for almost 5 miles.

But it is worse than an inch to five miles. The next year, 2012, the 90 percent’s average income declined. It slipped to just under the 1966 level.

And how did the 1 percent of the 1 percent fare in 2012 compared to 2011? Their average income shot up 32 percent to $30.8 million. If Blankfein’s only income were his Goldman Sachs pay, he would be significantly below average in his income group.

Since 1993 the top 1 percent have enjoyed 68 percent of income growth with the 1 percent of the 1 percent getting almost a quarter of all growth.

And the 90 percent? Down 5 percent.

The median wage (half make more, half less) has been stuck at just over $500 since 1998 in inflation-adjusted dollars, while the number of people making salaries of $1 million plus more than doubled in that time with some making more than $90 million annually in salary.

These figures understate reality. They exclude the many very rich people who legally pay little to no income tax. I name some of them and show how they do it in my books Perfectly Legal, Free Lunch and The Fine Print.

Brooks dismisses as naïve if not feeble-minded the efforts to raise the minimum wage, which in inflation-adjusted terms was more than 40 percent higher in the mid 1960s, writing:

If you have a primitive zero-sum mentality then you assume growing affluence for the rich must somehow be causing the immobility of the poor, but, in reality, the two sets of problems are different, and it does no good to lump them together and call them “inequality.”

This is a strawman argument beneath the dignity of The New York Times.

Brooks cannot show, even if he tried, that any of the leading advocates for a higher minimum wage have described economics as a zero-sum game. Quite to the contrary, many of us have pointed to empirical studies showing that raising the minimum wage would increase what economists call aggregate demand, resulting in faster economic growth.

A higher minimum wage would also mean a reduced need for government services such as food stamps and Medicaid, which I, and others, have shown are a form of subsidy for low-wage employers such as Walmart and McDonald’s.

And so are wages low because of the pathological behaviors Brooks blames? Such behaviors exist, for sure. But they always have.

The facts show that wages are down because of government policies. Chief among these is the devastation of unions, which increased employer power. As unionization slid, so did wages.

Next are the so-called “free trade” agreements. They are in fact heavily managed agreements that increase profits and push down wages, just as Adam Smith explained more than two centuries ago occurs when government helping businesses inflate prices and depress wages.

Welfare “reform” flooded the market with low-skill women, driving down low-end wages, as carefully done studies have shown and the empirical wage data shows. Today America ranks first by far in child poverty and second worst in the share of work paying low wages.

And what about those “dropouts” Brooks blames? If what he wrote were on the money, then we would see the wages of those with high-school diplomas, two-year degrees and four-year degrees going up and up. They are not, as the biannual State of Working America data book shows.

What Brooks ignores is that government policy caused most of this.

Government policy, de facto rather than declared, is to take from the many to further enrich the few. Government policy is to lavish tax cuts, cash gifts and myriad subsidies on some (but by no means all) corporations and their owners while cutting benefits to those down the income ladder. And government policy has slashed the federal tax burden of the very highest income taxpayers by more than 60 percent in the last half-century, while raising that burden for the 90 percent.

What is it about living inside the Beltway that causes so many journalists, and pseudo journalists, to not see what it right in front of their faces? How can a columnist with an assistant be so thoroughly, frequently and consistently wrong on the facts as well as the concepts?

Wait, wait — I know the answer to that. Brooks and his like enjoy listening to their sources, not looking at the extensive official record. Why analyze a statistical table when you can have brand-name politicians invite you to their homes for dinner to flatter your ego? Why ask hard questions that might undermine what you wish to be true when you can bask in the comfort of ignorant bliss and keep those social invitations coming?

The empirical facts simply do not support Brooks in this column or in his overall approach to these issues going back many years. Yet he keeps collecting his paycheck because human beings buy all sorts of nonsense and self-damaging products from cigarettes to “male enhancement” pills.

The question to ask here is whether Brooks is too lazy to report, intellectually dishonest or willfully blind.

Since The Times provides him with an assistant (like all Times op-ed columnists) there is no excuse for the lack of reporting even if Brooks is lazy. I see no signs of dishonesty, which would have long ago resulted in lies that would trap him into getting fired.

That leaves willful blindness, a voluntary disability that afflicts many of our nation’s top journalists and politicians.

This intellectual and ethical disability is encouraged by the ideological marketing talent at the big “think tanks” financed by the Koch brothers and their like. The talent is paid based on their ability to get people to embrace public policies that hurt them, often while enriching the “think tank” donors.

Some of the willfully self-blind, Brooks among them, are as oblivious to the empirical facts as those who admired the fine new clothes on the emperor as he took his fictional naked stroll.

Criticisms, like this one, tend to slip away easier than eggs in a Teflon frying pan.

If you want to understand how American came to be by far the most unequal of modern nations – our inequality is comparable to Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia and Venezuela – it is not hard. You just have to open your eyes and read the facts.

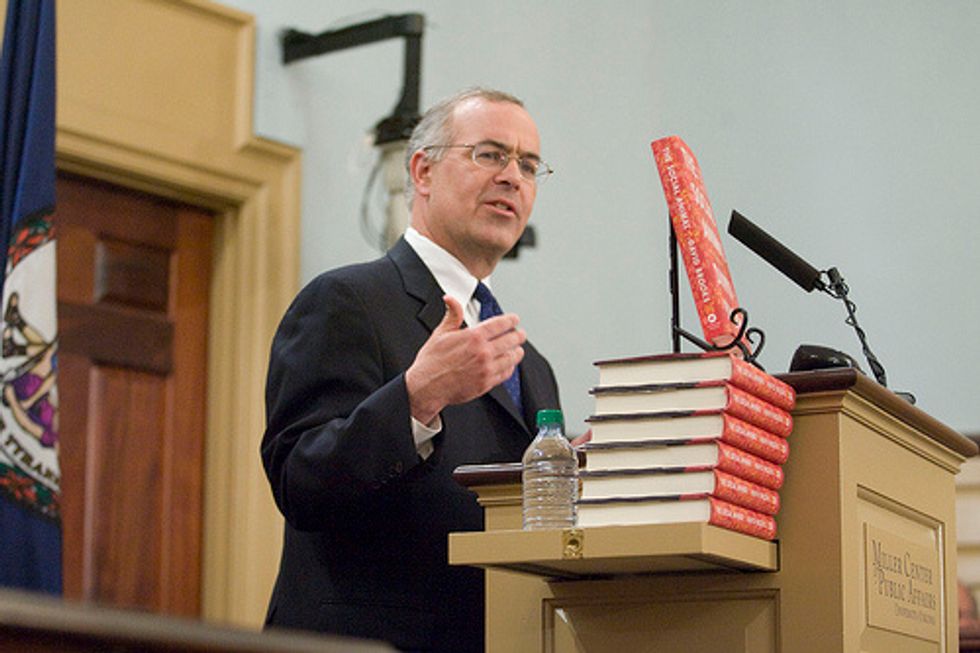

Maybe Brooks can be cured of his willful blindness. In a few weeks I will send Brooks a copy of a forthcoming anthology I edited.

DIVIDED: The Perils of Our Growing Inequality offers the informed observations of Adam Smith, the great Wall Street investor Arthur A. Robertson, Senator Elizabeth Warren and more than three-dozen others who know their stuff, know the actual issues, and the hard facts about how inequality arose and how it is being increased through government action. It is a primer for those who want to understand the issues.

DIVIDED also explains that income inequality is just one aspect of the inequality caused by perverse policies that Brooks has, so far, utterly failed to notice. Public health, access to health care, environmental hazards, education quality, work rules and incarceration all play a role in America’s awful and worsening inequality.

If you want to send David Brooks another copy of the book, this column or any other source of actual facts, his Times address is 1627 I Street NW, Suite 700, Washington, D.C. 20006.

You can read a lengthy profile of David Cay Johnston and his work here.

Photo: Miller Center via Flickr

Correction: In the mid-1960s, the minimum wage was more than 40 percent higher in inflation-adjusted terms than it is today, not a third higher as this post originally stated.