By Liz Willen, The Hechinger Report

PHILADELPHIA, Miss. — Emily Dannenberg stepped off an air-conditioned tour bus into oppressive Mississippi heat. The white Columbia University graduate student had come to this steamy rural town on Monday with a mission: to mentor both black and white teenagers and help them make sense of their state’s violent and racist past.

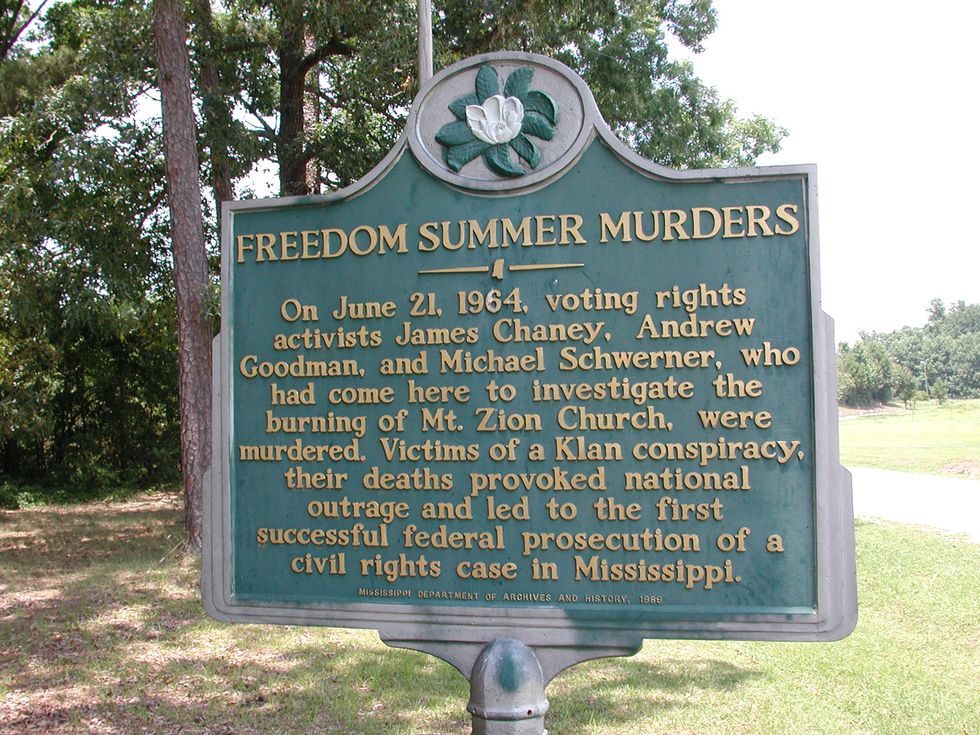

“I’d always been biased against this state, without ever visiting it,” said Dannenberg, standing near a memorial to civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney, and Michael Schwerner, who were arrested, kidnapped, and murdered during the massive volunteer effort known as Freedom Summer 50 years ago.

The three activists were setting up schools and registering blacks to vote in the Jim Crow South when they encountered fierce resistance from the Ku Klux Klan and local law enforcement. In 1964, resentment of Northerners invading their home turf on a mission to expose brutality and discrimination reached a deadly crescendo. Activists from all over are visiting Mississippi to commemorate the events and “teach greater moral bandwidth for a new generation,” according to organizers of Freedom50 events.

In the tiny town of Philadelphia, Dannenberg and a busload of high school students from the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation summer youth institute confronted the Magnolia State’s tormented legacy, including the so-called “Mississippi Burning” murders, 50 years later.

Many students on Dannenberg’s tour said they grew up in the shadow of horrific historic events, but they knew little about Freedom Summer and the sheer racist terror that characterized the era.

“It’s hard for all of us to imagine just how bad it was,” said Susan Glisson, executive director of the Winter Institute, who stood in the front of the tour bus and described cross and church burnings, racial intimidation, and the murders in meticulous detail.

“There were separate bathrooms for blacks and whites,” Glisson said. “There were separate black and white Bibles and black and white drinking fountains. Every part of Southern life was segregated . . . Fifty years later, folks are still dealing with the pain and trauma of that time.”

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. called Philadelphia “a terrible town.” His words: “This is the worst I’ve ever seen. There is a complete reign of terror here.”

Many of the events Glisson described were new to the students, who acknowledged that their civil rights education often extended no further than Dr. King and the refusal of Rosa Parks to give up her bus seat to a white passenger.

Miracle Clark, a 16-year-old black high school student from the Mississippi town of Cleveland, said she was unaware that so many Freedom Summer volunteers were white.

“I never really knew that white people could be on black people’s side,” Clark said. “When I go back to my town, I want to tell everyone about it.”

Before the bus tour, the 27 students and their 14 mentors watched Neshoba, a documentary about the murders of the three civil rights workers, chilled by footage of the trio’s burned-out blue Ford Fairlane being dragged from the Bogue Chitto swamp near Philadelphia on June 23, 1964.

A horrified nation knew that instant that the men were likely dead. Scores of students, who were about the age Dannenberg is now, were told that if they cared about democracy, they had to come south — even though in Mississippi, at that moment, they faced imminent danger.

It took another 44 days after the grim discovery of the station wagon for the badly beaten bodies of Goodman, 20, Chaney, 21, and Schwerner, 24, to be found — down a dirt road and buried beneath a newly constructed earthen dam on a privately owned farm.

Seven years later, the federal government took the case over from reticent state prosecutors, convicting just seven out of 18 indicted Klan members of conspiring to violate the men’s civil rights.

Forty years after the murders, a massive, multiracial call for justice from Philadelphia Coalition within this insular community of lumber mills and pecan trees gained traction, with additional pressure from politicians, journalists, and family members of the three men. Those efforts led to revelations that allowed prosecutors to bring new charges against an 80-year-old Klansman, Edgar Ray Killen, a preacher and sawmill operator whose 1967 trial ended in a deadlocked jury.

Photo via WikiCommons

Interested in national news? Sign up for our daily newsletter!