Reprinted with permission from Alternet.

The book that had the greatest influence on his thinking was an impassioned tract against everything he believed. George Fitzhugh’s Sociology for the South, or The Failure of Free Society, published in 1854, “defended and justified slavery in every conceivable way,” recalled Lincoln’s law partner, William Henry Herndon, and “aroused the ire of Lincoln more than most pro-slavery books.”

The dystopia of George Fitzhugh, who was descended from one of the First Families of Virginia, depicted masters and grateful slaves bound together in an ideal oligarchy for the common good. Fitzhugh drew on the authority of the Bible, bits of fanciful anthropology and the apologetics of the forgotten monarchist to create an impressionistic dream palace of communal paradise that held emotional appeal throughout the South, and which had an afterlife in the antebellum mythology of the Lost Cause down to the frolicsome plantations of Gone With The Wind.

To demonstrate the falsity of the Declaration, Fitzhugh praised inequality.

If all men had been created equal, all would have been competitors, rivals and enemies. Subordination, difference of caste and classes, difference of sex, age and slavery beget peace and good will.

He mocked the Declaration and scorned Thomas Jefferson’s famous remark against aristocratic privilege.

Men are not born entitled to ‘equal rights!’ It would be far nearer the truth to say, ‘that some were born with saddles on their backs, and others booted and spurred to ride them,’—and the riding does them good. They need the reins, the bit and the spur…‘Life and liberty’ are not ‘inalienable;’ they have been sold in all countries, and in all ages, and must be sold so long as human nature lasts.

In fragments that Lincoln wrote, dated by his private presidential secretaries to about April 1, 1854, and inspired by his reading of Fitzhugh, he wrote, “although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it, by being a slave himself.”

Applying the logic of inequality, he practiced demolishing the pro-slavery case.

You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

You do not mean color exactly?—You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own. But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.

Time and again, Lincoln ended with the proslavery advocate facing Lincoln’s relentless logic that he was the one who should be enslaved.

On the afternoon of October 4, 1854, Lincoln mounted the dais of the Hall of Representatives at the Illinois State Capitol, beneath a large portrait of George Washington. He assailed the extension of slavery to the territories under the supposed doctrine of “self-government.”

That, said Lincoln

depends upon whether a negro is not or is a man. If he is not a man, why in that case, he who is a man may, as a matter of self-government, do just as he pleases with him. But if the negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself?

When the white man governs himself, that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism.

If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that ‘all men are created equal;’ and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.

For Lincoln the revolutionary promise of the American nation, its inalienable rights, made slavery an insufferable wrong. “What I do say is, that no man is good enough to govern another man, without that other’s consent. I say this is the leading principle—the sheet anchor of American republicanism.”

With that Lincoln proclaimed the preamble of the Declaration of Independence as if it were an oath: “We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal…”

He explained, as if making his case to a jury,

I have quoted so much at this time merely to show that according to our ancient faith, the just powers of governments are derived from the consent of the governed. Now the relation of masters and slaves is, PRO TANTO, [to that extent], a total violation of this principle.

The master not only governs the slave without his consent; but he governs him by a set of rules altogether different from those which he prescribes for himself. Allow ALL the governed an equal voice in the government, and that, and that only is self government.

Lincoln had found his voice. His speech, the lengthiest he ever delivered, laid the foundation for the politics that would carry him to the presidency in 1860. His election itself became the trigger for the Southern states to leave the Union. Every Ordinance of Secession proclaimed the defense of slavery as the cause.

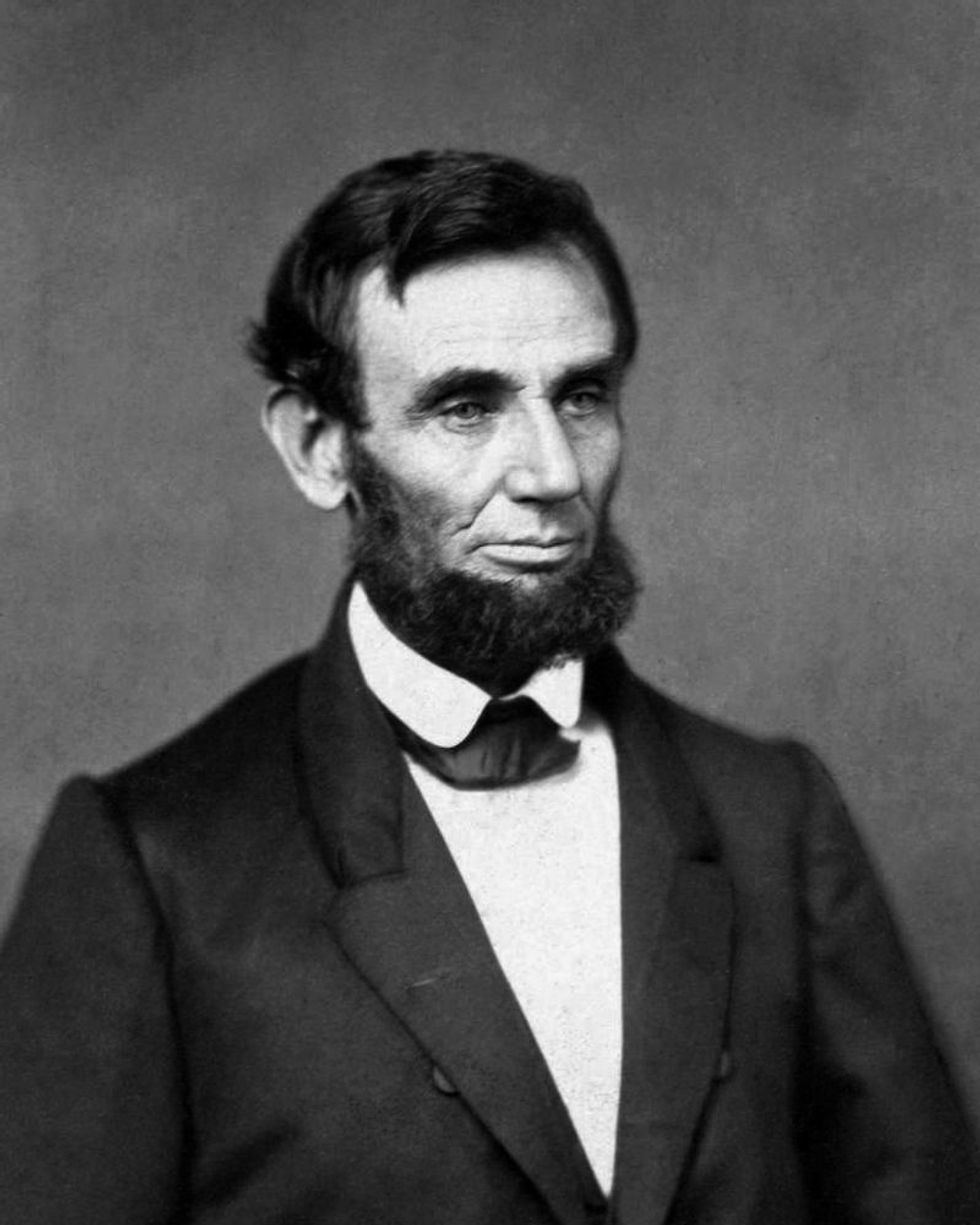

Sidney Blumenthal is a political commentator and the author of, most recently, A Self-Made Man 1809-1849: The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln.

This article was made possible by the readers and supporters of AlterNet.