WASHINGTON — Many find politics frustrating because problems that seemed to be solved in one generation crop up again years or decades later. The good thing about democracy is that there are no permanent defeats. The hard part is that some victories have to be won over and over.

And so it is with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a monument to what can be achieved when grass-roots activism is harnessed to presidential and legislative leadership. Ending discrimination at the ballot box was a way of underwriting the achievements of the Civil Rights Act passed a year earlier by granting African-Americans new and real power to which they had always been constitutionally entitled.

“The results were almost unimaginable in 1965,” writes Ari Berman in Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America, his timely book published this month. “In subsequent decades, the number of black registered voters in the South increased from 31 percent to 73 percent; the number of black elected officials increased from fewer than 500 to 10,500 nationwide; the number of black members of Congress increased from five to 44.”

And, yes, an African-American was elected president of the United States in 2008 and re-elected in 2012. He was powered by the ballots of Americans of color who would not let anything turn them around from their polling places.

President Obama’s victory has been routinely cited by those who were already insisting that the Voting Rights Act was outdated. They turned out to have a powerful ally in Chief Justice John Roberts, whose record on the issue Berman analyzes closely. If the United States could elect a black president, wasn’t that a sign that there was no longer a need for a strong Voting Rights Act?

Berman quotes Ed Blum, a tireless activist in the effort to weaken the Voting Rights Act. Before the House Subcommittee on the Constitution, Blum referred to Birmingham, Alabama’s legendary commissioner of public safety as a figure of the past: “Bull Connor is dead. And so is every Jim Crow-era segregationist intent on keeping blacks from the polls.”

In fact, Obama’s election called forth a far more sophisticated approach to restricting voting. Republicans closely examined how Obama’s political organization had turned out large numbers of young African-Americans who had not voted before. Their participation was facilitated by early voting, and particularly Sunday voting.

So legislatures in many states where Republicans had full political control went to work to make it harder for African-Americans, Latinos, and young people to vote. Of course, that is not what they said they were doing. They invented a scarecrow, “voter fraud,” to justify voter ID laws. These laws disadvantage inner-city residents and favor suburbanites who get driver’s licenses as a matter of routine. They also used all kinds of excuses to roll back early voting.

“No matter how much evidence emerged to the contrary, the voter-fraud myth would never die,” Berman writes. Indeed. The fraud specter is so useful to those who want to restrict voting that the facts don’t trouble them. As a result, a non-problem is invoked to create a massive new problem of obstructing legitimate votes.

Earlier this month, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Texas’ voter ID law “has a discriminatory effect” and amounted to a poll tax. But it also sent the case back to a lower-court judge asking her to meet a high standard of showing that the law was passed with an explicitly discriminatory intent. You can bet that the Texas voting case or another in North Carolina, or both, will make their way to a Supreme Court that has already gutted the Voting Rights Act once in a 2013 decision written by Roberts.

Will he do it again? And will voters in 2016 realize just how important a president’s power to name future Supreme Court justices is to the very right they will be exercising on Election Day?

It would have been lovely if Berman’s book could simply have celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act. Instead, it is even more useful as a guide to what still needs to be done. He tells the story of the charismatic leader of the North Carolina NAACP, the Rev. William Barber II, who led the state’s innovative Moral Monday protests.

“What do we do when they try to take away voting rights?” Barber asked at a rally.

The crowd responded: “We fight, we fight, we fight.”

There is no alternative.

E.J. Dionne’s email address is ejdionne@washpost.com. Twitter: @EJDionne.

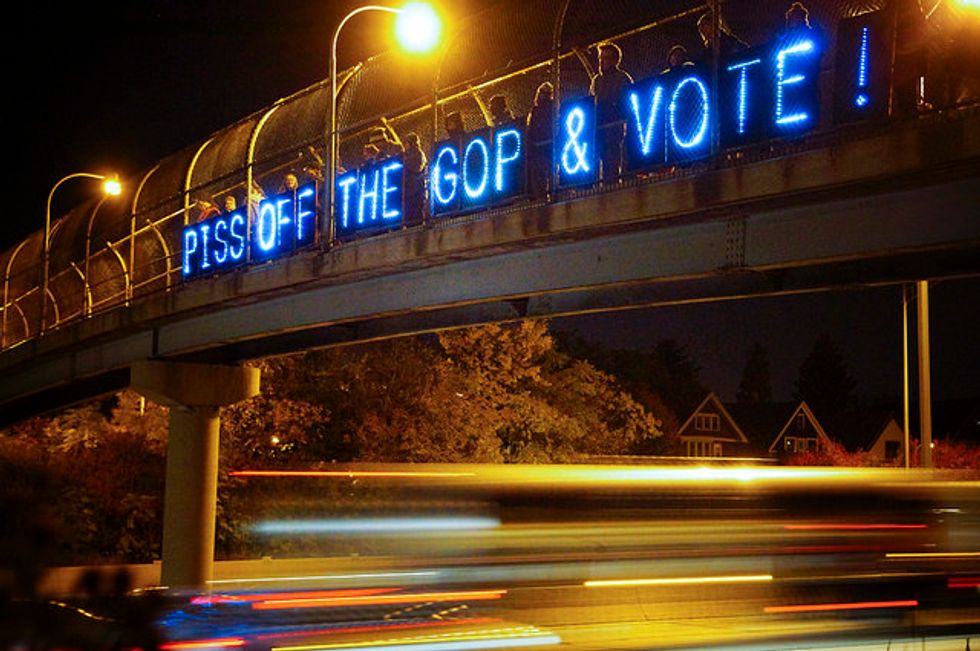

Photo: Light Brigading via Flickr