McClatchy Washington Bureau, (TNS)

WASHINGTON — When the Patriot Act expired Monday, people were left with questions as to what this means for the National Security Agency, for spying, and for the struggling presidential campaign of Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY).

Q: If some of the NSA’s surveillance powers have expired, what does that mean for the terrorists?

A: It doesn’t mean much. The NSA can still track suspects, it’ll just be more difficult.

There are three main provisions that expired.

The first, Section 215, required businesses to turn over data that’s relevant to NSA investigations. That enabled the NSA to collect sweeping amounts of metadata on Americans and store it up to five years. For perspective, most phone companies store call logs only for 18 months.

The second was an unused provision that allowed the NSA to wiretap suspects who weren’t part of larger foreign terror organizations, such as al-Qaida.

The third targeted suspects who often change phones, allowing the NSA to have roving wiretaps that covered any devices the suspects may use. With the expiration, the agency would have to get individual warrants for each communication device used.

But there’s a grandfather clause that applies to all three provisions. The NSA can continue using its authority under the laws for all investigations that began before Monday.

For established terrorists whom the agency has been tracking, the expiration means nothing. But in terms of identifying new terrorists and terror plots, the NSA’s job has become more challenging.

If the USA Freedom Act the House of Representatives passed becomes law, the provisions could be reinstated.

Q: What happens now?

A: Even though the NSA’s spying powers expired at midnight Sunday, chances are they won’t be out of commission for too long. The Senate could call a final vote on the USA Freedom Act and pass that bill as soon as Tuesday.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. R-Ky., is pushing what he calls “modest amendments,” however, which could extend the bill’s time in Congress. These amendments would require approval from the House before the bill could be sent to the president to be signed into law.

McConnell’s proposed changes include a provision that the director of national intelligence would certify the new system and a requirement that private telephone companies give the government a heads up if they change their data retention policies.

Although these probably won’t meet much resistance, some of McConnell’s amendments are likely to attract more debate, including one that removes the requirement for the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to make certain surveillance orders public and another that introduces a longer transition period to the new system.

If the Senate approves an amended version of the USA Freedom Act, it has to go back to the House. The original version easily passed a few weeks ago by 338-88.

Q: What spying powers would change in the USA Freedom Act?

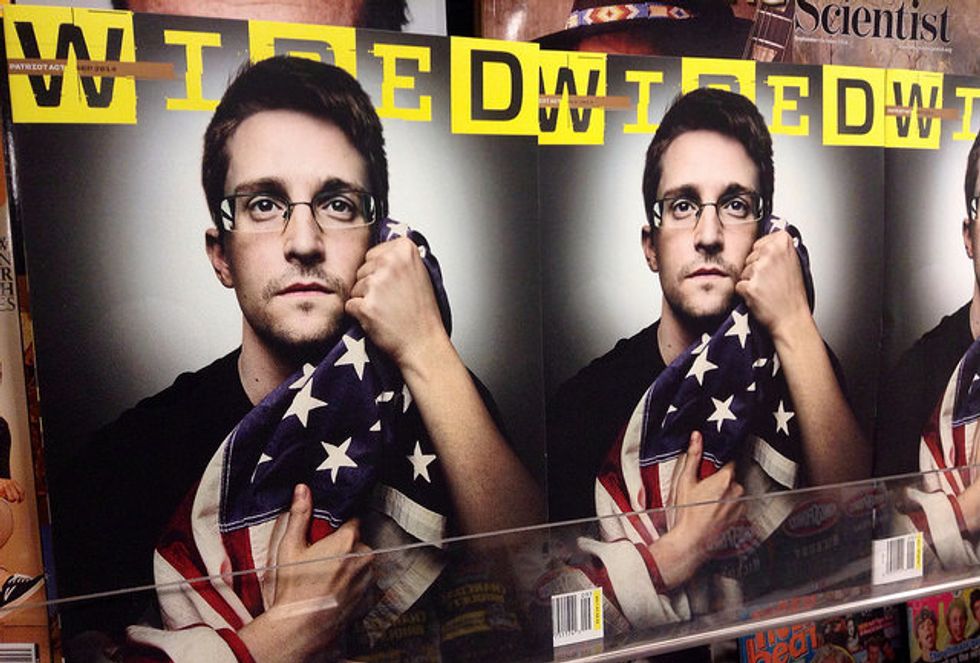

A: Generally, the USA Freedom Act is an attempt to overhaul standards for data collection by intelligence agencies, in light of whistleblower Edward Snowden’s revelations of bulk data collection by the NSA.

The bill would require requests for access to specify the data to be collected — by person, address or device, for example — instead of sweeping data collection. There’s some disagreement as to whether the bill’s restrictions would really eliminate bulk data collection. Some say the requirements for specificity aren’t strenuous enough to prevent data sweeps.

National security letters, another hotly contested, secretive way in which intelligence agencies collect data, also would require more specificity under the USA Freedom Act. The bill also calls for more oversight of non-disclosure requirements often attached to such letters. In the past, non-disclosure requirements have prevented companies from saying the government requested the information.

Under the current version of the bill, there would be a six-month transition period. The NSA would work with phone companies to create the systems needed to search records quickly and send them to the agency. McConnell is pushing for a yearlong transition period, saying it will take more time for the companies to build and test their new systems.

Under the bill, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court would have to approve all requests for data collection. The act also would provide for an advocate to represent privacy interests in the court.

Significant decisions by the secretive court would have to be declassified under the bill, but there’s an exception for findings that are a threat to national security. Companies who contribute the data are provided with avenues to report statistics on their responses to the requests.

Surveillance since 9/11

Q: Sen. Paul forced this issue from his libertarian perspective, but what does it mean for his presidential race?

A: Paul’s attempt to block the Patriot Act has put the Kentucky senator in the national spotlight, giving him attention that he badly needs as he tries to revive his lagging campaign and become a front-runner in the crowded Republican presidential field. He’s also trying to raise money on the issue, sending constant fundraising appeals asking donors to stand with him against the NSA surveillance program and send money to his campaign.

But polling suggests Republican voters in early primary states are often hawkish on national security, and while Paul is firing up civil-liberties-minded voters, he’s drawing skepticism from others he’ll need to win the nomination.

Q: How did we even get to this point?

A: The simple answer is Edward Snowden.

Before Snowden, Congress passed the USA Patriot Act in response to the Sept. 11 attacks. The act gave the NSA wide freedoms in collecting data.

President Barack Obama renewed the bill in 2011, giving it another four years.

Then in 2013, Snowden, a former federal contractor, revealed that the NSA had been spying on Americans by collecting and storing massive amounts of Internet and phone data, citing the Patriot Act. The documents he leaked generated public outcry and sparked debate.

In May, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals deemed the NSA’s collection of phone metadata illegal under the Patriot Act.

But until the act came up for renewal — and Paul filibustered the USA Freedom Act — the law hadn’t changed.

(Samantha Ehlinger, Emma Baccellieri, Daniel Desrochers and Sean Cockerham contributed to this report.)

(c)2015 McClatchy Washington Bureau. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: Mike Mozart via Flickr