Reprinted with permission from AlterNet.

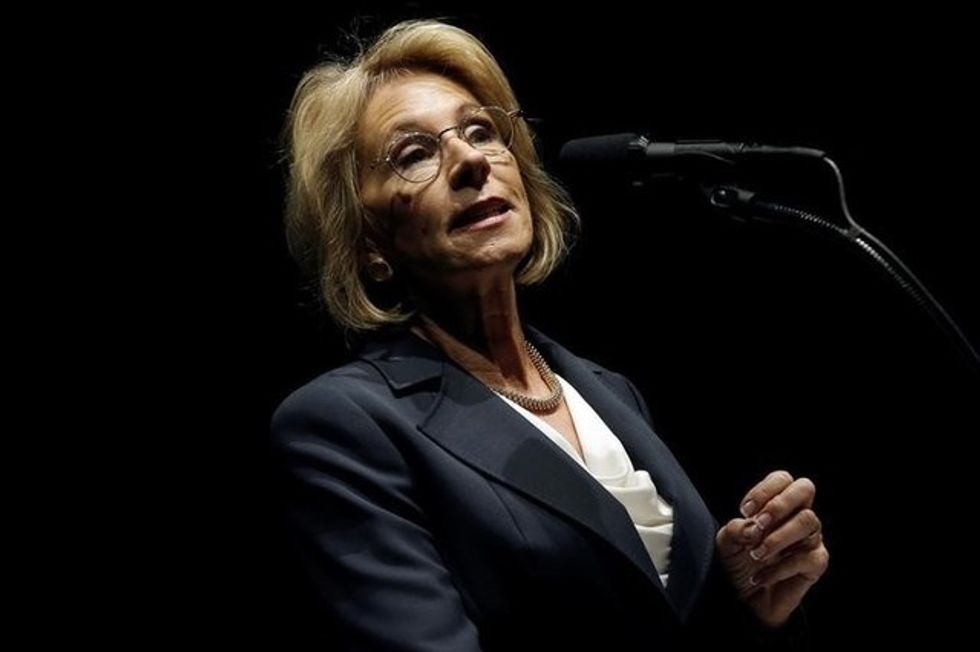

If Betsy DeVos enjoys the occasional quaff of champagne on her private jet, the recent news that the Supreme Court is poised to deliver a knock-out blow to public sector unions presented a reason to celebrate. The announcement was made just hours before DeVos alit at Harvard last week, where she was the star attraction at a school choice conference. At Harvard’s Kennedy School, DeVos was met by one of the largest protests she has encountered to date: an all-ages demonstration vs just about everything Trump’s Secretary of Education has said and done during the past seven months. Inside, the event was tense, even hostile—another rocky outing in a tenure replete with them. Or at least that is the conventional wisdom.

Turning red

The latest Supreme Court case to take aim at unions, Janus vs AFSCME Council 31, got its start two years ago with a suit filed by yet another right-wing billionaire: Illinois’ Bruce Rauner. While it is framed by conservatives as a case about individual rights and freedom, the aptly named “Janus” is about politics and power. Public sector unions, among the only unions left at this point, provide the bank and the foot soldiers that get Democrats elected, and at their best they’ve spearheaded progressive causes that go far beyond the interests of their members. In Massachusetts, the teachers unions have been the driving force behind successful campaigns for a minimum wage hike, paid sick time for all workers, and are now pushing a tax on millionaires. The unions are also virtually the last organized defense of what’s left of our safety net—Social Security and Medicare; the right wants those next.

Just days before DeVos appeared at Harvard, she was back in Michigan, taking what was essentially a victory lap. She exhorted the crowd at a conservative gathering on Mackinac Island to pat themselves on the back for the Mitten State’s having gone Republican in the 2016 Presidential election—the first time since 1988. “We in Michigan have a lot to be proud of, but nothing more than that,” DeVos said. The story of just how the DeVoses pulled off the feat of turning Michigan red is long and ugly, involving mountains of cash, the steady erosion of representative democracy, and a decades-long effort to dismember the state’s once powerful teachers union: the Michigan Education Association.

Michigan went right-to-work in 2012, thanks to legislation that was ushered into the former cradle of industrial unionism via the DeVos’ trademark combo of political arm twisting and largesse. Another DeVos-inspired law made it illegal for employers, including school districts, to process union dues, while simultaneously making it easier for corporations to deduct PAC money from employee paychecks. This summer the DeVoses succeeded in driving a final nail into the MEA’s coffin. The GOP-controlled legislature essentially eliminated pensions, among the last tangible benefits that teachers in Michigan receive from their unions. The union leaders I spoke to when I traveled through the state last year, reporting on DeVos’ education legacy, were candid about the increasingly precarious state of their organizations. But far worse lies ahead. The demise of retirement benefits means that new teachers have little incentive to join the unions; the shrinking terrain of collective bargaining gives veteran teachers little reason to remain in them.

Dark money days

The specter of Harvard students, standing in silent protest during DeVos’ talk at the Kennedy School was a powerful one; the banner declaring “Our Students Are Not 4 Sale” a blunt rejoinder to a vision in which schools are akin to food trucks, a sentiment she expressed at the event. But the sign reading simply “Dark Money” may best have captured DeVos’ ethos, her family’s M.O., indeed her very path to the Trump cabinet.

The sign was actually a reference to a current dark money controversy simmering in Massachusetts, where the chair of the Massachusetts Board of Education, Paul Sagan, secretly chipped in $500K from his own deep pockets in an effort to sway last year’s ill-fated campaign to expand the number of charter schools in the state. (Sagan’s defense was that he didn’t want to be perceived as politicizing the issue). The organization that bundled the contributions of Sagan and an array of out-of-state billionaires was later spanked with the largest campaign finance fine in Massachusetts history, a ruling that is now being touted as a potential gamechanger for states that are awash in untraceable cash.

Protesters carried signs demanding that both DeVos and Sagan be “dumped,” but only the latter was tarred with the dark money brush. Even among DeVos’ detractors, her role in ushering in our new era of dark money has gone largely unheralded. Campaign workers gathering signatures among the demonstrators for a ballot measure that would reduce the influence of money in politics had no idea, for example, that DeVos herself was a driving force behind Citizens United. But as Jane Mayer describes in Dark Money, removing any restrictions on political spending has been central to the family’s mission, dating back decades. Long before Betsy DeVos was railing against the “red tape” that stifles public schools, she and her clan were seeking to free the campaign finance system from the burdensome regulations limiting the size of the checks they could write, and through them, the family’s political influence.

The family funded one long-shot legal challenge after another targeting various campaign finance laws. In 1997, DeVos became a founding board member at the James Madison Center for Free Speech, an organization that had as its stated goal ending all legal restrictions on money in politics. “Soft money,” DeVos wrote in a column for the Capitol Hill magazine Roll Call, was just “hard earned American dollars that Big Brother has yet to find a way to control.”

That the balance of power has shifted from parties to a handful of outrageously wealthy zealots, “a tiny, atypical minority of the population,” as Mayer described, is now undeniable. See for example, a recent New York Times story about the coming battle of the billionaires, in this case Mercer vs. Koch, over whose grim libertarian vision of the future will be imposed upon the rest of us. Unions are among the last brake on this transfer of power. Now they’re under existential threat.

DeVos lite

A recent poll found that DeVos remains the most disliked official in Trump’s cabinet—not an easy feat to pull off in a gallery of rogues. The depths of her unpopularity are due, not to to the fact that liberals and progressives hate her harder, but because her divisiveness crosses partisan lines. When I traveled to Van Wert, OH this spring to take in the spectacle of a joint school visit by DeVos and the American Federation of Teachers’ Randi Weingarten, I encountered one Trump supporter after another who still liked their guy, even his other cabinet members, but not DeVos. Her signature issue, using taxpayer dollars to send kids to private religious schools, has never been popular with voters, and her Margaret Thatcher “there is no school system” line makes little sense in places like Van Wert, where local schools play an outsized role in binding communities together.

In other words, this should be fertile territory for Democrats. But the coming decimation of public sector unions also means that the Democrats will be more dependent than ever on corporate money, especially from the financial sector. Accept the growing influence of the party’s biggest donors, comprised of Wall Streeters, hedge funders and Silicon Valley elites, and you also get their cramped and narrow vision of what is possible. And the moneyed influencers within the Democratic Party share a vision of education—personalized, privatized, union free—that’s increasingly difficult to distinguish from the one DeVos espouses.

After seven months on the job, DeVos may finally be shrugging off the “nitwit” rep she earned during her disastrous confirmation hearings. Her Title IX speech at George Mason was sophisticated and skillful, winning plaudits, even from critics. At the Harvard protest, I spotted but a single reference to grizzly bears, on a sign that lay abandoned on the sidewalk. As for the Secretary herself, she gives every indication of being quite pleased with the progress she’s making, and why shouldn’t she be? “Hasten slowly,” is how DeVos described her family’s motto in a recent interview. DeVos’ own family, and the one she married into, have sought to impose their vision of a country free of unions and dependence on government, including “government schools,” for two generations. Now, after decades of slow hastening, they’re almost there.

Jennifer Berkshire is the education editor at AlterNet and the co-host of a biweekly podcast on education in the time of Trump.