In the 1970s, my politically conservative father kept a small collection of comedy albums in our suburban home near Berkeley. I’m not sure how — my oldest brother may know better — but a Richard Pryor album appeared and went into heavy rotation. Craps (After Hours) was raucous and exhilarating. I still recall several outrageous bits, but Pryor’s sensibility also made a powerful impression on me. Profound irreverence, I gathered at the ripe old age of 12, was an acceptable social posture, even for adults. When reinforced by that period’s iconoclastic literature and film, Pryor’s influence almost unfit me for life in America — or most of it, anyway — during the Age of Reagan that would soon follow.

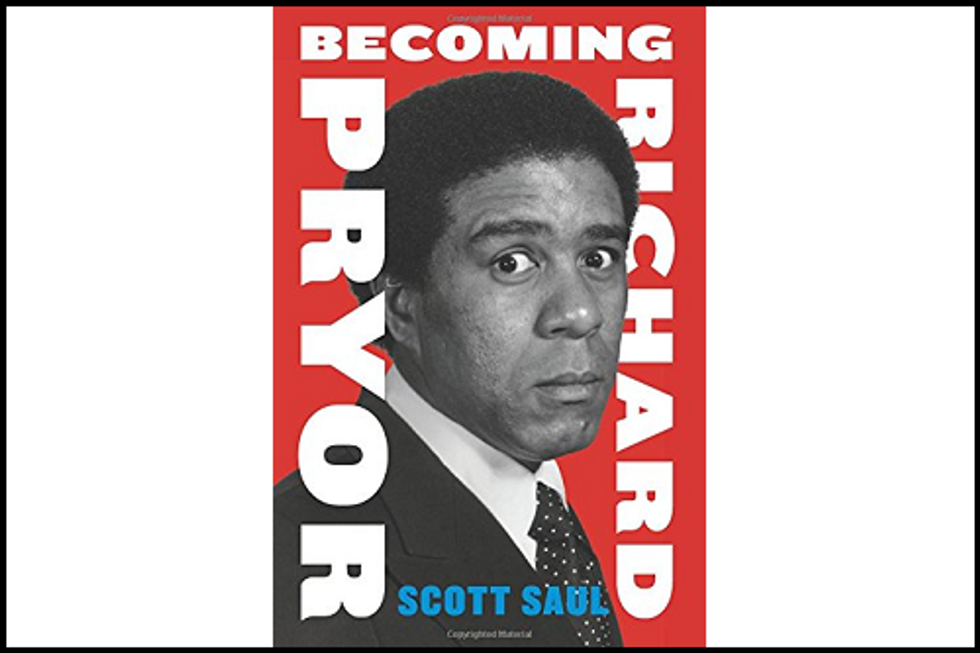

The geography in this case turns out to be important. As I learned from Scott Saul’s adroit biography, Becoming Richard Pryor, Pryor repaired to Berkeley for most of 1971 to find (or rather, to reinvent) himself. Pryor had already learned standup comedy in Greenwich Village, migrated to Los Angeles, and flopped in Las Vegas. His model was Bill Cosby, but he finished shedding that influence in Berkeley. His home base was Alan Farley’s one-bedroom apartment near campus, not far from where police scattered tear gas one week before.

Farley worked at KPFA, the nation’s first listener-sponsored radio station, and he scheduled standup gigs and a radio program for his guest. Pryor caught the eye of Ralph J. Gleason, the Berkeley resident and San Francisco Chronicle critic who also wrote for Ramparts magazine and co-founded Rolling Stone. Gleason praised Pryor as “the very best satirist on the night club circuit.” Much later, Pryor would reject comparisons to Lenny Bruce, whose comedy albums featured Gleason’s liner notes. But much like Bruce, Pryor’s post-Berkeley persona was profane, scathingly honest, and deeply political. That was the Richard Pryor I heard on Craps (After Hours), and he was amazing.

An English professor at the University of California, Saul shares the Berkeley connection. His previous book documents the efforts of John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, and others to navigate cultural crosscurrents and create new musical possibilities in the 1960s. Becoming Richard Pryor nudges Saul’s readers closer to the present, but it doesn’t try to depict Pryor’s entire life; in fact, the epilogue treats everything from June 1980, when Pryor lit himself on fire after five days of cocaine and alcohol abuse, to his death in 2005. Saul focuses instead on Pryor’s artistic formation. Thus the book’s title, which echoes Bob Newhart’s comment that after the debacle in Las Vegas, “Richard Pryor decided to become Richard Pryor.”

Who was Richard Pryor before that? A damaged child, mostly. His paternal grandmother, who raised him, also ran a brothel in the thriving vice district of Peoria, Illinois. His mother lived elsewhere, his father was a violent pimp, and his stepmother turned tricks. It wasn’t the sort of childhood that Bill Cosby had turned into comedy gold, but Saul shows how Pryor’s Peoria experience shaped his outlook, art, and turbulent personal life.

After his Berkeley sojourn, Pryor returned to Los Angeles and landed a tiny role in Lady Sings the Blues, the Billie Holiday biopic. During the shoot, his part expanded steadily until he was billed as a supporting actor. That pattern, which hinged on Pryor’s knack for stealing scenes with improvised dialog, was repeated in several other pictures. After that film wrapped, Mel Brooks recruited him to work on Blazing Saddles. Pryor, a lifelong Lash LaRue fan, wanted the role of Black Bart that eventually went to Cleavon Little. The stumbling block was Pryor’s reputation as a drug fiend. He worked on the screenplay, but many of his best lines were cut from the film. After Bart bunks with Lily von Shtupp (played by Madeline Kahn), he is asked how his evening went. “I don’t know,” Pryor had Bart reply, “but I think I invented pornography.”

Pryor didn’t appear with Gene Wilder in Blazing Saddles, but the two worked together on Silver Streak and Stir Crazy. In the former, Pryor’s limited role again grew into a substantial one. His improvisations sparked the film’s signature scene, in which Pryor applies blackface to Wilder, coaches him on his African-American disguise, and manages to skewer Hollywood’s minstrel tradition. Stir Crazy, the unofficial sequel, was the third-highest grossing film of 1981.

In the early 1980s, Saul maintains, “the future of Hollywood itself was bound up with the riddle of [Pryor’s] appeal.” The studios would solve that riddle by favoring blockbusters over what Saul calls “a certain sort of ‘1970s movie’ that sat uneasily within its supposed genre.” Pryor’s work after his self-ignition was unremarkable, and even his best roles couldn’t showcase the range and insight he displayed in his standup work. Even so, Saul makes a strong case that Pryor’s screen and television work created the necessary room for Eddie Murphy, In Living Color, Chappelle’s Show, and Key and Peele to flourish.

Pryor’s severe burn and recovery calmed his spirit, but his health deteriorated steadily after his 1986 diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Seven years later, he launched a farewell tour that focused on his life with the disease. A boxed set of his standup work appeared in 2000, and he died of a heart attack five years later. He was only 65, but much of his best work was already three decades old. In the epilogue, Saul marshals the expected tributes. Bob Newhart said Pryor was “the single most seminal comedic influence in the past 50 years,” Chris Rock named him “the Rosa Parks of comedy,” and Mel Brooks called him “the funniest comedian of all time.”

To measure Pryor’s achievement, Saul considers him as a comic, social critic, and crossover artist. Longtime friend and colleague Paul Mooney summarized Pryor’s social criticism with a single epithet: Dark Twain. But it was Pryor’s work as a crossover artist, Saul argues, that is “probably the most misunderstood and underappreciated aspect of his career.” If his television and film work couldn’t accommodate his range and depth, it was nevertheless true that his success changed an industry that largely kept black talent in a media ghetto. In his life as well as his work, Saul argues, Pryor was “crossing over” from the time he emerged, twisted but not broken, from Peoria’s red-light district. In this superb biography, Saul expertly traces those transgressions and makes the strongest possible case for Pryor’s cultural centrality.

Peter Richardson is the book review editor at The National Memo. His new book, No Simple Highway: A Cultural History of the Grateful Dead, was an Amazon Best Book of the Month in history and a San Francisco Chronicle bestseller. Richardson’s history of Ramparts magazine, A Bomb in Every Issue, was an Editors’ Choice at The New York Times and a Top Book of 2009 at Mother Jones. In 2013, he received the National Entertainment Journalism Award for Online Criticism.