Great minds, we are told, discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; and small minds discuss people. But as Gregg Herken’s carefully researched book shows, you can learn a lot about Cold War ideas and events by discussing the right people. Specifically, you can see how flaws and weaknesses in U.S. foreign policy, intelligence, and political journalism arose from a smart, largely well meaning, occasionally unhinged, and dangerously insular slice of the Washington establishment.

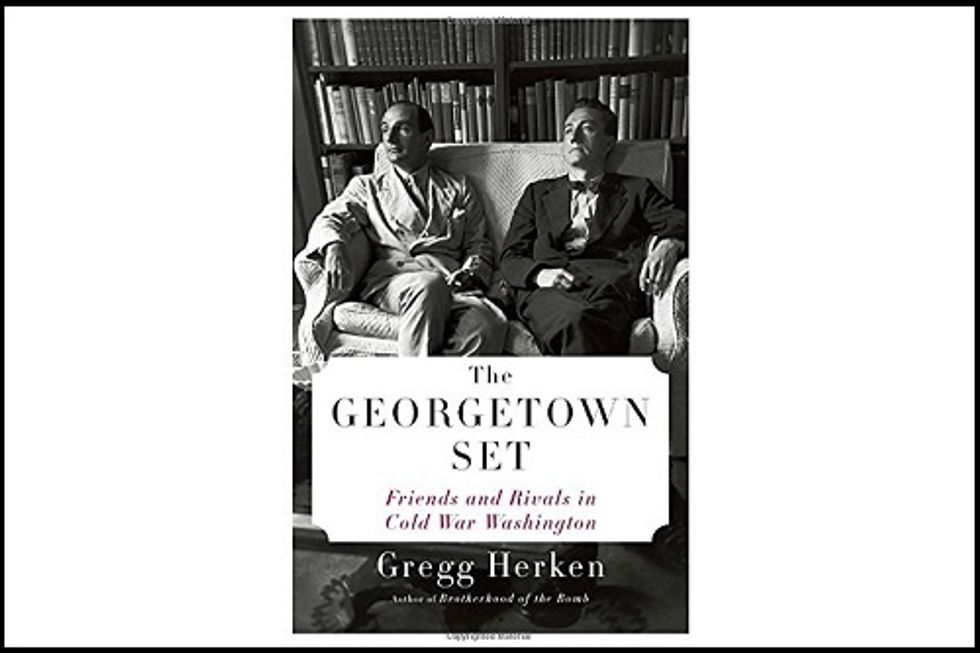

The period is familiar turf for Herken, the University of California historian whose previous books explore the development of nuclear weapons. In The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington, he turns his attention to the DC dinner-party circuit of Philip and Katharine Graham, George Kennan, Joseph and Stewart Alsop, Frank Wisner, and a revolving cast of characters that included Dean Acheson, Chip Bohlen, Averell Harriman, and John F. Kennedy. Their influence was such that one insider called those parties “a form of government by invitation,” and Herken’s detailed portrait lends credence to the book’s opening quote from Henry Kissinger: “The hand that mixes the Georgetown martini is time and time again the hand that guides the destiny of the Western world.”

Before the Second World War, Washington dinners were formal affairs, but those gave way to what journalist Joseph Alsop called “zoo parties,” featuring alcohol-fueled exchanges about politics and current affairs. At Alsop’s Sunday night suppers, party affiliation was less important than breeding and wit, and the host expected to hear strong opinions over cocktails and terrapin soup. Alsop skillfully extracted inside information from his guests, who knew that their remarks might appear in the syndicated column he wrote with his younger brother. Although Herken’s training is in diplomatic history, his book offers valuable lessons about Cold War political journalism.

The narrative also opens a window on the CIA’s early days. As director of the agency’s covert operations, the manic-depressive Frank Wisner was responsible for many debacles, and even his victories were often spoiled by downstream consequences. Other books have documented the CIA’s clubby early culture, but Herken shows how it fit the Georgetown pattern and extended to the press. It was Wisner who created the agency’s secret propaganda machine, which he nicknamed the Mighty Wurlitzer. Named after the theater organs that guided audience reactions to silent films, the program was designed to shape public opinion both here and abroad, and it relied on the New York Times, Fortune magazine, and the Alsops to put favorable spin on CIA stories. When Wisner’s fortunes fell after the Bay of Pigs debacle, he sank into depression and committed suicide in 1965.

Two years earlier, Washington Post publisher Philip Graham, who struggled with depression and alcoholism, did the same. His widow Katharine, who inherited the newspaper from her father, took over its management, grew into the role, and led the Post through the glory days of the Pentagon Papers and Watergate. But the view from Georgetown continued to shape the paper’s coverage. The Alsop column in particular was a unique mix of access and advocacy journalism; Stewart Alsop described it as “not only the news-behind-the-news but the news-before-the-news.” The column’s influence peaked during Kennedy’s presidency, but Joe Alsop also helped polish Henry Kissinger’s image during the Nixon years.

Although the book is a group portrait, Herken returns again and again to the largely forgotten Alsop, a distant relative of Theodore Roosevelt who graduated from Groton and Harvard before rising through the journalistic ranks. He was a New Deal dandy with a touch of noblesse oblige, but mostly he was a staunch Cold Warrior. (His opinion of the Soviets didn’t improve after the KGB attempted to blackmail him over a homosexual tryst in Moscow.) He wondered who lost China, called the 1953 armistice with Korea “a concealed surrender,” coined the phrase “missile gap,” adored Jack Kennedy, and goaded LBJ to take a hard line on Vietnam. During the 1960s, he visited that country in high style twice a year, largely to bolster his unshakable conviction that the war was winnable. He came to regard his younger and more skeptical colleagues, including those who were reporting fulltime from Vietnam, as traitors.

When a U.S. defeat in Vietnam seemed inevitable, Joe Alsop predicted fresh recriminations of the who-lost-China variety. As late as 1979, he told Joan Baez that she and other antiwar activists were “all blood-guilty. You had a considerable role in causing this country quite needlessly to lose a war, with the most damaging consequences to American interests all over the world … I trust you will sleep uncomfortably for many years to come because you are haunted by the consequences of your act.” Coming from an insider who rarely missed a chance to promote American state violence, Alsop’s charge was a vast projection. The finger-pointing he predicted never transpired, but one wonders whether he was completely deluded. After all, voters soon rewarded Ronald Reagan, who considered the U.S. effort in Vietnam a “noble cause” sabotaged by spineless politicians.

It’s tempting to wax nostalgic about bipartisan dinner parties and the golden age of American newspapers, but Herken reminds us that the good old days weren’t all that good. His subjects, he concludes, “bore no little responsibility for the miscalculations and disasters of that era: the danger, profligacy, and waste of a runaway nuclear arms race; reckless and costly clandestine adventures overseas; complacency in the face of political reaction at home; and, not least of all, the protracted debacle of Vietnam.” In short, the hands that mixed those Georgetown martinis had a great deal of blood on them.

Peter Richardson is the book review editor at The National Memo. His history of Ramparts magazine, A Bomb in Every Issue, was an Editors’ Choice at The New York Times and a Top Book of 2009 at Mother Jones. In 2013, he received the National Entertainment Journalism Award for Online Criticism. No Simple Highway, his cultural history of the Grateful Dead, is scheduled for January 2015.