By Chris Serres, Star Tribune (Minneapolis) (TNS)

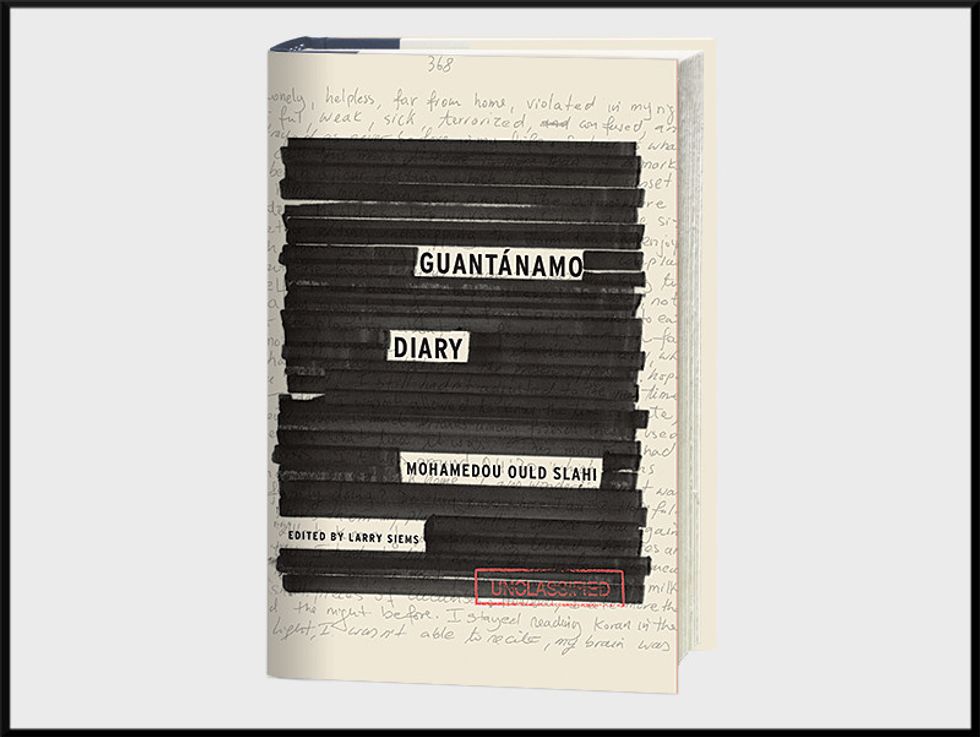

Guantánamo Diary by Mohamedou Ould Slahi; Little, Brown (466 pages, $29)

___

Near the end of his hellish account of perpetual torture, Mohamedou Ould Slahi makes what appears to be a remarkable confession.

Slahi, a prisoner at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, who wrote a 466-page memoir from his cell, admits to his captors that he planned to blow up the CN Tower in Toronto with explosives from Russia. The military interrogators who have been questioning him for four years “almost had a heart attack from happiness,” Slahi writes.

The confession, however, is an elaborate lie. It is a desperate act by a man subjected to four years of near unimaginable terror, including regular beatings, sleep deprivation, death threats, starvation, and sexual molestation. “I had to wear the suit the U.S. Intel tailored for me, and that is exactly what I did,” Slahi wrote.

More than just a memoir, Slahi’s “Guantánamo Diary” is a unique and intimate view of what happens when due process is suspended and detainees (or, in this case, “enemy combatants”) are cast into zones of nonbeing, where they are not even recognized as human. In these lawless zones, conjecture and hearsay provide the rationale for indefinite detention, and torture methods become almost limitless in their scope and sadism.

The manuscript raises a broader question about whether torture actually works. As Slahi demonstrates in his blow-by-blow account of his interrogation, the prisoners detained indefinitely at Guantánamo will say just about anything to stop the abuse. His account is consistent with last year’s exhaustive Senate committee report on CIA torture methods, which concluded that no actionable intelligence information came from the “enhanced interrogation” techniques used in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Slahi, a native of the North African nation of Mauritania, gives us a rare window into the Kafkaesque dilemma faced by a tortured detainee, who is assumed guilty by virtue of his very captivity.

“The problem,” Slahi writes, “is that you cannot just admit to something you haven’t done; you need to deliver the details, which you can’t when you haven’t done anything. It’s not just, ‘Yes, I did!’ No, it doesn’t work that way; you have to make up a complete story that makes sense to the dumbest dummies. One of the hardest things to do is to tell an untruthful story and maintain it, and that is exactly where I was stuck.”

In Hollywood films, torture is often portrayed as the infliction of physical pain. And while Slahi is subjected to a relentless onslaught of physical abuse — from being soaked in ice water to being forced to stand for hours on end in freezing cells — the most dehumanizing aspects of his indefinite detention at Guantánamo involve ritualized psychological terror. He is told, for instance, that his beloved mother from Mauritania has been captured and detained and that he would be sent to far worse places, such as Egypt or Israel, if he did not cooperate.

At one point, his interrogators stage an elaborate mock kidnapping — taking a shackled and hooded Slahi on a high-speed boat ride out to sea — to make it appear as if he is being transported to a faraway prison. During the ride, Slahi’s kidnappers force him to drink saltwater until he vomits and immerse him in ice cubes to hide the bruising from beatings.

As Slahi begins to confess things that not even the U.S. government believes he did, his captors give him a pillow — the first personal item of any kind he is allowed to have during his confinement. Slahi, deprived of sensory material, takes to reading the tag of the pillow over and over again in his isolated cell.

The shadowy reach of the U.S. government can be felt throughout the book, in the form of more than 2,500 black-mark redactions by government censors who pored over the text. Many of the redactions seem as arbitrary and bizarre as the torture described in the book. At one point, Slahi is moved to tears by a guard’s kind words — but the word “tears” is blacked out.

In 2010, a federal judge granted Slahi’s habeas corpus petition for release after finding no evidentiary basis for his confinement. An appeals court overturned the release order and Slahi, now 44, remains in the same cell where he wrote his diary in 2005.

(c)2015 Star Tribune (Minneapolis), Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.