A reading from the annals of American journalism:

The inescapable hurry of the press inevitably means a certain degree of superficiality. It is neither within our power nor our province to be ultimately profound. We write 365 days a year the first rough draft of history, and that is a very great task.

These words, spoken by Washington Post publisher Philip Graham in 1953, have aged well. Six decades later, we have more daily news, opinion, and analysis than ever, but profundity is still scarce. If that standard is too high for the first draft of history, what can we reasonably expect from the second?

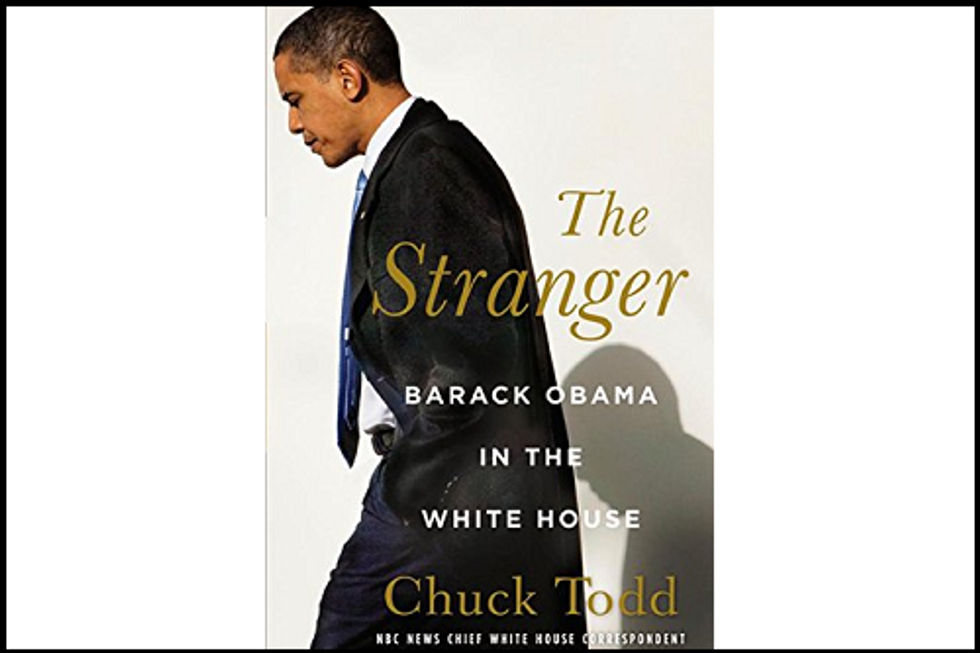

Chuck Todd’s The Stranger: Barack Obama in the White House raises this question with unusual force. Todd hosts Meet the Press, serves as NBC News’ political director, and was that network’s chief White House correspondent from 2008 to 2014. Few journalists are in better position to tell the inside story of Barack Obama and his presidency. Todd’s announced goal for The Stranger is to “bring readers behind the scenes to understand both who Barack Obama is and who he isn’t, what he strives to be and what he actually is.”

Todd does indeed bring readers behind the scenes, furnishing almost 500 pages of D.C. war stories, many of them media-centric, and most of them involving Obama. But Todd’s portrait of Obama is more problematic. Part of the problem is his book’s episodic structure. Most of the 19 chapters examine a specific challenge that Obama has faced in office: health care reform, Afghanistan, the 2010 elections, gays in the military, handling the Clintons, refuting the birthers, and so on. Each chapter reflects firsthand reporting and adds a drizzle of analysis. But the great issues of the day are set next to trifles like beads on a string, with little or no indication of their relative importance. It’s a difficult way to produce a portrait or even a cohesive narrative. As Todd plows through the crises, conflicts, and teapot tempests, I thought of Ben Hecht, who compared daily journalism to telling time by looking only at the minute hand of the clock.

What portrait of Obama we do have is furnished mostly through contrast. Joe Biden figures heavily and positively in Todd’s account, almost always as the president’s old-school liaison with a truculent Congress. Bill Clinton is the consummate retail politician, the kind Obama perversely refuses to become. The president’s other foils include Hillary Clinton and George W. Bush, but Todd returns again and again to The Man from Hope. Obama’s problems with Congress could be solved if only he, like President Clinton, persisted in winning over his enemies even as they try to pulverize him. Instead, Obama relies too much on logic and rationality in an irrational world. Worse, he “shows clear disdain for almost every institution that defines the Capitol.” As a consequence, Washington’s “governing culture” returns that disdain, and nothing is accomplished.

Todd’s description of Obama matches others in circulation, but here’s where checking the hour hand of the clock might be worthwhile. Yes, President Clinton cooperated with the GOP — for example, to deregulate Wall Street. In doing so, he helped enable the fraud and greed that eventually crashed the global economy. Working with the Republican Congress, Clinton also reduced the annual deficit, and like many in the Beltway, Todd blesses Obama’s efforts to do the same — even during a weak recovery, when austerity is precisely the wrong move for economic growth. Finally, Clinton helped the Republican Congress “end welfare as we have come to know it.” Todd thinks Obama could likewise work productively with the GOP on “entitlement reform”

Though Obama has long said he would like to revise the social safety net programs that suck up so much of the federal government’s money (an issue on which he could find common ground with Republicans), many Democrats, particularly the ones in leadership, have made it clear they have no intention of allowing benefit cuts.

These programs presumably include Social Security, which has its own funding stream, performs the job it’s supposed to do, and is popular with the American people. It seems never to occur to Todd that working with the GOP to cut benefits would hurt the vast majority of Americans, just as the bipartisan deregulation of Wall Street did. For him, spending cuts would demonstrate leadership, and that’s what matters.

Like many of his media colleagues, Todd also can’t resist false equivalencies. Both George W. Bush and Obama, he writes, early on addressed a crisis “by tackling something that, though tangentially related, didn’t share a direct relationship to the immediate concern.” Bush responded to 9/11 by invading Iraq, while Obama focused on health care reform instead of the recession. A better description might be that Bush manufactured a problem in Iraq whose remedy produced a catastrophe. In contrast, Obama addressed a real problem (health care) with mixed results, and passed an economic stimulus that was offset by spending cuts at the state and local level. Meanwhile, he tried to clean up Bush’s mess in Iraq and later approved a mission that killed Osama Bin Laden — an immediate concern by any definition.

If you like clichés and mixed metaphors with your false equivalencies, Todd won’t disappoint you:

There was no doubt that Republicans in Congress were doing everything they could to destroy the president’s agenda, but if Barack Obama wanted to glimpse the other great obstruction, he needed only to look into the mirror. Because while he didn’t have a willing dance partner, he seemed completely flummoxed by how to navigate these political waters and ask for a dance.

What Obama would see in the mirror, apparently, is an awkward teenager failing to navigate the political waters at the prom. (This is what the New York Times rather generously calls “utilitarian prose.”) But even if we disentangle Todd’s metaphors, the dance trope doesn’t work. Todd details the lengths to which Republicans now go to avoid contact with Obama for fear of attacks from their right. The girls in Todd’s metaphor wouldn’t dance with Obama under any circumstances; even being seen with him would end their social lives. Here and elsewhere, Todd implicitly equates Obama’s reluctance to perpetually court his adversaries with their reflexive refusal to engage him constructively.

By way of conclusion, Todd assesses Obama’s reputation:

[Obama’s] legacy in the long run may have bright prospects, but as it stands in the near future he will be a president whose potential wasn’t realized. He nudged the political spectrum to the left, without changing it. He began a recovery, without completing it. He passed major legislative initiatives by compromising some of the values he held dear.

As Todd notes, Obama likes policies (such as Romneycare) once favored by moderate Republicans. That’s what “the left” means in this paragraph. As for the idea of nudging a spectrum: Is that even possible? And how would Obama have completed the economic recovery? Certainly not by accommodating the GOP, whose austerity program was far more economically wrongheaded than his own. To realize his potential, Obama should have changed the political spectrum (whatever that means), completed the economic recovery with or without Congress, and built broad consensus for major reforms without compromising his values. This, ladies and gentlemen, is why Chuck Todd makes the big bucks.

Finally, there’s the matter of timing. One wonders why Todd would offer this portrait as Obama enters the final two years of his presidency — what Obama calls the fourth quarter, when “interesting stuff happens.” His recent initiatives on immigration reform, Cuba, and China support that remark. Todd’s assessment of Obama’s legacy is premature at best, even if his war stories are welcome.

Falling somewhere between rough draft and polished presidential history, The Stranger offers interesting and valuable information about Obama and his presidency but struggles to transcend the superficiality of daily journalism. For this reason, and despite its contributions, The Stranger doesn’t realize its potential.

Peter Richardson is the book review editor at The National Memo. His history of Ramparts magazine, A Bomb in Every Issue, was an Editors’ Choice at The New York Times and a Top Book of 2009 at Mother Jones. In 2013, he received the National Entertainment Journalism Award for Online Criticism. No Simple Highway, his cultural history of the Grateful Dead, is scheduled for January 2015.