The Government Really Did Fear A ‘Bowling Green Massacre’ — From A White Supremacist

Reprinted with permission from ProPublica. This story was co-published with The New York Times.

The year was 2012. The place was Bowling Green, Ohio. A federal raid had uncovered what the authorities feared were the makings of a massacre. There were 18 firearms, among them two AR–15 assault rifles, an AR–10 assault rifle, and a Remington Model 700 sniper rifle. There was body armor, too, and the authorities counted some 40,000 rounds of ammunition. An extremist had been arrested, and prosecutors suspected that he had been aiming to carry out a wide assortment of killings.

“This defendant, quite simply, was a well-funded, well-armed, and focused one-man army of racial and religious hate,” prosecutors said in a court filing.

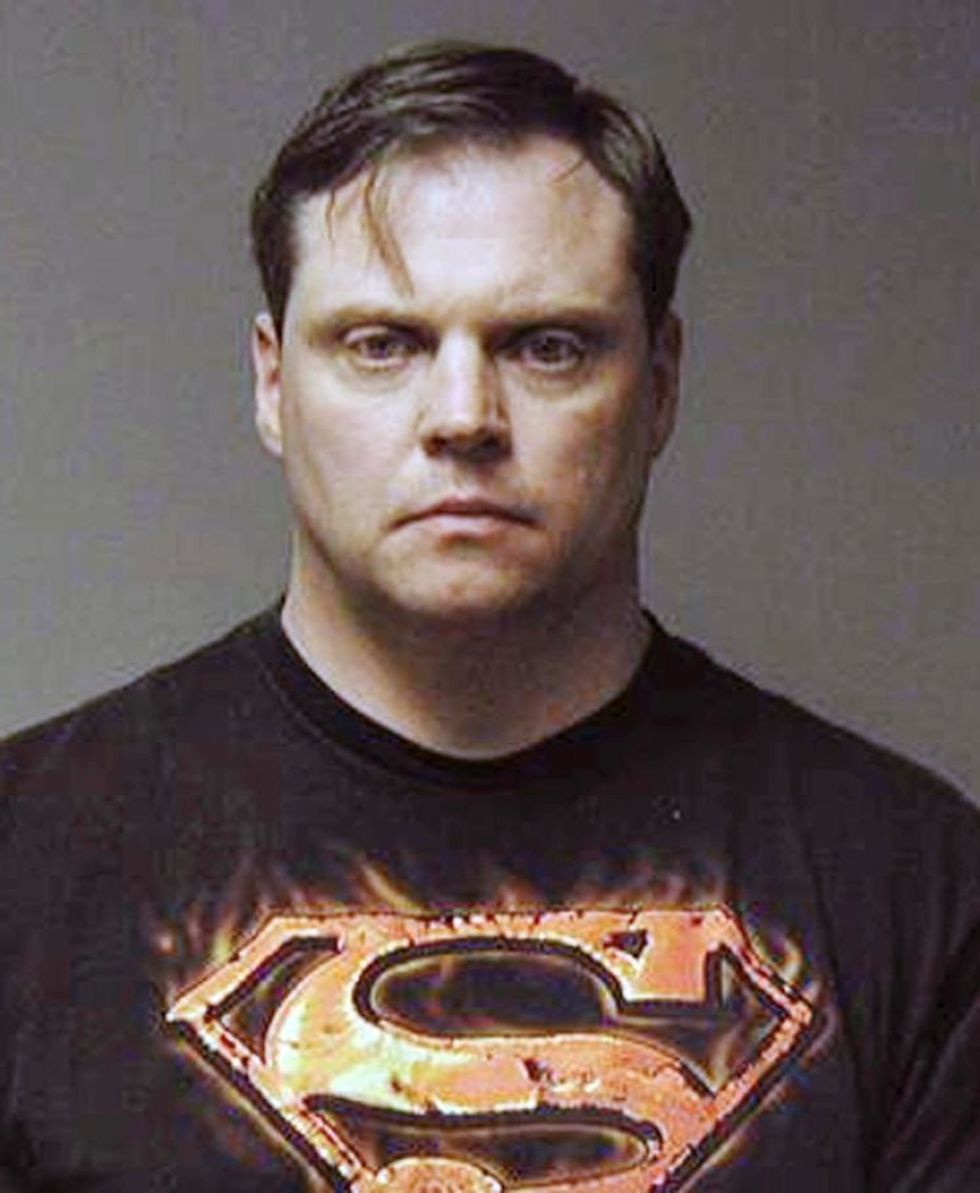

The man arrested and charged was Richard Schmidt, a middle-aged owner of a sports-memorabilia business at a mall in town. Prosecutors would later call him a white supremacist. His planned targets, federal authorities said, had been African-Americans and Jews. They’d found a list with the names and addresses of those to be assassinated, including the leaders of NAACP chapters in Michigan and Ohio.

But Schmidt wound up being sentenced to less than six years in prison, after a federal judge said prosecutors had failed to adequately establish that he was a political terrorist, and he is scheduled for release in February 2018. The foiling of what the government worried was a credible plan for mass murder gained little national attention.

For some concerned about America’s vulnerability to terrorism, the very real, mostly forgotten case of Richard Schmidt in Bowling Green, Ohio, deserves an important place in any debate about what is real and what is fake, what gets reported on by the news media and what doesn’t. Those deeply worried about domestic far-right terrorism believe United States authorities, across many administrations, have regularly underplayed the threat, and that the media has repeatedly underreported it. Perhaps we have become trapped in one view of what constitutes the terrorist threat, and as the case of Schmidt shows, that’s a problem.

The notion of a “Bowling Green massacre,” of course, has been in the news recently. Kellyanne Conway, a senior adviser to President Donald Trump, referred to it in justifying the president’s travel ban on people from seven predominantly Muslim countries. Conway had Bowling Green, Kentucky, in mind, but she eventually conceded there had been no massacre there. She meant, she said, to refer to the 2011 case of two Iraqi refugees who had moved to Kentucky and been convicted of trying to aid attacks on American military personnel in Iraq. One was sentenced to 40 years, the other to life in prison.

Her gaffe, accidental or intentional, prompted a mock vigil in New York and a flood of internet memes. The imaginary massacre now even has its own Wikipedia page.

On Monday, Trump made the provocative, unsubstantiated claim that the American media intentionally failed to cover acts of terrorism around the globe. “It’s gotten to a point where it’s not even being reported,” he said in a speech to military commanders. “And in many cases the very, very dishonest press doesn’t want to report it. They have their reasons, and you understand that.”

At the Southern Poverty Law Center, Ryan Lenz tracks racist and extreme-right terrorists. So far, he said, he’s seen little from the Trump administration to suggest it will make a priority of combating political violence carried out by American racist groups.

“It doesn’t seem at all like they are interested in pursuing extremists inspired by radical right ideologies,” said Lenz, who edits the organization’s HateWatch publication.

Indeed, Reuters reported last week that the Department of Homeland Security is planning to retool its Countering Violent Extremism program to focus solely on Islamic radicals. Government sources told the news agency the program would be rebranded as “Countering Islamic Extremism” or “Countering Radical Islamic Extremism,” and “would no longer target groups such as white supremacists who have also carried out bombings and shootings in the United States.”

It wouldn’t be the first time the Department of Homeland Security chose to look away. In 2009, Daryl Johnson, then an analyst with the department, drafted a study of right-wing radicals in the United States. Johnson saw a confluence of factors that might energize the movement and its threat: the historic election of an African-American president; rising rates of immigration; proposed gun control legislation; and a wave of military veterans returning to civilian life at a time of painful economic recession.

The report predicted an uptick in extremist activity, particularly within “the white supremacist and militia movements.”

Response to the document was swift and punishing. Conservative news outlets and Republican leaders condemned Johnson’s report as a work of “anti-military bigotry” and an attack on conservative opinion. Janet Napolitano, the head of Homeland Security at the time, retracted the report and closed Johnson’s office, the Extremism and Radicalization Branch.

Three years later, Richard Schmidt came to the attention of the federal government almost by accident. Schmidt had been suspected of trading in counterfeit NFL jerseys. Searching his home and store for fake goods, FBI agents discovered something far more sinister: a vast arsenal. A secret room attached to Schmidt’s shop “contained nothing but his rifles, ammunition, body armor, his writings, and a cot,” wrote prosecutors in a court document.

Beefy, thick-necked, standing 6-foot-4, and weighing about 250 pounds, Schmidt had spent years in the Army as an active-duty soldier and a reservist. His military service ended in 1989 when he got into a fight and shot three people, killing one of them, a man named Anthony Torres. As a result, Schmidt spent 13 years in prison on a manslaughter conviction and was legally barred from owning firearms.

After searching his property, the government came to believe he was involved with the National Alliance, a virulent and long-running extremist group, which was once among the nation’s most powerful white supremacist organizations. They also suspected him of an affiliation with the Vinlanders, a neo-Nazi skinhead gang.

Founded by William Pierce, who died in 2002, the National Alliance has long been linked to terrorism. Pierce, who started the group in 1970 and ran it for many years from a compound in West Virginia, wrote The Turner Diaries, an apocalyptic novel that basically lays out a blueprint for unleashing a white supremacist insurgency against the government. The novel was described by Timothy J. McVeigh as the inspiration for his bombing in 1995 of a federal office building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people.

FBI agents came to believe Schmidt had been planning his own string of racially motivated attacks on African-American and Jewish community leaders. The agents spread out across Ohio and Michigan to alert his apparent targets. “They had a notebook of information from Schmidt’s home,” recalled Scott Kaufman, the chief executive of the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Detroit. “Some of the items related specifically to our organization and staff — people’s names, locations, maps. It was certainly disturbing.”

In court, the defense lawyer Edward G. Bryan disputed the government’s portrayal of Schmidt, who was 47 at the time of his arrest. Bryan painted his client as a slightly eccentric survivalist who didn’t intend to “harm anyone, including those listed in written materials found within his property.”

The government saw it differently. Schmidt, prosecutors wrote in a sentencing memo filed in court, planned to assassinate “members of religious and cultural groups based only on their race, religion, and ethnicity.” His cache of weapons, added prosecutors, had only one purpose: to start a “race war.” Other court documents suggest that he planned to videotape his killing spree and email the video clips to his fellow white supremacists.

After pleading guilty to weapons and counterfeiting charges, Schmidt was sentenced to 71 months in federal prison by Judge Jack Zouhary in December 2013.

These days, Kaufman of the Jewish Federation in Detroit doesn’t think much about Schmidt. He’s got plenty of other things to worry about. “In the last two weeks in our community we’ve had two bomb scares,” as well as an incident involving spray-painted swastikas, he said. He’s noted a spike in anti-Semitic incidents over the past year.

“This whole thing is trending in the wrong direction,” he said.

IMAGE: Richard Schmidt / Department of Justice