During my school days, I used to enjoy taking standardized tests the way some people like doing crossword puzzles. To me, they were more rewarding than most of what went on at school. As an avid reader and an indifferent student, tests like the SAT were made for somebody like me—a bookworm who read fast enough to finish the exam early and who knew lots of vocabulary words he’d never heard spoken at home.

Perhaps accordingly, I’ve always found the recurring spasms of anxiety and outrage that accompany the College Board’s every adjustment in what used to be called the “Scholastic Aptitude Test” to be overblown and unpersuasive. So when I read a Washington Post column by a Princeton graduate referencing the SAT as a “hazy, horrible memory” and “the test from hell,” it’s hard not to suspect exaggeration. Most professional writers had high verbal scores.

I’m guessing Christine Emba did too.

Or maybe it’s because my other great pastime back then was sports. Playing ballgames, you learn pretty quickly how good you are, how good you’re not, and how to deal with it. I’ve always wondered if some of these stressed-out hothouse flowers would experience less SAT anxiety if instead of drilling with tutors, they’d spent more getting chosen in pickup games.

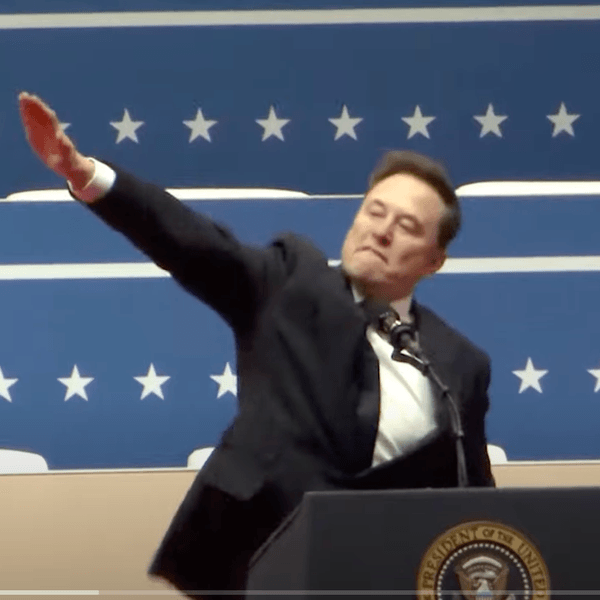

Indeed, one reason Americans love sports is their objectivity. You can’t bluff your way into Major League Baseball; no amount of Daddy’s money can put you in the NBA. So it’s good to remember, as Jonathan Wai, Matt Brown, and Christopher Chabris, a trio of education researchers, wrote regarding those Hollywood actresses and hedge fund managers who scammed their children’s way into elite colleges: They had to hire ringers to take the SAT. That is, “they had to fake intellectual ability—the one thing they could not buy.”

Grades, courses, recommendations, all these things can be purchased. But when it comes to college admissions, they write, “for every privileged student whose bad SAT score keeps them out, there is another student whose SAT helps get them in.”

I was one of those, although I never thought it made me a genius. The SATs measure verbal and mathematical facility, nothing else. For example, I have zero musical aptitude and couldn’t draw a recognizable human face to save my life.

The test said I had math aptitude; it remains theoretical.

For that matter, I had a childhood friend who could scarcely read (dyslexia, I suspect) but who had amazing mechanical ability. Steve was making lawnmower motor go-carts and repairing TV sets in junior high. School was torture for him, but post-Sputnik he made rockets in his father’s basement shop and fired them out of sight. He aced shop class; I did not.

Anyway, here’s the thing: nobody in our circle ever thought Steve was stupid. After I left for college, he moved out to California, where he became a successful contractor. I expect he hires the book work done.

Not everybody needs to go to an Ivy League college.

Which brings us to the latest coddling mechanism by the College Board, something called an “Environmental Context Dashboard,” purporting to measure with sociological exactitude the exact degree of privilege or deprivation in a student’s background. College admissions offices will be provided a number from 1 to 100 based upon things like real estate values, crime rates in the student’s neighborhood, average SAT scores in his or her high school, etc. Kind of like the “degree of difficulty” multiplier in competitive diving, I suppose.

Supposedly, the “adversity score,” as the Wall Street Journal dubbed it, will be kept confidential from test-takers—a stipulation that I doubt will survive the first lawsuit filed by a disappointed Princeton applicant.

Anyway, I’ve no clue what degree of difficulty would have been applied to my own scores. I never lived in a posh neighborhood, although my suburban high school sent lots of students to prestigious colleges. My mother, a high school graduate like my father, taught me to read at age three, and spent much of her life regretting it.

See, when other kids were working on Dick and Jane, I was reading novels by John R. Tunis and Albert Payson Terhune. (Baseball and dogs.) A bit later, I’d hide a flashlight under the covers to keep reading my Book of Knowledge encyclopedia after lights-out.

My mother feared I’d go blind. Instead, I went off to Rutgers, the state university, which sent me an admissions letter basically saying that given my SAT scores, my high school grades were a disgrace and that I’d better wise up. So I did, because I couldn’t take my hard-working parents’ money and flunk out.

However, I’ve never believed that my facility with standardized tests made me anybody special. And I also think that many Americans’ obsession with sending their children to “prestigious” high-dollar colleges verges upon mania.

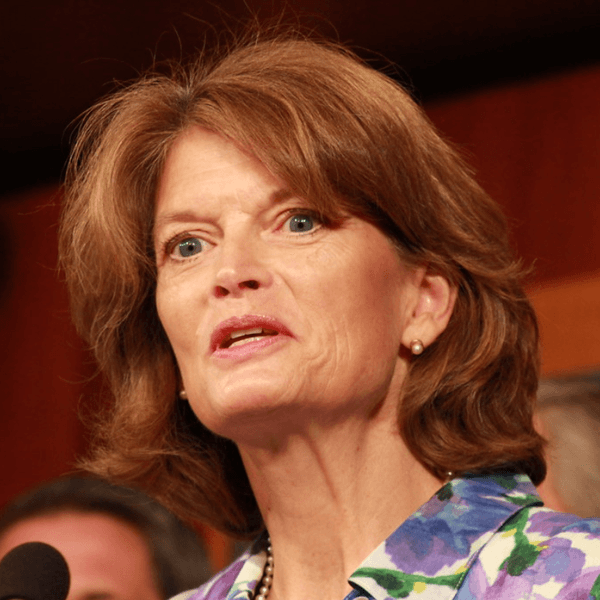

IMAGE: Lori Loughlin, one of the actors indicted in the college admissions scandal, and her daughters.