Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney

For those puzzled by my headline: Back in 1986 The New Republicchallenged its readers to come up with a headline more boring than “Worthwhile Canadian Initiative,” the title of a New York Times op-ed by Flora Lewis. They couldn’t. Canada, you see, was considered inherently boring.

As I wrote a couple of months ago, economists have never considered Canada boring: It has often been a laboratory for distinctive policies. But now it’s definitely not boring: Canada, which will hold a snap election next month, seems poised to deliver a huge setback to Donald Trump’s foreign ambitions, one that may inspire much of the world — including many people in the United States — to stand up to the MAGA power grab.

So this seems like a good time to look north and see what we can learn. Here are three observations inspired by Canada that seem highly relevant to the United States.

Other countries are real

I don’t know what set Trump off on Canada, what made him think that it would be a good idea to start talking about annexation. Presumably, though, he expected Canadians to act like, say, university presidents, and immediately submit to his threats.

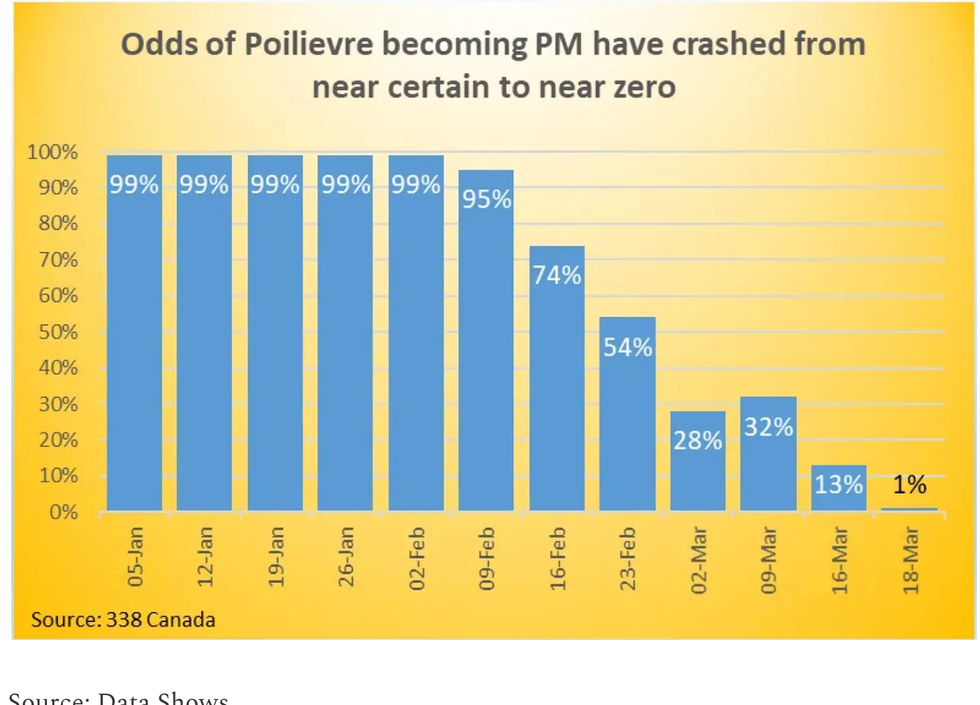

What he actually did was to rally Canadians against MAGA. Just two months ago Canada’s governing Liberals seemed set for a historic collapse, with Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre the all-but-inevitable next prime minister. Now, if the polls are to be believed, Poilievre — who has been trying to escape his image as a Canadian Trump, but apparently not successfully — is effectively out of the running:

I won’t count my poutine until it’s served, but it does seem as if Trump’s bullying has not only failed but backfired spectacularly. (And, arguably, saved Canada; all indications are that Poilievre is a real piece of work.) But why?

Much of this is on Trump, who always expects others to grovel on command. But it also reflects a general limitation of the American imagination: we tend to have a hard time accepting that other countries are real, that they have their own histories and feel strong national pride. Canada, in particular, arguably defined itself as a nation in the 19th century by its determination not to be absorbed by the United States.

In fact, there are almost eerie parallels between some of those old confrontations and current events. The 1890 McKinley tariff, of which Trump speaks with such admiration, was in part intended to pressure Canada into joining the U.S.. Instead, it inspired a backlash: Canada imposed high reciprocal tariffs, sought to strengthen economic linkages between its own provinces, and built a closer economic relationship with Britain.Sure enough, Mark Carney, the current and probably continuing Canadian prime minister, has emphasized removing remaining obstacles to interprovincial trade and seems to be seeking closer ties to Europe.

Trump may expect submission; he’s actually getting “elbows up.”

Time and chance happeneth to us all

Why, but for the grace of Donald Trump, was the Liberal Party headed for electoral catastrophe? There were specific policy issues like the nation’s carbon tax and Justin Trudeau’s personal unpopularity, but surely the main reason was a continuation of the factors that made 2024 a graveyard for incumbents everywhere, especially continuing voter anger about the inflation surge of 2021-22.

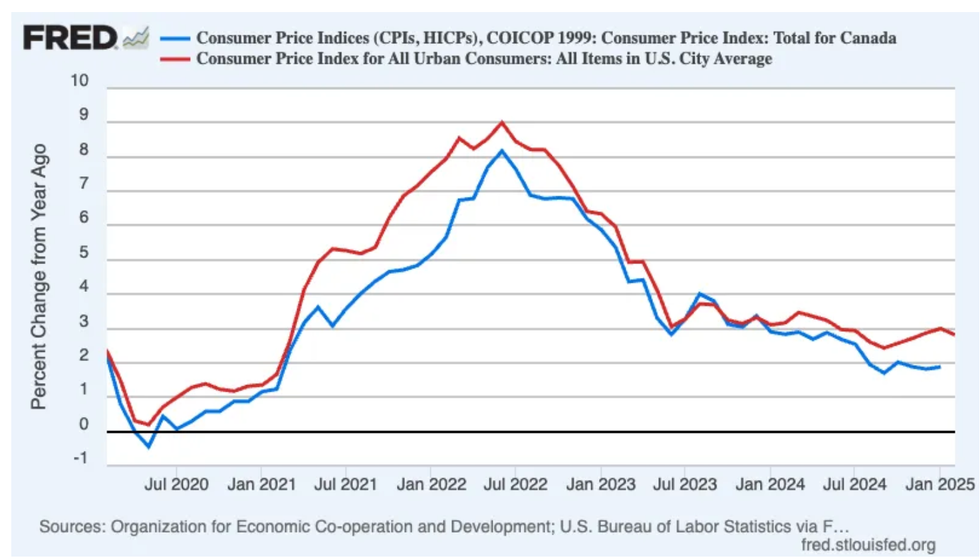

Some of us tried to point out that the very universality of the inflation surge meant that it couldn’t be attributed to the policies of any one country’s government. If Bidenomics was responsible for U.S. inflation, why did Europe experience almost the same cumulative rise in prices that we did? But there was never much chance of that argument getting traction in the United States, where we have a hard time realizing that other countries exist.

The Canadians, however, definitely know that we exist, and you might think that public anger over inflation would have been assuaged by the recognition that Canada’s inflation very closely tracked inflation south of the border:

But no, Canadian voters were prepared to punish the incumbent party anyway for just happening to hold power in a difficult time. The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet electoral victory to parties with good policies; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

Life is about more than GDP

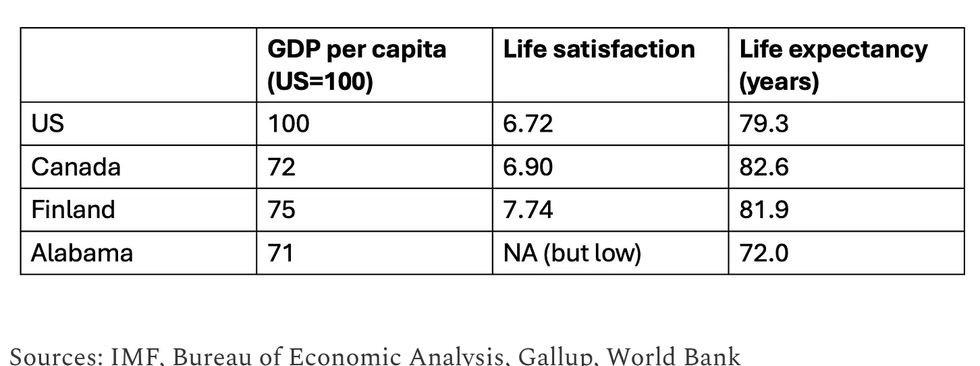

Canada’s inflation experience looks a lot like ours, but in other ways Canada has clearly underperformed. In particular, it has had weak productivity growth, which has left it substantially poorer than the U.S.. Canada, The Economist declared in a much-quoted article, is now poorer than Alabama, as measured by GDP per capita.

That’s not quite what my numbers say, but close. Yet Canada doesn’t look like Alabama; it doesn’t feel like Alabama; and by any measure other than GDP it isn’t anything like Alabama. Here’s GDP per capita along with a widely used measure of life satisfaction, the same one often cited when pointing out how happy the Nordic countries seem to be, and life expectancy at birth:

So yes, Canada’s GDP per capita is comparable to that of very poor U.S. states. So is per capita GDP in Finland, generally considered the world’s happiest nation. But Canadians appear, on average, to be more satisfied with their lives than we are, although not at Nordic levels. We don’t have a comparable number for Alabama, but surveys consistently show it as one of our least happy states.

Part of the explanation for this discrepancy, no doubt, is that so much of U.S. national income accrues to a small number of wealthy people; inequality in Canada is much lower.

And I don’t know about you, but I believe that one important contributor to the quality of life is not being dead, something Canadians are pretty good at; on average, they live more than a decade longer than residents of Alabama.

The general point here is that while GDP is a very useful measure, and is generally correlated with the quality of life, it’s not the only thing that matters. And the more specific point is that Canada, which among other things has universal health care, has some good reasons beyond national pride not to become the 51st state.

So Canada isn’t boring now, and it never was. As I said, try looking north; you might learn something.

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former professor at MIT and Princeton who now teaches at the City University of New York's Graduate Center. From 2000 to 2024, he wrote a column for The New York Times. Please consider subscribing to his Substack, where he now posts almost every day.

Reprinted with permission from Paul Krugman.

- Kremlin Excited By Trump's Imperialism Toward Greenland, Canada And Panama ›

- New Quinnipiac Poll Shows Majority Reject Trump On Key Issues ›

- Trump Escalates Threats Against Greenland, Panama And Canada ›

- Will Trump Backpedal As Tariffs Tank Our Economy? ›