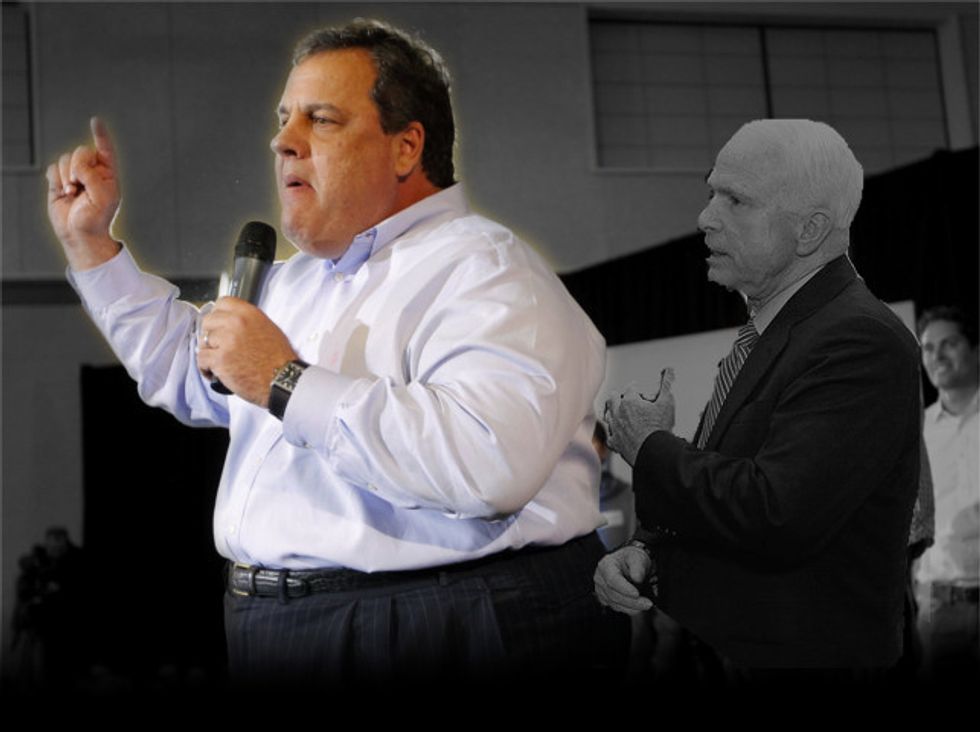

It’s no surprise that Chris Christie has adopted the straight-talk strategy that carried John McCain to a huge upset victory over George W. Bush in the 2000 New Hampshire primary and helped him win the Republican presidential nomination in 2008. It’s a natural fit given the New Jersey governor’s blunt, outspoken personality.

Yet McCain was in first or second place in polls of New Hampshire at this point both times he ran. Christie is in single digits, and as far back as ninth in one poll of the large Republican pack.

There’s a reason it’s not working. There’s no way to break this gently: Chris Christie is no John McCain.

In McCain, the Arizona senator, you had a bona fide Vietnam War hero who had spent more than five years as a prisoner of war. You had a presidential candidate whose candor on the 2000 trail was startling, sometimes charming and occasionally quite personal.

When a voter in rural New Hampshire complained about substandard medical facilities, McCain said that was the price for the voter’s choice to live in a gorgeous setting instead of a more populated area. When another New Hampshire voter worried aloud about whether his child would be able to get a factory job, McCain advised him to aim higher for his child. He undercut his own anti-abortion position when a reporter asked if he’d forbid an abortion for his teenage daughter if she became pregnant — saying he’d discourage that but the final decision would be hers. When the predictable furor erupted, he did not kick the press off the bus.

With McCain, you also had politician who was publicly and continually remorseful about his role in a campaign finance scandal, who then became passionate about breaking the connection between money and influence. This defining ethics challenge came in 1987. That’s the year McCain and four other senators asked federal regulators to drop charges against the Lincoln Savings and Loan chaired by Charles Keating Jr., a donor to all their campaigns.

Taxpayers were on the hook for a $3 billion bailout when Lincoln S&L collapsed in 1989. McCain called his intervention on behalf of Keating “the worst mistake of my life.” A decade later he made campaign finance reform the centerpiece of his first presidential campaign.

Bridgegate has been Christie’s defining ethics challenge. The massively disruptive four-day traffic jam on the Fort Lee approach to the George Washington Bridge was engineered by his aides in 2013 as political revenge against a Democratic mayor who did not support him for re-election that year. For nearly a week, their fake “traffic study” turned 30-minute commutes into three and four hours. The New York Times offered a sampling of who was trapped in the crippling gridlock: first responders in police cars and ambulances; buses of kids headed to the first day of school; a longtime unemployed man who was late for his first day at a new job, and a woman who couldn’t reach the hospital in time for her husband’s stem-cell transplant.

Christie said he had been “blindsided” by the plot. He said he was embarrassed and humiliated and apologized to “the people of New Jersey” and “the people of Fort Lee.” He also denied creating an atmosphere that led to such behavior and maintained that “I am not a bully.” If he had followed the McCain model, Christie would have then become a highly visible national advocate for good government, political civility and excellence in public service. He might have started an organization to that effect, or joined one. Alternatively, perhaps he would have launched or lent his name to an anti-bullying organization.

Unlike McCain, Christie does not have a heroic personal biography to cushion problems. He does have a long, mixed, and controversial record as governor. He also has a long trail of viral videos that show him insulting and shouting at people who disagree with his policies. That image was a boon for his popularity and his fundraising for his party. He used to revel in it. Now, not so much. Now he is trying to morph into a policy truthteller on entitlements, taxes, and national security.

“Real. Honest. Direct. Tell It Like It Is.” According to National Journal, that’s the banner that advertised Christie’s recent appearance at The Village Trestle tavern in Goffstown, New Hampshire. But there’s a difference between confrontational straight talk and the McCain 2000 brand of straight talk. Christie, belatedly realizing that the first kind is not presidential, is trying to transition to the latter. But his problems go deeper than that, as do his differences from McCain.

Follow Jill Lawrence on Twitter @JillDLawrence. To find out more about Jill Lawrence and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

Image: The National Memo