Critic’s Notebook: Virginia TV Shooting Sparks A Debate Over Viewing Of Footage

By Mary McNamara, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

To watch or not to watch.

Early Wednesday morning, reporter Alison Parker and cameraman Adam Ward were shot to death during a live interview for WDBJ-TV, a CBS affiliate based in Roanoke, Va. In less than an hour, clips of the event were on YouTube.

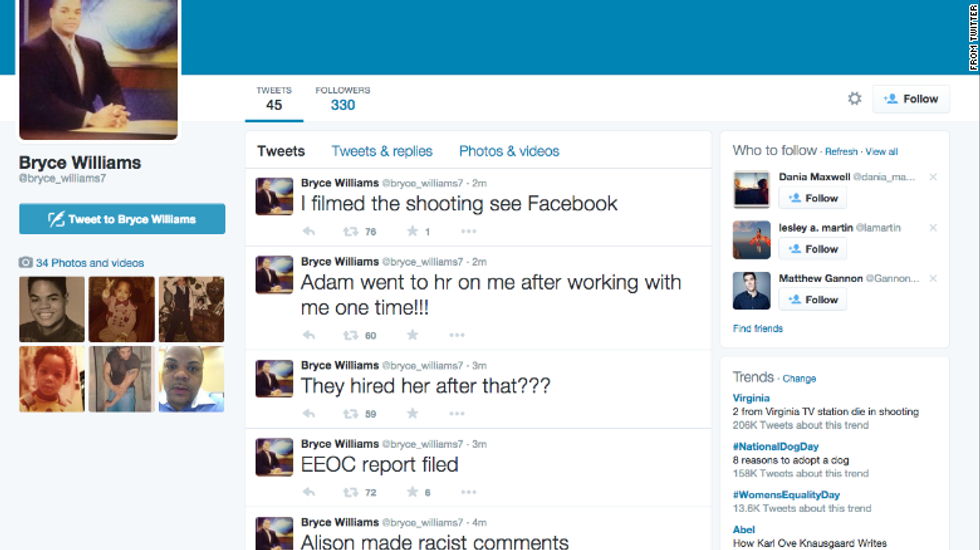

It soon developed that the suspected shooter, Vester Flanagan, a former reporter for WDBJ, had recorded the shooting himself, posted it on Facebook and then tweeted about it using his on-air name, Bryce Williams. Flanagan shot himself while being chased by police and later died.

The Twitter and Facebook accounts were quickly suspended, and YouTube took down the videos, but the disturbing images continued to circulate, prompting an equally widespread “Don’t Watch” campaign.

At best, some said, watching or sharing the footage was an endorsement of a media culture run amok, proof that the medium has indeed become the message _ people will now literally do anything to be on television.

At worst, it made us complicit in the killings themselves.

Either way, if we watched the brief tragic clips of the attack on Parker and Ward, or the chilling footage taken by Flanagan just before he began shooting, somehow Flanagan would “win.”

As if Flanagan were powerful enough to define our reactions to his crime or if any of those reactions were more important than the fact and nature of murder. As if news were suddenly beholden to feelings of gentility and any medium should be blamed for insane people attempting to leverage it for their own dissociated ends.

No doubt, the admonishments not to watch began with good intentions. When something terrible happens, many of us want to do something, to help in some way; it is the very best of human nature to offer aid of every sort as quickly as we can. Many, no doubt, refused to watch the videos (which did not show the actual deaths) out of respect for Parker, Ward and their families.

Others, however, quickly made it into a litmus test of something larger. “Murder is not entertainment” was a leitmotif of early commentary, as was the notion that Flanagan’s use of Twitter and Facebook illuminated the dark side of the digital age — technology has not only made it possible for someone to record the murder he is committing even as he commits it, some seem to think it has created an environment in which infamy is as desirable as fame.

None of which is either helpful or respectful.

Obviously murder is not entertainment, and it’s difficult to believe that anyone would be viewing or sharing the videos for entertainment’s sake. News outlets did not show the space shuttle Challenger explode repeatedly on a minute-by-minute basis, or the Twin Towers fall over and over again, for entertainment’s sake.

We do not watch news reports in which police brutalize teenagers or armies level villages for entertainment’s sake. We watch to see what happened. We watch because no amount of aftermath reporting or narrative reconstruction captures an event with more power and clarity than video footage.

We watch to remind ourselves that whatever our own reality may be, it is not the totality of human experience.

Certainly the murder of two journalists on live television will get more coverage than most other workplace murders, but the medium is not the message; the murders are the message. And the coverage does not signal an increased capitulation to the desires of the murderer.

Since civilization began, a certain subset of criminal has wanted attention for its crimes. Serial killers from Jack the Ripper to Son of Sam taunted police and sent missives to the newspapers. Bonnie and Clyde posed with their guns. John Wilkes Booth killed Abraham Lincoln in a theater before jumping onto the stage yelling “Sic semper tyrannis” (“Thus ever to tyrants”) and, by many accounts, was inconsolable by his portrayal in the press.

On Wednesday morning, YouTube and various media outlets, including the Los Angeles Times, made decisions on whether to make the videos available (the Times decided to post a clip that stops before the shooting). But to suggest that we ought to ignore horrific events out of fear that acknowledgment will fulfill a killer’s wish is not just absurd, it’s agreeing to adopt a murderer’s way of thinking.

Notoriety is not the same as fame no matter what a psychopath might think; watching or sharing the image of a terrible thing is not an endorsement of its occurrence.

Though we do now go on Jack the Ripper tours and celebrate the romance of Bonnie and Clyde.

And that is one very good reason to watch the videos, upsetting as the experience may be. Alison Parker and Adam Ward were killed, as so many people have been killed in this country, for no reason.

The random, senseless horror of their deaths — one minute Parker is doing her job, the next minute running for her life — should remind us that murder, which remains the No. 1 narrative arc in television drama, is not entertainment, that real killers are not fascinating creatures of tortured back story and twisted mythology. It should stop us in our tracks with the knowledge we are all vulnerable to random gun violence and that threats and signs of stalking should be taken seriously.

Most important, their deaths should remind us that every act of violence, every murder, occurs in moments of disjointed horror. Just as images of police brutality against black Americans recently reignited protest and investigations, the tragic last minutes of these lives should prompt as many serious conversations as prayers. About guns and mental illness, about safety in the workplace and whatever other issues come to light as the story evolves.

Not everything that occurs on television or social media is there for our enjoyment, and when the unacceptable or the outrageous occurs, we should draw as many eyeballs to it as we can. When we’re too afraid to see what violence really looks like, or too worried that our horror will encourage it, that’s when we’ll know the barbarians have won.

Photo: Live-tweeting the aftermath of his ramapage, Vester Flanagan/Bryce Williams maximized his attack for maximum exposure, wounding journalists of all stripes in the process. CNN/Twitter