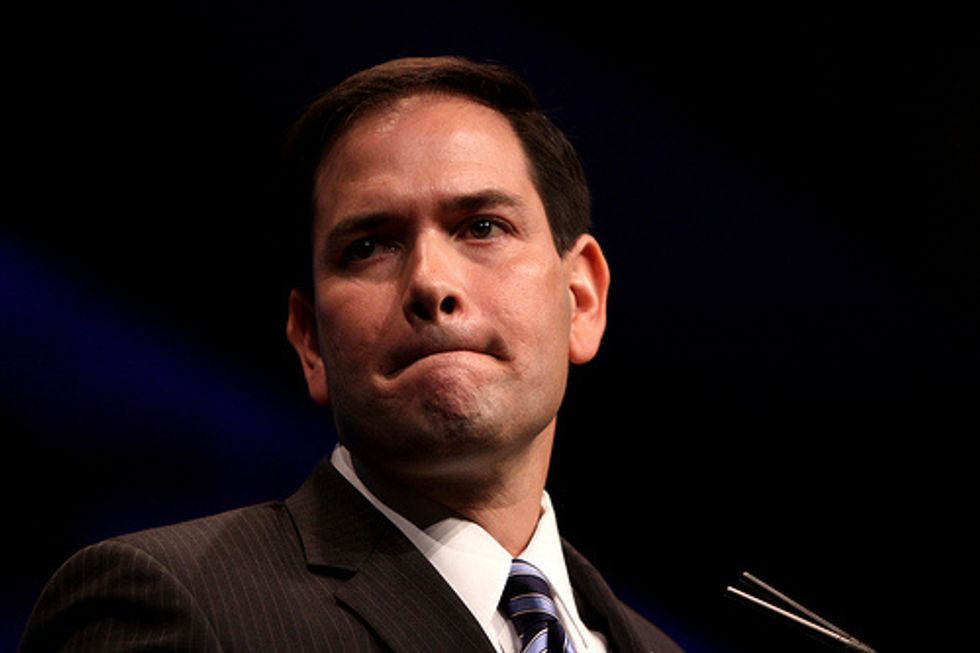

As Cuba Policy Moves Forward, Chief Critic Rubio Faces Stiff Odds Reversing It

By Chris Adams, McClatchy Washington Bureau (TNS)

WASHINGTON — In December, just hours after the White House abruptly changed course in the nation’s relationship with Cuba, Senator Marco Rubio laid down his marker.

“I intend to use every tool at our disposal in the majority to unravel as many of these changes as possible,” he said Dec. 17.

It’s now February — and despite congressional hearings and ongoing pressure on the administration, it’s not clear that Rubio and other opponents can undo what the president already did.

Rubio is perhaps the nation’s most prominent lawmaker on the Cuba issue. He’s a Cuban-American, a member of the Senate’s Republican majority and a potential presidential candidate. And he represents Florida, Cuba’s closest U.S. neighbor.

But according to Cuba experts, Rubio might have little ability to reverse Obama’s changes. And Rubio might have realized that.

That doesn’t mean Congress — and Rubio — can’t curtail the administration’s long-term plans. Congress clearly has authority over some aspects of the new Cuba policy, and congressional leaders beyond Rubio are skeptical of the president’s plans.

For his part, Rubio is letting the administration make its case — and also watching as Cuba makes demands that he said could make normalization untenable.

In an interview with McClatchy this week, Rubio said President Barack Obama has “exceeded his authority” with already-announced moves.

“I think many of the changes that he’s made run counter to existing legislation, which I believe makes it illegal,” Rubio said. “We’ve made that case, but obviously this is a case we want to prove. But ultimately it’s going to wind up in the court system.”

Those changes really are just the first step in the Cuban opening. Up next will be the establishment of an embassy in Havana, as well as the confirmation of an ambassador.

Asked whether there were enough votes in the Senate to deny confirmation to an ambassador, Rubio said, “Well, there are multiple ways to stop an ambassador nomination, and I reserve the right to use all of them. … I can tell you for certain that no matter who they nominate I will not be supportive of and will do everything I can to try to stop the nomination of an ambassador to an embassy that’s not a real embassy.”

The opening to Cuba is a complicated, multipronged effort. Already, the Treasury and Commerce departments have relaxed rules on some travel to Cuba, loosened restrictions on financial transactions between the United States and the island nation, and allowed for U.S. exports of certain products.

Rubio said some of those changes — such as increased telecommunications exports to Cuba — are specifically prohibited under current statutes and will not withstand legal challenges.

The White House disagreed. National Security Council spokesman Patrick Ventrell said that all changes were “looked at closely by administration lawyers and all actions were taken in the context of what could legally be done.”

According to experts on Cuba, stopping the actions the administration already has taken will be difficult, even with the Republicans in control of both sides of Congress.

“I think he’s in a bit of a bind,” said Phil Peters, president of the Cuba Research Center in Alexandria, Va. “I think he knows there’s not a legislative means to reverse what President Obama did.”

Rubio might be “planting a flag,” Peters added. “But in terms of action, I don’t think there’s anything he can do about it. President Obama acted clearly within his authority, and Congress can’t stop it.”

Last week, Rubio kicked off a trio of hearings — one in the Senate, two in the House of Representatives — in which opponents of the president’s plans laid out a case that the Obama administration was taken advantage of in negotiating its new policy. Rubio emphasized ongoing human rights abuses and political detentions on the island, as well as demands Cuban President Raul Castro has made as a condition for normalization.

Rubio’s hearing, experts said, helped frame the upcoming debate and could slow the administration’s plans.

“There was this level of irrational exuberance from proponents of the new policy, but Congress hadn’t had a say yet,” said Jason I. Poblete, a former Republican congressional staffer and an international regulatory lawyer with Poblete Tamargo LLP who supports the sanctions on Cuba but said he has been critical of both parties and prior administrations for their Cuba policies. “Now they are having a say.”

But having a say and reversing the policy are two different things — although Rubio will have an outsized role in the debate.

“People take what he has to say very seriously,” said Darrell M. West, vice president and director of governance studies at the Brookings Institution, a Washington think tank.

But the president has substantial executive power on his side. “He can open an embassy, he can liberalize travel restrictions, he can increase the amount of money that people living in America can send to Cuba,” West said. “There’s very little Senator Rubio can do about those things.”

Rubio “has the ability to stop the parts of the initiative that require congressional approval, like ending the embargo,” West said. “What he can’t block is opening an embassy.”

Beyond that are the big issues of freeing travel between the two countries and ending the embargo that has cut off Cuba from most trade with the United States. Legislation already has been introduced in Congress to accomplish both of those goals, though experts say Rubio and his allies have significant ability to sway the debate.

In an interview with the CBS News program 60 Minutes, House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) expressed opposition to the president’s plans, and Boehner was skeptical that the most ambitious of them — such as repealing the trade embargo with Cuba — would go anywhere. Asked whether the trade embargo would stay in place, Boehner said, “I would think so.”

Carl Meacham, a former senior Republican aide on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee who’s now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank, said that while support for the trade embargo is on the decline nationally, Rubio’s position as a voice for the Cuban exile community means its voice will be heard. A recent national poll by the Pew Research Center found two-thirds of respondents favored ending the embargo.

But whether the voice of the Cuban-American community will steer enough votes in Congress is unclear. Democrats are generally unified in a pro-change position — with at least one major, influential detractor in Senator Robert Menendez of New Jersey — while Republicans are more fractured, Meacham said.

The ultimate level of support that Rubio can expect for his position is hard to pin down, thanks to libertarian-leaning Republicans and those from agriculture states that would benefit from new markets.

“I really think Republicans are split on this issue,” Meacham said. “And those Republicans who support the president’s decision on this should not be ignored.”

Of all the potential changes to the relationship with Cuba, Meacham said Obama is able to change one-third of them on his own. The other two-thirds fall under the jurisdiction of Congress.

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr