For a man who lost so much — his freedom, his homeland and nearly his life — to Fidel Castro, my friend Juan Roque is extraordinarily unmoved by the tyrant’s death.

But that’s Roque’s hallmark: steady vision, calm spirit. It’s a standpoint that more people would be wise to adopt, especially now, as interested parties wait out this uncertain time between Fidel Castro’s death and the possible reversal of the U.S. rapprochement with Cuba under the incoming Trump administration.

Of all the voices chiming in on Castro’s death, Roque’s was the one I sought. We met years ago, when he was an advertising executive at The Kansas City Star. He’s mostly retired now, a grandfather of five living in a suburb of Kansas City.

At 16, Roque was a freedom fighter. He was a youngster brassy enough to alter the birthdate on his passport, convincing the CIA that he was old enough to fight in the Bay of Pigs invasion. He wasn’t, but our intelligence agents didn’t figure it out until it was too late.

Roque was dropped off, along with 1,400 other Cuban exiles, by boat near Cuba. They made it ashore and fought for three days, vastly outnumbered by Castro’s troops. More than 100 of the freedom fighters died before they ran out of ammunition.

Roque, thinking like an indestructible teenager, believed that he could swim 50 miles through shark-infested waters and reach safety. He tried but was captured. He spent the next 20 months in a Cuban jail, subsisting on noodles, bread and water.

The only times he got depressed was when he “made the mistake” of looking out the window and wondering if he’d spend the rest of his life imprisoned.

His mother, part of the underground resistance to Castro, was held in a Cuban jail at the same time. She’d been captured about eight months after sending her son and a daughter to the U.S., not knowing that her son would figure out a way to return. She’d spend 13 years in a Cuban prison.

His stepfather, who had been an adviser to the dictator Castro overthrew, Fulgencio Batista, was also jailed, for eight years. Both parents eventually made it to the United States and are now deceased.

“Nothing good happened to us as a result of Fidel Castro coming to power,” Roque told me. Still, he has long been refreshingly honest about U.S./Cuba relations, despite all that happened to him and his family.

Hatred of Castro can make people lose perspective. It’s one reason why so many, including some who have the ear of President-elect Donald Trump, continue to press for maintaining the embargo. Never mind that the economic blockade accomplished nothing to budge Castro from power — and did much to harm the Cuban people.

It’s a failed policy, although some still mistakenly cast it as a principled stand.

Roque has long favored lifting the embargo, trying to engage carefully, while remaining fully aware of the ongoing humanitarian sins of both Castro brothers. Raul Castro has been in power for nearly a decade now, so the death of Fidel is not the watershed some are celebrating.

“What can possibly happen?” Roque asked. “The Communist Party is still in control.”

Raul is 85 and set to retire from the presidency Feb. 24, 2018. Which is a reason why Roque is a patient man.

At a mere stroke of a pen, President Trump could reverse the executive orders Barack Obama has used to weave connections between the U.S. and Cuba. Those include the permission for businesses to import some Cuban goods, the relaxed regulations on what U.S. travelers can bring back from the island, an opening for U.S. interests to manage hotels in Cuba and for U.S. businesses and individuals to have bank accounts there.

The capitalism genie is out of the bottle. U.S. business interests will not willingly retreat from pursuing opportunities in Cuba.

In fact, the pace of rapprochement did not pause after Castro’s death, not even for his funeral. Two days after his last breath, as Castro’s ashes were ceremoniously making their way across Cuba, Havana was added as yet another Cuban destination reachable by scheduled commercial flights from a number of major U.S. cities.

Eventually, Roque might make a trip back to Cuba himself. He’d like for his beloved wife to see the island. But otherwise, he says, Cuba elicits sadness for him.

Before the revolution, Cuba was prosperous, with a growing middle class, Roque reflects. Castro destroyed that, but Roque refuses to waste the energy mourning it, adding philosophically, “You cannot go through life like that.”

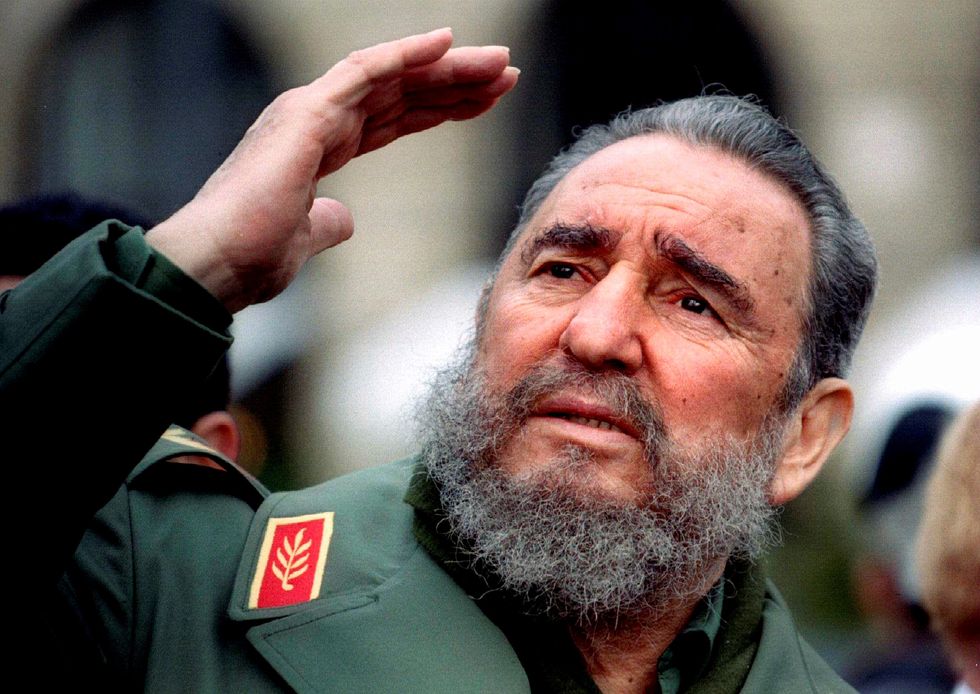

IMAGE: Cuba’s President Fidel Castro gestures during a tour of Paris in this March 15, 1995 file photo. REUTERS/Charles Platiau/Files