Reprinted with permission from Independent Media Institute.

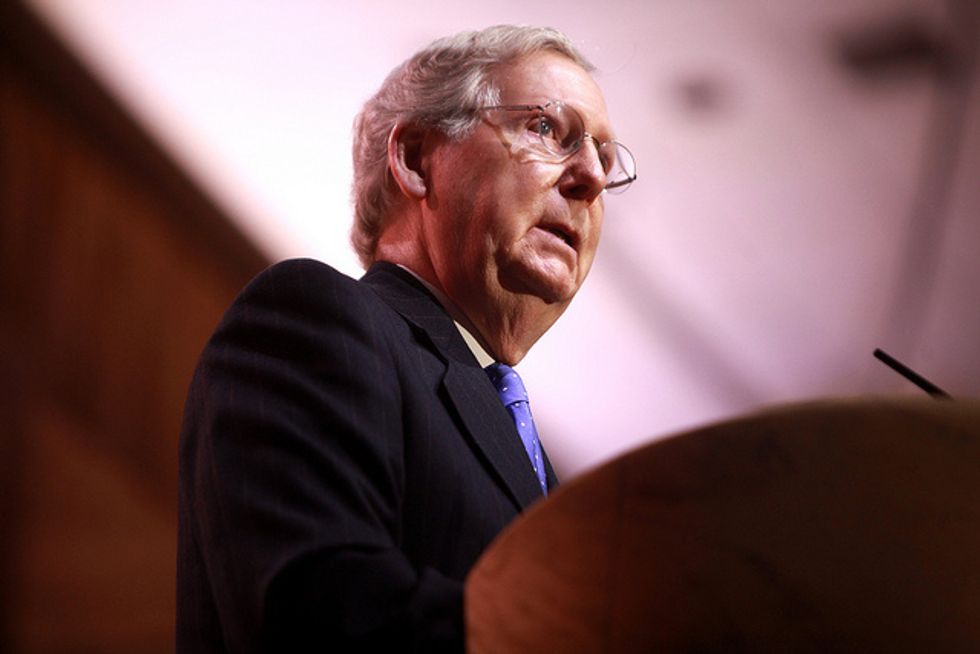

Prospects for a major federal sentencing reform bill brightened on Wednesday with President Trump’s announcement that he would support the effort, but by week’s end, those prospects dimmed abruptly as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) told the president he wouldn’t bring the bill to a floor vote this year.

The bill is known as the First Step Act. The House passed a version of this in spring, but the House version was limited to reforms on the “back end,” such as slightly increasing good time credits for federal prisoners and providing higher levels of reentry and rehabilitation services.

The Senate bill crafted by a handful of key senators and pushed hard by presidential son-in-law Jared Kushner incorporates the language of the House bill, but also adds actual sentencing reforms. Under the Senate bill:

Thousands of prisoners sentenced for crack cocaine offenses before August 2010 (the date of the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced, but did not eliminate sentencing disparities) would get the chance to petition for a reduced sentence.

Mandatory minimum sentences for some drug offenses would be lowered.

Life sentences for drug offenders with three convictions (“three strikes”) would be reduced to 25 years.

Even though the bill has been a top priority of Kushner’s and had the support of numerous national law enforcement groups and conservative criminal justice groups, as well as the support of key Democrats, such as Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL), McConnell told Trump at a White House meeting Thursday that there wasn’t enough time in the lame-duck session to take it up.

“McConnell said he didn’t have the time, that’s his way of saying this isn’t going to happen,” said Michael Collins, interim director of the Drug Policy Alliance’s (DPA) Office of National Affairs. “McConnell was a roadblock under Obama and he’s a roadblock now. He likes to hide behind the process but I think he just doesn’t like or care about this issue.”

McConnell’s move upset what should have been a done deal, said Collins.

“Once First Step passed the House, some key figures on the Senate side, such as Sens. Durbin and Grassley, said it wouldn’t move without sentencing reform, and then Kushner facilitated negotiations between the Senate and the White House and they reached broad agreement this summer,” he recounted.

“Then the question was can we get this to the floor? McConnell sat down with Grassley and Durbin and said after the elections, and Trump agreed with that,” Collins continued. “The idea was that if Trump would get on board, McConnell would hold a vote, would whip a vote. He wanted 60 votes; there are 60 votes. Then McConnell said the Senate has a lot to do. At the end of the day, it’s up to McConnell. When Trump endorsed, people thought it would move McConnell, but he just poured cold water on it.”

That means sentencing reform is almost certainly dead in this Congress. And as long as Mitch McConnell remains Senate Majority Leader, he will be an impediment to reform.

“McConnell is the obstacle—it’s not Tom Cotton (R-AR) or Jeff Sessions—it’s McConnell, and he’s going to be there next year and the year after that,” said Collins. “He is the prime obstacle to criminal justice reform, even though a lot of groups on the right are in favor of this. Since he isn’t going to listen to us, it’s going to be up to them to figure this out.”

“If McConnell doesn’t prioritize this, it doesn’t happen,” said Kara Gotsch, director of strategic initiatives for the Sentencing Project, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group. That’s a shame, she said, because “I’m optimistic both parties would support this if they got the chance.”

But now it doesn’t look like they will get that chance. That’s the downside. But there is a possible upside: Failure to pass limited criminal justice reform this year may lead to a bill next year that goes further than limited sentencing reforms.

“It’s been a long, hard slog to get to where we are,” said Collins, “but now some people are saying this compromise stuff gets us nowhere and we should be doing things like enacting retroactivity for sentencing reforms, eliminating all mandatory minimums for drug offenses, and decriminalizing all drugs. Maybe it’s time to go maximalist.”

“My job is to continue to beat the drum for change,” said Gotsch. “It’s always hard, and we don’t get those opportunities a lot. Momentum doesn’t come very often, regardless of who is in power, and we can’t let these small windows close without doing our best to move the ball forward. This has been my concern for 20 years—the conditions these prisoners face, the injustice—and we will keep pushing. The federal prison system is in crisis.”

The federal prison population peaked at 219,000 in 2013, driven largely by drug war prosecutions, and has since declined slightly to about 181,000. But that number is still three times the number of federal prisoners behind bars when the war on drugs ratcheted up under Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. There is still lots of work to be done, but perhaps next time, we demand deeper changes.

This article was produced by Drug Reporter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.

The Drug Policy Alliance is a financial supporter of Drug Reporter.