By Tony Perry, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

If the trend holds, there soon will be a shelf of books explaining why the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan was a misadventure or worse.

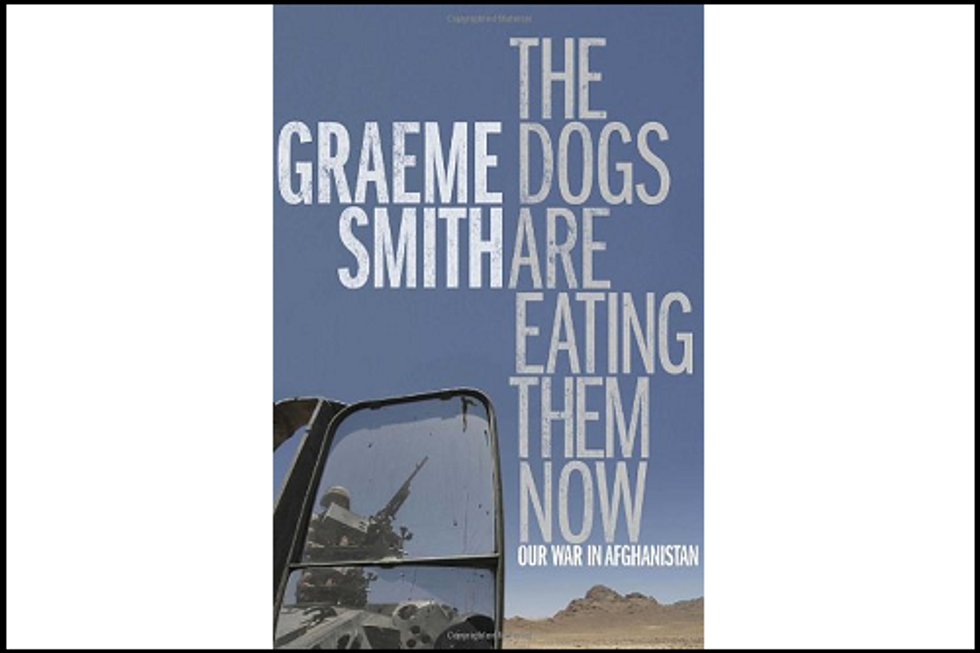

Into that crowded field comes Graeme Smith’s The Dogs are Eating Them Now: Our War in Afghanistan. But even among tomes of pessimism and clear-eyed hindsight, Smith’s book seems destined to be a standout: a compelling, self-revealing account of a reporter coming to grips with a big story and his own feelings of shock and disappointment.

Smith, a Canadian, is an anomaly among war reporters. His primary focus is neither the Western troops in the field nor the politicians in Kabul and Washington. Between 2005 and 2011, he did 17 stints in Kandahar in the southern region, long a Taliban stronghold. His goal was to get to know the region and its people, from poppy farmers to assorted crooks and killers.

How many other reporters, on a trip home, go shopping to buy a present for a warlord?

“I wandered for hours, wondering what I could give a guy who already has his own personal army.” Answer: a wristwatch.

Smith arrived in Kandahar full of optimism and a sense of the “nobility” of the mission to oust the Taliban. He admits that at first being in a war zone provided a kind of coyote-howling fun.

“This was a place where a guy could … belch when he wanted, and in some ways behave more naturally than is usually allowed,” he writes. “My mouth tasted awful, and my combat pants grew crusted with rings of salt from days of accumulated sweat, but it felt like an adventure.”

In the beginning he followed Canadian troops for his newspaper, the Globe and Mail. On repeated trips back to Kandahar he began to explore, among other things, the condition of prisoners in Afghan jails where brutality was common and Western officers — often Canadian — looked away and pretended not to know what was happening.

“Over and over, in separate conversations, the men [former prisoners] described how the international troops tied their hands with plastic straps, covered their eyes and handed them over to [Afghan] torturers. They described beatings, whippings, starvation, choking and electrocution.”

Smith wrote about torture for his newspaper, careful to report only those cases that could be documented: “One prisoner, for instance, said he was shoved into a wooden box and tormented with boiling water; I didn’t publish that anecdote in the newspaper because I couldn’t cross reference it.”

Western officials were insisting that the mission of bringing stability to Kandahar was succeeding. Smith found the opposite: Taliban assassination squads “behaved with terrible efficiency and usually without attracting much notice. We never heard of any arrests.”

Smith’s tone is unflinching; a reporter who has spent considerable time and effort on the story, he has the on-the-ground facts and sees no need to lard it up with advocacy or suppositions. He spent time with Afghan provincial officials, finding some honest, some not, and quite a few somewhere in the middle.

“Dogs” is not primarily a look at military tactics, but it touches on what, in hindsight, may loom large in any explanation of why the mission to win the support of Afghan civilians failed: tension between U.S. forces and their NATO allies.

Tension between coalition partners is not new — even in World War II there was Patton versus Montgomery, Eisenhower versus De Gaulle, etc. But Smith suggests that in fighting an insurgency, different methods used by coalition troops worked at cross-purposes, with some troops kicking in doors at night, others taking tea with tribal leaders during the day.

“All too often, the Europeans viewed the Americans as trigger-happy cowboys, while the U.S. soldiers saw their counterparts as weak and useless,” he notes. “Being hated by the Americans somehow made me loved by the British. The world’s greatest military alliance was clearly dysfunctional.”

Although Smith treads lightly on providing strategy advice, he also avoids the tendency to tally up heroes, villains and victims and call it a day. He currently lives in Kabul, a senior analyst for the International Crisis Group think tank. He has at least limited confidence that the Afghan security forces, bolstered by “a healthy budget from foreign donors,” may succeed in keeping the Taliban at bay:

“Perhaps the war will be finished for many U.S. troops,” he writes, “but the fight is far from settled. Afghanistan was an unsuccessful laboratory for ideas about how to fix a ruined country.”