By Becky Bach, San Jose Mercury News

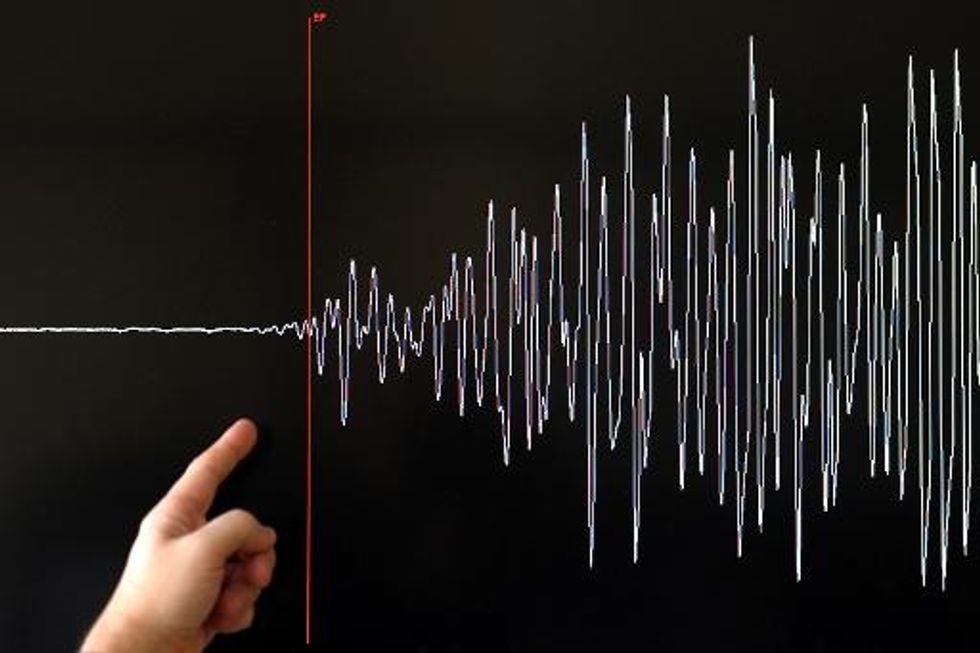

SAN JOSE, Calif. — The Bay Area’s Big One will still be plenty big, but it might not be just one, according to a study released Monday by U.S. Geological Survey scientists.

A flurry of midsized quakes is more likely to strike the San Francsico Bay Area rather than a giant 1906-esque rupture, said David Schwartz, a paleoseismologist at the USGS’s Menlo Park office and the lead author of the study, which appeared in June’s Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. The study marks the first comprehensive history of the Bay Area’s seismicity dating to 1600.

A quake cluster isn’t necessarily good news, as it could keep communities constantly cleaning up the earthquake damage, several experts said.

“It presents a very different problem in how you respond and recover from earthquakes,” Schwartz said.

After the 7.8-magnitude 1906 earthquake, the 20th century was abnormally stable, he said. Therefore, an earthquake cluster is overdue, the scientists said.

“Basically, what goes in, must go out,” Schwartz said. The region’s seismicity stems from the clash of two massive plates in the earth’s crust. The Pacific Plate is sliding northwest, while the North American Plate is moving southeast.

Since 1906, the plates have moved about 13 feet in the Bay Area. Like a compressed spring, they’re ready to burst.

In the Bay Area, the plate boundary fractures into a handful of fissures, all generally trending northwest-to-southeast. The well-known San Andreas Fault, which Schwartz calls the “master fault,” is accompanied by the San Gregorio Fault, the Hayward Fault, the Calaveras Fault and the Rodgers Creek Fault in the North Bay, among others.

Future quakes are expected to spread out along these faults.

“These faults are being stressed by the plate movements … and they all have to catch up,” Schwartz said.

The various faults “talk” to each other, said Roland Burgmann, an earth scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. “The communicating family of faults sometimes tend to rupture together as a group or shut each other off.”

The 1906 earthquake was likely a fluke, the perfect alignment of conditions that allowed 300 miles of the San Andreas Fault — from northern Mendocino County to San Juan Bautista — to release its pent-up pressure. This massive shaking kept the area unusually calm for a century, Schwartz said.

“Eventually, there should be more clusters,” Burgmann said.

The scientists based their prediction on the historical record, which shows a cluster of quakes shook the Bay Area from 1690 to 1776. At least six earthquakes, ranging from 6.3 to 7.7 magnitude, rattled the region’s major faults during that period, Schwartz said.

The cumulative release of energy from the quakes roughly equals that of the 1906 earthquake, Schwartz said.

“This is a summary of a tremendous amount of work,” said Greg Beroza, a Stanford seismologist who was not involved with the study.

Previously, other scientists had scoured the records kept by the Franciscan missionaries at San Francisco’s Mission Dolores starting in 1776, Schwartz said. He called the Spanish missionaries “the first seismographers.” They described the rumblings in their records, allowing scientists to assess the earthquake’s strength by extrapolating from the amount of damage the Franciscans described.

Scientists dated the earlier quakes by digging trenches and calculating the age of charcoal or other organic materials found several feet below the surface, Schwartz said.

This technique misses small or deep earthquakes, which don’t break the surface.

Although the scientists predict a group of tremors, rather than just a single, large earthquake, they admit the future could surprise them. The Bay Area has a 63 percent chance of one of more large earthquakes before 2036, according to estimates released in 2008 by the Working Group on California Earthquake Probabilities, a coalition of state, federal and academic geologists.

The USGS study provides a useful framework to plan for the future, said Thorne Lay, an earth scientist at UC Santa Cruz, who was not involved in the study.

Schwartz said he hopes to look back even farther than 1600 to more fully understand the Bay Area’s seismic history — and its future.

“The key question is when are we going to come out of the shadow, when are we going to go back to normal?” Burgmann asked.

AFP Photo/Frederick Florin