Reprinted with permission from ProPublica.

This article is a collaboration with The New York Times.

More than 700 people have left the Environmental Protection Agency since President Donald Trump took office, a wave of departures that puts the administration nearly a quarter of the way toward its goal of shrinking the agency to levels last seen during the Reagan administration.

Of the employees who have quit, retired or taken a buyout package since the beginning of the year, more than 200 are scientists. An additional 96 are environmental protection specialists, a broad category that includes scientists as well as others experienced in investigating and analyzing pollution levels. Nine department directors have departed the agency as well as dozens of attorneys and program managers. Most of the employees who have left are not being replaced.

The departures reflect poor morale and a sense of grievance at the agency, which has been criticized by Trump and top Republicans in Congress as bloated and guilty of regulatory overreach. That unease is likely to deepen following revelations that Republican campaign operatives were using the Freedom of Information Act to request copies of emails from EPA officials suspected of opposing Trump and his agenda.

The cuts deepen a downward trend at the agency that began under the Obama administration in response to Republican-led budget constraints that left the agency with about 15,000 employees at the end of his term. The reductions have accelerated under Trump, who campaigned on a promise to dramatically scale back the EPA, leaving only what he called “little tidbits” in place. Current and former employees say unlike during the Obama years, the agency has no plans to replace workers, and they expect deeper cuts to come.

“The reason EPA went down to 15,000 employees under Obama is because of pressure from Republicans. This is the effort of the Republicans under the Obama administration on steroids,” said John O’Grady, president of American Federation of Government Employees Council 238, a union representing EPA employees.

ProPublica and The New York Times analyzed the comings and goings from the EPA through the end of September, the latest data that has been compiled, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. The figures and interviews with current and former EPA officials show the administration is well on its way to achieving its goal of cutting 3,200 positions from the EPA, about 20 percent of the agency’s work force.

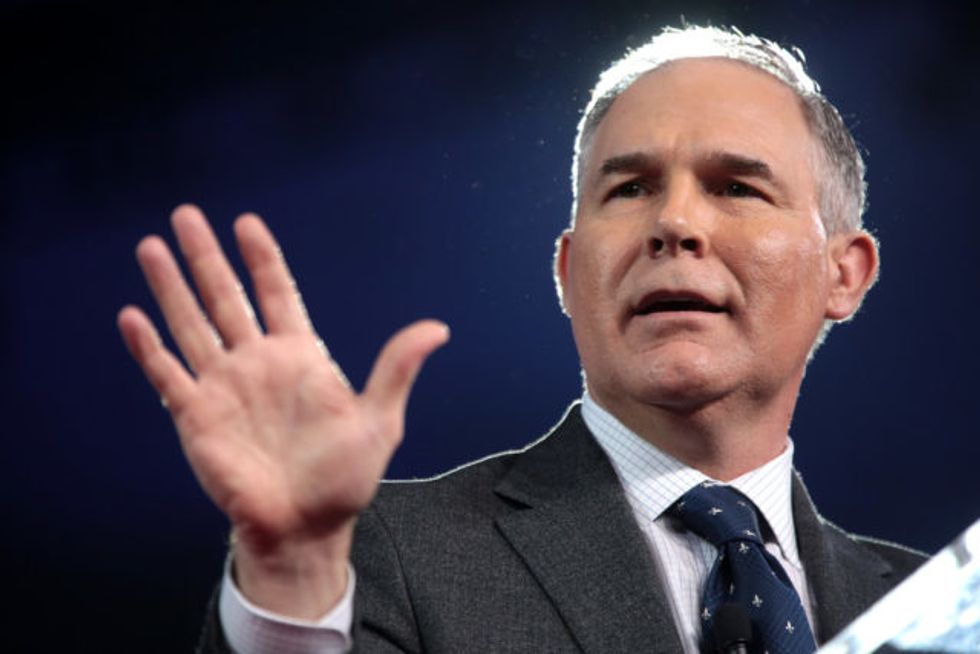

Jahan Wilcox, a spokesman for the EPA, said the agency was running more efficiently. “With only 10 months on the job, Administrator Pruitt is unequivocally doing more with less to hold polluters accountable and to protect our environment,” he said.

Within the agency, science in particular is taking a hard hit. More than 27 percent of those who left this year were scientists, including 34 biologists and microbiologists; 19 chemists; 81 environmental engineers and environmental scientists; and more than a dozen toxicologists, life scientists and geologists. Employees say the exodus has left the agency depleted of decades of knowledge about protecting the nation’s air and water. Many also said they saw the departures as part of a more worrisome trend of muting government scientists, cutting research budgets and making it more difficult for academic scientists to serve on advisory boards.

“Research has been on a starvation budget for years,” said Robert Kavlock, who served as acting assistant administrator for the Office of Research and Development before retiring in November. Under earlier buyouts, Kavlock said, the agency later hired nearly 100 postdoctoral candidates to help continue critical agency work.

“There wasn’t a reinvestment this time around,” he said. “There’s a hard freeze.”

Scientists, for the most part, are also not being replaced. Of the 129 people hired this year at the EPA, just seven are scientists. Another 15 are student trainee scientists. Political appointees, however, are on the rise. The office of Scott Pruitt, the agency administrator, is the only unit that saw more hires than departures this year.

In addition to losing scientists themselves, the offices at the EPA that deal most directly with science were drained of other workers this year. The Office of Research and Development — which has three national laboratories and four national centers with expertise on science and technology issues — lost 69 people, while hiring three. At the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, responsible for regulating toxic chemicals and pesticides, 54 people left and seven were hired. And in the office that ensures safe drinking water, one person was hired, while 26 departed.

By contrast, Pruitt’s office hired 73 people to replace the 53 who left.

“I think it’s important to focus on what the agency is all about, and what it means to lose expertise, particularly on the science and public health side,” said Thomas Burke, who served as the agency’s science adviser under Obama. “The mission of the agency is the protection of public health. Clearly there’s been a departure in the mission.”

Wilcox disputed that assessment and said the agency remained an attractive workplace for scientists. “People from across EPA were eligible to retire early with full benefits,” he said in an emailed statement. “We currently have over 1,600 scientists at EPA and less than 200 chose to retire with full benefits.”

The impact of losing so many scientists may not be felt for months or years. But science permeates every part of the agency’s work, from assessing the health risks of chemical explosions like the one in Houston during Hurricane Harvey to determining when groundwater is safe to drink after a spill. Several employees said they feared the departures with few replacements in sight would put critical duties like responding to disasters and testing water for toxic chemicals in jeopardy.

As of Dec. 6, there were 14,188 full-time employees at the EPA By comparison, there were 17,558 workers at the end of the first year of the George W. Bush administration and 17,049 by the end of the first year of President Obama’s term. The EPA offered two major buyouts during the Obama administration, losing 900 employees in 2013 and an additional 465 the following year. Hundreds of other workers left through attrition and were not replaced.

Pruitt’s office has described the current buyout process as a continuation of Obama administration efforts to ensure that payroll expenses do not overtake funding for environmental programs.

Agency staff said they believed the Trump administration was purposely draining the EPA of expertise and morale.

Ronnie Levin spent 37 years at the EPA researching policies to address lead exposure from paint, gasoline and drinking water, most recently working as a lead inspector at the agency’s regional office overseeing New England. She retired in November after what she described as months of low morale at the agency. And with the lead enforcement office targeted for elimination as part of Trump’s proposed budget, she said, “It was hard to get your enthusiasm up” for the job.

“This is exactly what they wanted, which is my biggest misgiving about leaving,” Levin said. “They want the people there to be more docile and nervous and less invested in the agency.”

Lynda Deschambault, a chemist and physical scientist who left the EPA at the end of August after 26 years, said her office in Region 9, based in San Francisco, had been hollowed out. The office saw 21 departures this year and no hires. “The office was a morgue,” she said.

Conservatives who helped lead the Trump administration’s transition and prepared for eliminating vast parts of the agency said scientists’ worries were misplaced.

“To me it’s not necessarily a sign of catastrophe,” said David Kreutzer, a senior researcher at the Heritage Foundation who advised Trump on the EPA during the transition. He said the agency under President Obama was engaged in “phenomenal overreach” and that the Trump administration’s efforts were aimed at correcting that.

In proposing this year to slash the EPA’s budget by 31 percent, Mick Mulvaney, director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, called the effort part of Trump’s plan to eliminate entrenched government workers. “You can’t drain the swamp and leave all the people in it,” Mulvaney said. “So, I guess the first place that comes to mind will be the Environmental Protection Agency.”

Jan Nation, who works in EPA’s Region 3, based in Philadelphia, where 46 people either retired or took a buyout this year, lamented the administration’s approach to federal workers. “We are not the swamp. The swamp are all the people who don’t have a specific function to make our government work,” Nation said. “If you have a swamp to drain, I know people in the Army Corps of Engineers who can do it.”

Talia Buford and Lisa Song contributed reporting to this article.