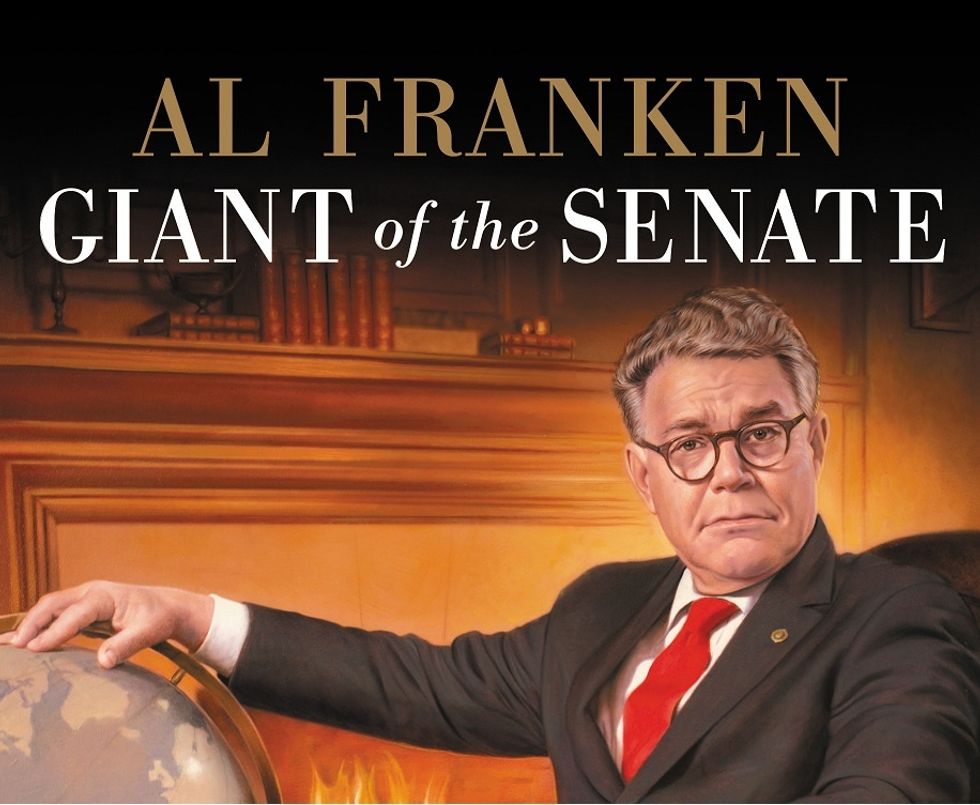

The following is an excerpt from Minnesota Senator Al Franken’s uplifting, uproarious, and absolutely serious new political memoir, Al Franken, Giant of the Senate, published by Twelve Books.

Two days before the 2016 election, Donald Trump landed his gaudy plane at the Minneapolis–St. Paul airport, making his first public appearance in our state just in time to spread his trademark blend of hate, fear, and ignorance—this time targeting our Somali-Minnesotan community.

Somalis started coming to America in large numbers during a civil war in the early 1990s. Many families had spent years in refugee camps in Kenya and elsewhere in Africa. About fifty thousand Somali refugees now live in Minnesota—many of them in the Twin Cities, but not all. Many smaller cities and communities around the state have significant Somali populations.

At the time, Trump was attacking Hillary Clinton’s plan to admit sixty-five thousand refugees out of the millions of people fleeing Syria in the worst refugee crisis since World War II. “Her plan,” Trump told the crowd, “will import generations of terrorism, extremism, and radicalism into your schools and throughout your community. You already have it.”

He wasn’t talking about Syrian refugees. So far, Minnesota has admitted twenty-eight of them. He was talking about the Somalis who have been here for years, people who are an important part of our state’s fabric.

“Here in Minnesota you have seen firsthand the problems caused with faulty refugee vetting, with large numbers of Somali refugees coming into your state,” Trump told the rally. He was referring to an incident two months earlier in which a young Somali man wielding a knife had injured nine people at a shopping mall in St. Cloud before being killed by an off-duty cop. The assailant had come to America when he was four months old. Which makes it kind of hard to buy that the incident was a result of “faulty vetting.”

The investigation is now in the hands of the feds, who have pos- session of the attacker’s electronic devices. By all accounts, the man had gone off the deep end. Not unlike the Iowa man with a Trump- Pence sign in his yard who had murdered two police officers ambush- style just four days before the airport rally. Of course, no one was accusing Trump of stoking the anger that led to the senseless police killings in Iowa. But here Trump was, blaming the Somali community for the knife attack in St. Cloud.

“You’ve suffered enough,” he snarled, talking about the presence of Somali people in our communities.

That’s kind of how Trump’s entire campaign went. His arguments were rarely rooted in fact, but they frequently carried a tinge of racism and paranoia. And that’s what made it so upsetting when he won. How could that be what America chose? Is that really who we are? And if so, what’s the point of trying?

The truth, however, is that, at least in Minnesota, that’s not who we are.

The day after the knife attack, St. Cloud’s police chief, William Blair Anderson, went on Fox and Friends, where perfectly named host Steve Doocy invited him to comment on Trump’s concerns “about who is coming to our country.”

Chief Anderson replied, “I can tell you the vast majority of all our citizens, no matter what ethnicity, are fine, hardworking people, and now is not the time to be divisive.” Shortly after the attack, I went to St. Cloud to meet with Anderson and St. Cloud’s fine mayor, David Kleis, a former Republican state legislator whom I’ve gotten to know well over the years. They assured me that the attack would not divide their cohesive community.

Look, a lot of Minnesotans voted for Donald Trump. And when I travel around Minnesota, I meet people who voted for him believing that only a true outsider could “drain the swamp” in Washington. I meet committed Republicans who were willing to hold their noses and vote for him so that the Supreme Court would stay in conservative hands. I meet people who bought into the misinformation spread about Hillary Clinton and couldn’t bring themselves to vote for some- one who was insufficiently attentive to proper email security protocols.

But where Donald Trump sees a state in which people suspect and resent their neighbors based on where they come from, I see a state where we look out for each other, because we believe that we’re all in this together. Trump might have found a clever way to channel the resentments of the white working class, and he sure does seem good at playing the media for fools, but he’s just plain wrong about what kind of people we are.

Willmar is an agricultural city of about twenty thousand in south- central Minnesota and the seat of Kandiyohi County, the largest turkey-producing county in the largest turkey-producing state in the nation. In June of last year, I took the unusual step of inviting myself to Willmar’s high school graduation. Not just for the free punch and cookies, but because I wanted to introduce the senior who had been voted by the graduating class to be their class speaker.

Her name was Muna Abdulahi, and she had been one of our Senate pages during her junior year. Her principal had recommended her to my office, and my staff told me that her essay and interview had been unbelievably impressive. So, the day the new class of pages arrived in the Senate, I went down to the floor to meet her in person.

Muna was easy to pick out of the group of thirty or so, being the only one wearing a hijab (headscarf) with her page uniform. I went up to her and said, “You look like a Minnesotan.”

Muna nodded and smiled. As we talked, I was struck by her poise and intelligence. A few weeks later, the ambassador from Somalia came to the Capitol to meet with a number of senators and members of Congress from states with large Somali communities. I invited Muna to come along so that the ambassador could meet her and see that a Somali Minnesotan was a Senate page.

The Class of 2016 at Willmar Senior High had 236 members. Perusing the list of graduates in the program, I estimated that about 60 percent were your garden-variety Scandinavian/German white Minnesotans, about 25 percent were Hispanic, and about 15 percent were Somali, with a few Asian Americans tossed in. The valedictorian, Maite Marin-Mera, had been born in Ecuador.

As the orchestra played “Pomp and Circumstance,” the graduates entered two by two, walking down the center aisle in their caps and gowns. Muna was up front, because “Abdulahi” was the first name alphabetically. She was holding hands with fellow senior Michelle Carlson, one of two Carlson twins to graduate that day.

The only way to tell Michelle and her twin sister, Mary, apart is that Mary has a slightly shorter haircut. Or maybe it’s Michelle. Otherwise, they’re identical—both are tall, both are brilliant (both graduated with highest honors), and both exude the same spirit of pure positivity and joy.

The whole day was like this. Maite gave a wonderful speech, and so did class president Tate Hovland (half Norwegian, half German), and both received enthusiastic ovations. I introduced Muna, who got a boisterous round of applause as she took the stage and a standing O when she finished.

When it came time to hand out diplomas, the crowd was told to hold their applause until the end. But they couldn’t help themselves. The moment Muna’s name was called, everyone erupted. Clapping, shouting, stomping on the bleachers—and it continued like that through each one of the 236 graduates. These kids loved each other.

The two hours I spent at that high school commencement were a tonic for the year of trash I’d been hearing about our country.

The previous year, I’d been in Willmar to help respond to an avian flu crisis that threatened the turkey industry that employs so many in Kandiyohi County. A number of producers were worried that they might lose their entire operations. But we were able to get some emergency funding to help keep them on their feet.

Were these turkey producers Democrats? Were they Republicans? No idea. Didn’t care. Don’t care. Will never care. Do they care that they have Somali refugees in their community? Yes, they do care. They want them. They need them. They need people like Muna’s dad, who works in IT at the Jennie-O Turkey store.

Perhaps Donald Trump confused Minnesota with somewhere else. About a week after the election, I spoke to Gérard Araud, the French ambassador to the United States. He told me that in France, a Frenchman is someone who can tell you what village his family is from going back centuries. Immigrants never really get to become Frenchmen. It made me think back to the hideous massacre in Paris the year before.

Here in America, of course, we’re all immigrants. Except, of course, for Native Americans against whom we committed genocide. I’m a Jew, but I’m also an American. Muna is Somali, but she’s also an American. On Election Day, I ran into her on campus at the University of Minnesota, where I was getting out the vote for Hillary. She told me that her sister, Anisa, had been voted homecoming queen.

That’s who we are. In places like France, they isolate their refugees and immigrants. In America, we elect them homecoming queen.

From the book Al Franken, Giant of the Senate. Copyright (c) 2017 by Al Franken. Reprinted by permission of Twelve/Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.