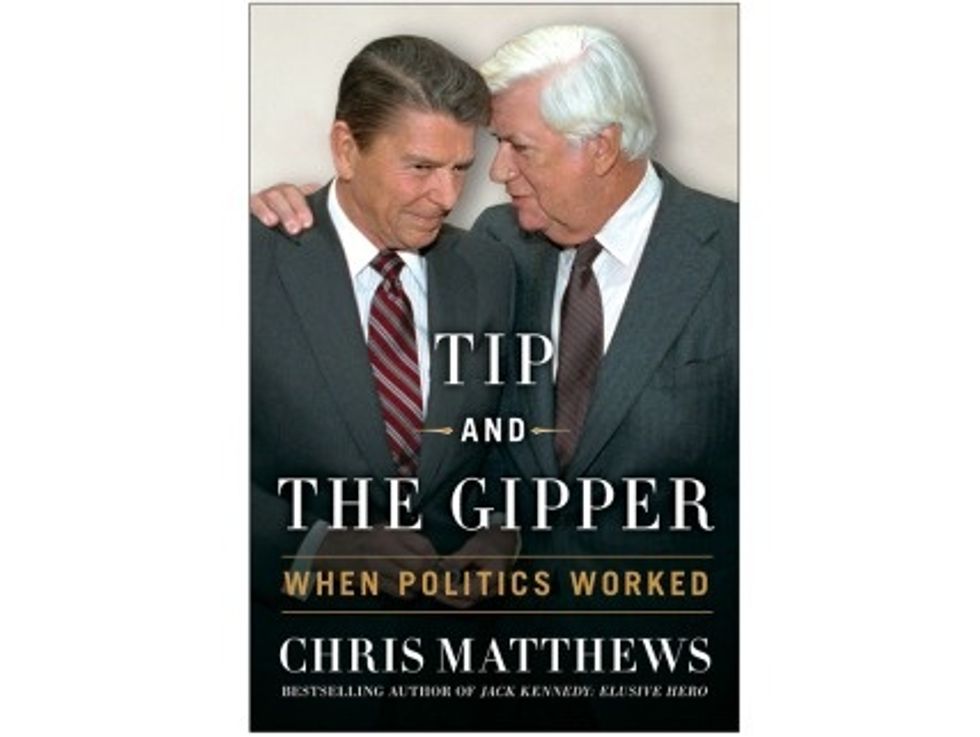

The National Memo brings you an excerpt from MSNBC host Chris Matthews’ recently released book Tip And The Gipper: When Politics Worked. In this excerpt, Matthews explores the unlikely relationship between House Speaker Tip O’Neill and President Reagan, and describes their ability to cross party lines and constructively work together — an important lesson for leaders in Congress today.

You can purchase the book here.

As a politician Tip O’Neill beautifully fit the classic mold. He’d come of age and learned the rules in a legislative world where his man-to-man skills paid off. In all the time-honored ways, he kept his constituents back home satisfied while gaining friendship and respect among his peers down in Washington. In both worlds, he’d learned how to take care of himself. He knew how to wheel and deal, trade favors, and use his anger when necessary. Most of all he understood the advantages of having a trick or two up his sleeve.

In the first month after Reagan’s inauguration, the president and Congress faced the nasty but predictable chore of having to raise the federal debt ceiling. It’s a ritual requiring members to put their names not to new government spending but to the settling of old accounts. In other words, it mandates that a majority of the national legislators behave the way individual citizens must: you agree to pay your bills. While every recent president has had to regularly sign off on a hike in the debt ceiling, it had become over the years a regular occasion for partisan blame-pointing. In the previous year, 1980, not a single GOP House member had cast a vote agreeing to a raise in the ceiling, a partisan tactic well understood by O’Neill. It left the Democrats solely responsible for the higher national debt, and gave Republican candidates free rein to finger their Democratic rivals as out-of-control Washington spenders.

Now the situation was different: a Republican was in the White House. But no matter the reigning ideology, the buck stopped where it always had. Therefore, just like his much-mocked predecessor, Jimmy Carter, it was now Ronald Reagan’s job to raise the debt ceiling. He couldn’t do it without the Democrats, the majority party in the House of Representatives. Bottom line: there was no way for the new administration to accomplish the job without asking the Speaker to help round up the needed votes.

When Reagan’s top lobbyist asked his support in getting the debt ceiling raised, the Massachusetts Democrat made a simple request. He wanted Max Friedersdorf to relay back to his boss precisely what the deal would be, which was that he, Tip O’Neill, wanted a personal note from the president to each and every Democratic member of the House asking for his or her support in the matter of raising the debt ceiling. Friedersdorf agreed on the spot and carried the message back to Reagan. The asked-for letters arrived the next day—all 243 of them.

It was a small, telling episode. Here was the Democratic congressional leader proposing a wholly pragmatic cease-fire. The debt-ceiling vote had offered each side a chance to discredit the other. O’Neill proposed avoiding harm to either party. Rather than have the House Democrats all vote “Nay,” as he might have allowed, throwing a monkey wrench into Reagan’s first-month agenda, the Speaker agreed to let as many as were necessary vote “Aye.”

The sole condition he’d made stemmed from his desire to help protect the sitting members from their opponents’ likely attacks come the next election. To accomplish this, he needed Ronald Reagan’s cooperation. Looking to the future, if a Republican challenger were to slam one of O’Neill’s Democrats for big spending, pointing to his vote to raise the debt ceiling as evidence, the note from Reagan would give him adequate cover. As an effective solution, it was an arrangement that worked, for both sides—and the republic moved on.

Dealing in such a way was Tip O’Neill’s style, but change was not, and those who knew him understood this. He’d come to the House of Representatives in 1953 with a predecessor, the rich and handsome young war vet, John F. Kennedy, clearly a hard act to follow. From his many dealings with JFK over the subsequent years, Tip knew charisma firsthand. Certainly, too, his great hero Franklin Roosevelt had possessed an overabundance. These experiences, however, had not prepared him for what he now faced.

Tip now saw the response Reagan drew on February 18 at his first joint session of Congress. It was like nothing he’d ever witnessed. As tough and proud as he was, Tip must have glimpsed the shape of his future as he looked out into the historic chamber at all those familiar faces, many of whom he’d worked alongside, or in opposition to, for decades. Watching Reagan’s effect on them, he could see both the appeal and, for him and his fellow Democrats, the menace.

When asked later about the seemingly mesmerized response to Reagan’s appearance that night, O’Neill was candid. With the professionalism that anchored his political self, he told the press that the public reaction to the president’s performance was “tremendously strong.” He didn’t stop there: “I don’t know how many telegrams we’ve received. . . . The honeymoon is still on, no question about it.”

As the weeks passed, O’Neill continued to feel the glare of Reagan’s star power even if he chose not to admit it. Asked in early March if the new president’s honeymoon was “wearing thin,” he didn’t take the bait. “We are not ready to play hardball yet,” he said. Yet it was clear that the seeming ease with which the administration was getting out its message—with neither press nor public ready to break the spell—bothered him. “What I am curious of is the honeymoon with the press. I don’t recall any president and a press having a honeymoon as this one.” Soon, by the time only another week had passed, he was starting to acknowledge the challenge being put to him. What he admitted, cautiously, was that the Democrats themselves, under his leadership, might bear some responsibility. “We haven’t communicated well with the press,” he said.

But still, it was a problem he understood how to address, at least on one level. The reporters covering the Hill were a known quantity. Faithfully, every day the Speaker would appear fifteen minutes before each House session in H210, his ceremonial office, and take their questions. He and they all understood the rules. There were no TV cameras present. For Tip, it was facing the world beyond H210 that threw him from his comfort zone.

“He was very persuasive with people individually or even in small groups but as a public speaker, it wasn’t his strength,” his daughter Susan told me. “And he knew that about himself, which is why he didn’t like going on camera initially.” Tip never minded admitting to his uneasy relationship with television; it was old news to him. “As you know,” he’d joked to a group of journalists the year before, “I haven’t won many campaigns based on my looks.”

The career he’d made for himself, starting in Massachusetts, had been constructed in the age before television. Like Reagan, he’d grown up listening to the radio. But, unlike Reagan, his career hadn’t begun in front of a microphone. Instead, he’d cut his teeth in person-to-person politics. Becoming over time a Capitol Hill insider, he’d ascended to the Speaker’s chair through the potent mix of backroom popularity and cajolery. That was the way you did it, and he’d proved himself an adept maneuverer. The skill sets of the U.S. Congress were ones he’d observed throughout his career, matching and bettering them as needed.

The problem was, a different game was now afoot, and new talents were about to be asked of him. He’d be going up against a master of a medium, television. A few of the people around Tip recognized the problem and were in the market for a solution. One thing was for certain: he couldn’t continue to hold back.

Early in 1981, I’d received a call from Martin Franks, whom I knew from the Democratic National Committee. He had an idea he wanted to discuss, one that would involve me. I was ready to listen. Back in the fall, I’d often counted on Marty to help with party back- ground info on campaign speeches I was writing for Jimmy Carter. Now he’d moved on to a bigger job—executive director of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC)—and was thinking about the task before him in large terms. The Democrats had lost the White House and the Senate; the House now was their last redoubt. As the majority party there, they needed to be heard from; they needed to make noise, make it frequently, and make it matter.

If you enjoyed this excerpt you can purchase the full book here.

From Tip And The Gipper by Chris Matthews. Copyright © 2013 by Christopher J. Matthews. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.