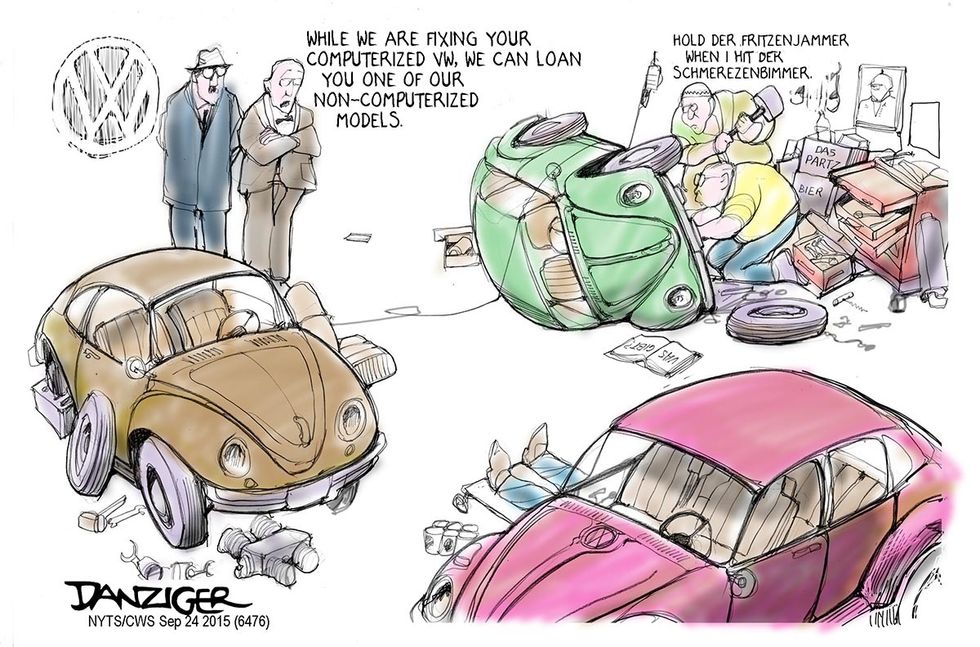

I have owned, back in my earlier life, seven Volkswagens, six of them Bugs. They promised traction, because the engine was in the rear. Through Vermont winters, they got a grip on the road to get up the hills by digging into the snow and mud, the twin curses of New England weather.

The Bugs, or Beetles, did pretty much what they were expected to do. They were cheap to buy, pretty cheap to fix, and cheap to run. They were also miserable by design. They were cold in winter, hot in summer, noisy at all speeds, and cramped for anyone over five feet tall. They could easily have been made warm in winter, because after all the engines were air-cooled. Porting some of the hot air, blown out into the atmosphere, up to the suffering passengers, would have been an engineering trick of a few minutes. VW didn’t do this.

So we were cold and miserable getting to work in the refreshing Vermont winter mornings. And unsafe because there was no defroster worth a damn. Supposedly some air had been directed at the windshield by running ducts up front from the engine through the rocker panels under the doors. Guess what? The defrosted air was well cooled by the time it reached the windshield, and therefore useless. And the rocker panels rotted quickly in the Vermont salt — another design plus.

The Volkswagen Beetle or Bug was a reminder that you were poor, that this was all you could afford, that you drove this minimalist machine while others cruised happily by in an American boat, maybe a Ford, with the heater blasting. Naturally, we VW victims turned the whole experience into a virtue, possibly the mental result of near-hypothermia. Or possibly carbon monoxide poisoning, another product of the heating system.

The rear engine design meant the gas tank had to be placed in front of the dashboard. In a head on collision everyone was covered with gasoline. This in some subtle way reminded us that Adolf Hitler was responsible for the initial development of the car. Early versions had no gas gauge. If you ran out of gas, there was a reserve tank that you opened with a small valve under the steering wheel. This released another gallon to get you to a gas station. A nice simple design, except that the valve often leaked on the driver’s shoes.

VW Bugs rusted at a rate unequaled even by the standards of American manufacturers. A design feature was that the parts, fenders, running boards, quarter panels (and so on) were easily replaceable if they got rusty. A few nuts and bolts, and you were good to go. This theory was a selling point, but failed in practice, since the entire car rusted at an even rate, even the places where you were supposed to bolt the replaceable parts on. But the engine made so much noise that you couldn’t hear the body rattles, until, of course, it was too late.

The engine was good for maybe 50,000 miles. It was an environmental nightmare, horribly inefficient, unevenly cooled so that one cylinder (I forget which one now) always burned out before the rest. The linkage to the clutch (no automatic transmission for you!) was sloppy and prone to rust. The other controls were in constant need of adjustment, tightening, oiling, and generally fiddling with. The brakes were the bare minimum, although the car was light enough that some stoppage was available by opening the door and dragging your foot.

VW did not make what would have been easily made changes to the design. They could have fixed the heater. They didn’t. They could have stopped the oil leaks. They didn’t. They could have countered the rust. They didn’t. The inhuman aspects of the VW Bug went uncorrected for years. The price remained low, but as in the case of Henry Ford’s stubborn refusal to improve the Model T, the low price was not a sufficient lure after you had three or four. (As I say, I had six Bugs, which may say something about my intelligence. My excuse is Vermont teachers’ pay.)

For a period after VW sold the design and the machinery to the government of Mexico (shades of the Zimmermann Telegram!), VW tried one disastrous improvement after another. They lost market share in the U.S. and Europe precipitously. They were saved, unremarkably, by the German government. Slowly, their designs improved and they elbowed their way back to success.

Volkswagen is now a colossal enterprise. Their new cars are pretty luxurious, and they’re clearly not people’s cars, certainly not the people I was back in the 70s. Companies change and customers change. Even so, I remember what VW was. The Bug was inhuman, noisy, cold in winter, hot in summer, stubborn in its refusal to improve, and unsafe. But the main difference between the clattery, rusty, underpowered, wheezing, cramped, and funny-looking Bugs I drove, and the Volkswagens of today is that the Bugs were honest. They didn’t promise anything they didn’t deliver. They didn’t try to fool you into thinking you were in a higher class than you were. You didn’t actually grow to love them, but you appreciated the steady urge they produced to graduate up to something better. And now, as we realize, that won’t be a Volkswagen.

After my last Bug I bought a Subaru. Mostly for the heater.

—

Jeff Danziger is a political cartoonist. He recommends E. B. White’s essay on the Model T, “Farewell, My Lovely”, viewable online at The New Yorker.