Reprinted with permission from Creators.

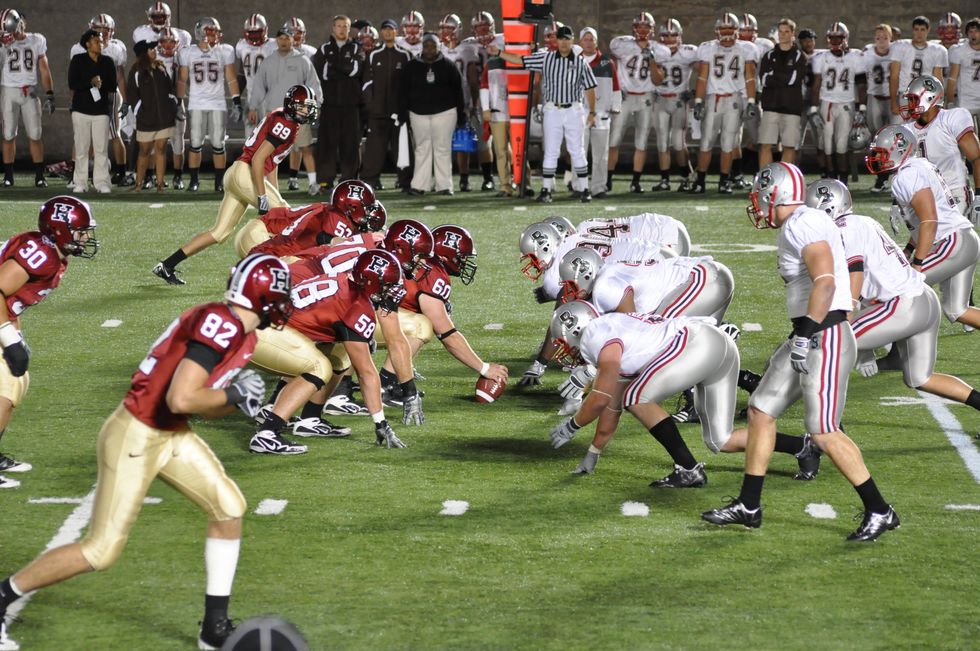

Harvard and Yale are among the premier educational institutions in the world. They have spent centuries at the task of strengthening and elevating young minds. But on Saturday, Nov. 18, they will join together in a ritual guaranteed to damage young brains: the Harvard-Yale football game.

The two universities have been meeting on the gridiron since 1875, in one of the oldest rivalries in college sports. The tradition even inspired an acclaimed documentary film about the 1968 game, “Harvard Beats Yale 29-29.”

Ivy League football is no longer a big deal on the intercollegiate sports scene, which is dominated by large public universities such as Ohio State and Alabama. But Harvard (my alma mater) and Yale continue to send out undergraduate students to represent them in varsity football, oblivious to growing evidence that it does grave and irreversible harm to mental functioning.

At this point, a heavy burden of proof lies on those defending the game. A study of the brains of 202 deceased football players by neurologists at Boston University found markers of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in 99 percent of NFL veterans and 91 percent of those who played only through college. CTE is an incurable terminal disease that, according to the Concussion Legacy Foundation, causes “memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, and eventually progressive dementia.”

Skeptics scoff that the brains are unrepresentative because they were donated by those who suspected something was wrong. But the number of documented victims is too large to be dismissed.

CTE “was previously considered quite rare,” noted BU neurology and pathology professor Ann McKee. “There’s just no way that would be possible if this disease were truly rare.” She found the data “very shocking.”

Football also causes concussions, transient but disabling brain traumas that are as much a part of the sport as homecoming. Yale economist Ray Fair documents that there are, on average, 4,740 concussions each year in college football.

Steven Flanagan, co-director of the Concussion Center at New York University Langone Health, told NPR that 10 to 20 percent of concussion victims “may go on to develop chronic problems,” including depression and anxiety, caused by brain atrophy.

How can these two institutions rationalize a pastime so antithetical to the well-being of undergraduates and their own educational missions? It’s the equivalent of the Mayo Clinic operating a tobacco shop on-site. While athletics may be a worthwhile part of a well-rounded life, any sport practically designed to impair mental functioning can’t be justified as a university endeavor.

At least I can’t think of any justification, and neither school is willing to provide one. I emailed their spokespeople several times. Yale’s director of external communications, Karen Peart, told me only, “As a league, we are closely studying all of the data and consulting with our medical teams.” Harvard’s associate athletic director, Tim Williamson, with whom I had previously corresponded, didn’t respond at all.

Silence may be the best option when your position is indefensible. It’s hard to find a good way to end a sentence that begins, “We continue to sponsor a pastime that wrecks students’ brains because…”

Not that the schools are entirely blind to the hazards. In 2016, the Ivy League banned live tackling in practice, and Harvard had gotten rid of it years before. The conference has also experimented with changes in kickoffs and touchbacks to improve safety.

But fiddling with the rules to reduce risk is like advising alcoholics to cut back. Short of giving up tackle football, these schools are ensuring that a significant number of students will suffer serious injuries to their excellent brains.

Harvard and Yale, of course, are just two of the hundreds of colleges that have varsity football teams. Why should they be singled out for doing what so many are doing?

One reason is that elite educational institutions have large responsibilities. Universities that are academic leaders have no business pretending there is no problem or waiting for others to act.

Their stature also gives them outsize influence. If Yale’s Peter Salovey and Harvard’s Drew Gilpin Faust were to move to abandon the sport for reasons of health and safety, administrators at other colleges would be confronted with the question in a way they could not avoid.

With every game, Yale and Harvard are knowingly exposing their young charges to the serious risk of permanent incapacitating neurological injuries. How many students’ brains have to be wrecked before they decide to stop?

Steve Chapman blogs at http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/chapman. Follow him on Twitter @SteveChapman13 or at https://www.facebook.com/stevechapman13. To find out more about Steve Chapman and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.