I Hate Sports, But Love Watching Trump Be Enraged By Black Millionaires Who Tell Him Where To Get Off

Reprinted with permission from AlterNet.

I do not like sports. There are lots of other things I hate more—cancer, genocide, lite jazz—but ultimately, they’re all separated by a matter of degrees. I don’t care who won last night’s game, who’s in anyone’s brackets or how great the Whatchamacallits are “looking this year.” But while the sporting aspect of sports may strike me as boring, for the past few years, I’ve been pretty taken by the on- and off-field political commentary coming from sports stars using their platforms to call out oppression and social injustice. This refusal to be apolitical is a sign of the times that speaks to both the historic importance of this cultural moment while simultaneously underscoring all the awful reasons why their voices are needed.

That, and there’s nothing like watching Donald Trump’s rage at having black millionaires tell him where to get off.

You can basically sum up this country’s political spectacle for the last two years as crazy, racist, old man Trump yelling at people of color to get off his lawn, a patch of land known as America. But no group stirs Trump’s—and his followers’—ire quite like rich black folks, whose success they believe is always unearned, more prima facie evidence of a system that now gives black folks a leg up over deserving, hard-working, real—and thus definitionally white—Americans. Rich black folks who dare criticize this country instead of endlessly thanking mythical, benevolent white America for successes their own talents and ambition actually garnered are the particular targets of Trumpian anger and racial resentment. In a recent Politico piece attempting to explain Trump voters’ unwavering support for their president, Michael Kruse concludes, “it’s evidently not what he’s doing so much as it is the people he’s fighting,” a list that includes “NFL players (boy oh boy do they hate kneeling NFL players) whom they see as ungrateful, disrespectful millionaires.”

That’s fitting for a political movement without a single unifying element except its rejection of eight years of leadership by an African American so uppity he thought his rightful place was in the White House. “For Trump,” Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote in a recent Atlantic piece, “it almost seems that the fact of Obama, the fact of a black president, insulted him personally.” Trump and his supporters appear to feel just as insulted by the reality of millionaire black sports stars. It’s true that Trump’s belligerence is boundless, his outsized insecurity fueling his counter-attacks against even the mildest of perceived slights. But Trump goes after powerful black folks with a particular vengeance that is both politically expedient—his base absolutely eats these displays up—and attributable to his own deep-seated racism.

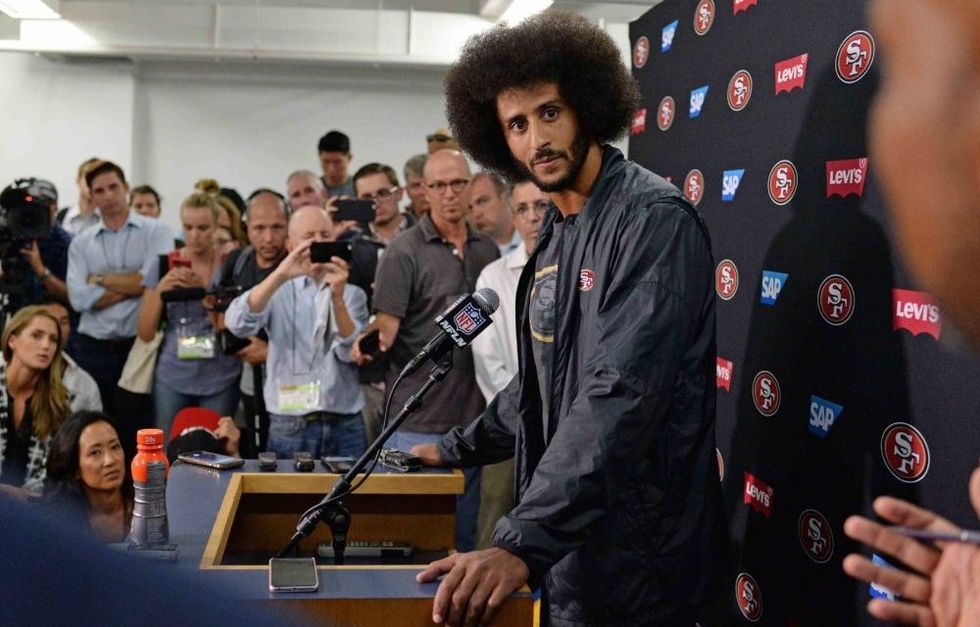

More than a year ago, Trump suggested that Colin Kaepernick “should find a country that works better for him.” The San Francisco 49ers quarterback had already begun sitting, and then out of respect for veterans, kneeling, because he asserted, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color.” Since then, Trump has used the office of the presidency to demand an apology from a private citizen, ESPN sports reporter Jamele Hill, who rightly declared via her personal Twitter account that “Trump is a white supremacist who has largely surrounded himself w/ other white supremacists.” Trump embarrassed himself by angrily attepting to disinvite Warriors point guard Steph Curry from the White House a day after Curry had already said he would turn down any such invitation to show he doesn’t “stand for basically what our president…the things that [he’s] said.” Trump tweeted that NFL players, 70 percent of whom are black, have been given the “privilege of making millions of dollars in the NFL,” as if talent, hard work, and years of rigorous physical training have nothing to do with it. A day earlier, Trump called peacefully protesting NFL players “sons of bitches”—a stark contrast to his “very fine” white nationalist and neo-Nazi supporters in Charlottesville—and demanded their firing, a direct assault on their First Amendment rights. (In that same speech, Trump bemoaned NFL rules designed to protect against traumatic brain injury claiming players “want to hit”; just the language a white racist would use to animalize black minds and bodies he imagines exist solely to be brutalized for his own entertainment.)

But for all Trump’s efforts to silence black sports figures—even those quasi-stars on the periphery, which I’m just about to get to—he’s failed miserably. There may be no better case than the recent back and forth between Trump and LaVar Ball. Trump petulantly demanded, and received, a thank-you for his alleged part in obtaining the release of Ball’s son LiAngelo, one of a trio of black UCLA players accused of shoplifting in China. When the elder Ball refused to praise Trump and downplayed his role in facilitating the release, the petty president sent a series of tweets insisting “IT WAS ME” who deserved both credit and profuse thanks, claiming Ball “could have spent the next 5 to 10 years during Thanksgiving with [his] son in China,” and calling him an “ungrateful fool” and a “poor man’s version of Don King, but without the hair.” (In the midst of this pre-dawn tirade, Trump inexplicably wedged in a complaint about Oakland Raiders running back Marshawn Lynch, figuring while he was attacking “the blacks” in sports, he might as well throw another one on the pile.) In the CNN interview that preceded Trump’s outburst, Ball dismissively stated, “I would have said thank you if he put [LiAngelo] on his plane and took him home. Then I would have said, ‘Thank you, Mr. Trump, for taking my boys out of China and bringing them back to the U.S.’ There’s a lot of room on that plane. I would have said thank-you kindly for that.”

I’d never thought much either way about the senior Ball before. He’s famous enough that he’d appeared in my non-sports-oriented news feed, mostly with the dubious distinction of being a class A sports dad. His recent resistance to standing down for Trump has basically made me a fan by default. It’s true that in Ball, Trump met his match, the only other public figure with a mouth as big and an ego as undeservedly huge. But Ball’s refusal to comply with Trump’s belief that black celebrities must acquiesce to his every demand comes off as a political act. It’s not a coincidence that black players who refuse to stop acknowledging the reality of systemic racism are consistenty accused of being unappreciative. As Shaun King noted in a recent tweet, “Ungrateful is the new nigger.” Trump’s consistent record of playing the race card—which is how that phrase should properly be applied going forward—managed to do what I’d never previously thought possible. As long I don’t have to actually participate in any organized sports, I’m fully Team Ball.

Ditto my support for LeBron James, who on the heels of Trump’s miserable failure to diss Steph Curry, blasted Trump as a “bum” and noted that “going to White House was a great honor until you showed up!” In a video followup, James stated he was “a little frustrated because this guy that we’ve put in charge has tried to divide us once again,” adding that for Trump to “use [sports] to divide us even more is not something I can stand for and it’s not something I can be quiet about.” Jamele Hill, after a two-week suspension from ESPN that Trump likely hailed a victory that would shut her up, pointedly stated in an interview that she “will never take back what [she] said.” Colin Kaepernick, proving this was never about Trump—who’s just the most obvious symptom of America’s problems—has kept on being awesome, charitable and outspoken on all the right issues despite an obvious conspiracy to keep him off the field. Steph Curry called Trump’s response to his non-RSVP “surreal” but also intimated that Trump was stoking racial flames, an issue we should never stop talking about.

“I don’t know why he feels the need to target certain individuals rather than others,” Curry told reporters following a Warriors practice. “I have an idea of why, but it’s kind of beneath the leader of a country to go that route. It’s not what leaders do.”

That’s also true. Trump has been deafeningly silent in response to white sports figures who have criticized him, from Warriors coach Steve Kerr (who has called Trump a “blowhard” who “couldn’t be more ill-suited to be president”) to San Antonio Spurs coach Gregg Popovich (who dubbed the president a “soulless coward”), to a number of NFL, NBA and MLB owners who have criticized Trump and defended protesting players. Trump even ignored Eminem’s BET cypher in which he labeled the president a “racist grandpa,” among many other insults. “I feel like he’s not paying attention to me,” the rapper said Friday, and I’m sure we can all guess why.

Friday, Trump lamented that NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell “has lost control” of a league in which “players are the boss,” which is to say the help have forgotten their place. That was the day after Thanksgiving, when he enthusiastically replied “Make America Great Again” in response to a tweet criticizing his racist attacks on “high-profile” black folks. (Some have theorized it was a technical “mistake,” which is not how you spell “Freudian slip.”) Trump will keep tossing red meat to the white supremacists who comprise the bulk of his base, and he doesn’t mind sharing the meal. And those sports stars who have spoken up will hopefully keep telling him exactly where he can stick it. I’m not hailing this as a revolutionary act, or pretending those words are going to radically transform white racists into decent people. But every time Trump is reminded it’s 2017 and uppity black folks are still talking, there’s a tiny bit of joy to behold.

Kali Holloway is a senior writer and the associate editor of media and culture at AlterNet.