ROCK HILL, S.C. — Why was South Bend, Indiana, mayor and Democratic presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg in South Carolina over the weekend, with a busy schedule that included tailgating at a historically black college homecoming and delivering remarks at an AME Zion worship service?

“To say that I want to be the president who can pick up the pieces, that we’ve got to be ready not just to defeat this president but to guide the country forward,” he confidently told me. “I have my eyes on that moment and what America’s going to need.”

It’s quite a tall order for a candidate polls show in single digits in the first-in-the-South primary, where he is still largely unknown to the African Americans who make up the majority of the state’s Democratic voters, even as his campaign coffers and Iowa poll numbers rise. In a weekend packed with public appearances, he and a diverse group of campaign workers and surrogates, including some from South Bend, were trying to catch up — and distribute those “African Americans for Pete” buttons.

After a pep talk to a not so racially diverse group of volunteers who gathered in a black-owned meeting space in downtown Rock Hill before spreading out to canvass on Sunday afternoon — “Let’s have some fun,” he told them — we spoke in the (closed for the day) beauty parlor and spa in the back. It will be more hard work than merriment for Buttigieg and his supporters in South Carolina, where former Vice President Joe Biden still holds the lead and a lot of loyalty with African American voters.

What would canvasser Buttigieg say to those voters who answered the door? He said he would “share the story of my experience as somebody whose life has been shaped by politics in ways both good and bad. There was a decision in Washington that sent me to war; there was a decision in Washington that made my marriage possible. At so many moments, my life and my community’s life has been shaped by all the things that they talk about on Capitol Hill.” He would “make sure they understand that that’s what propels me and what makes me tick.”

“We can’t go on like this or we won’t recognize our country.”

Enthusiasm was high among those who are already committed.

“I love that he’s kind and compassionate and patriotic,” said Janie Westenfelder, 56, who manages a women’s clothing store in Charleston, and had traveled to Rock Hill to volunteer. She has been a supporter, she said, since she read Buttigieg’s “Shortest Way Home,” copies of which were a common sight in the room, and heard him at the South Carolina Democratic Convention in June. While not many mayors could make the leap to the White House, she said, Buttigieg is “smart enough to get the right people in the room.”

Other voters will need more convincing.

For Buttigieg, the weekend, which included a criminal justice forum, provided an opportunity to tout his Douglass plan — “a comprehensive investment in Black America,” the info card said — to address everything from health policy and education to voting rights and the racial wealth gap; and his comprehensive criminal justice reform program, which includes not only assistance for those in prison, during and after incarceration, but also training for law enforcement on issues specific to marginalized communities such as restrictions on use of force by officers.

Why should black voters believe he would be able to implement his plans nationally when tensions between police and minority citizens in South Bend, which escalated after a police shooting, remain, and Buttigieg himself, when asked at a debate why the proportion of black officers dropped during his tenure, said, “Because I couldn’t get it done.” It was not just my question but one I’ve heard from quite a few black voters, and not just in South Carolina.

“We’re not out saying that it’s ever been perfect, and South Bend’s journey has been a complex one,” he said, “but we’ve also taken a lot of these kinds of steps in South Bend making sure that we’re supporting people in low-income neighborhoods that were under-invested.” He said the city is involving the entire community in accountability on policing. “It’s part of what motivates what we seek to do nationally with the Department of Justice.”

“But if we don’t have the presidency, if we don’t have the federal government aligned around these issues, if we’re not insisting that the White House be a force for equity, then I don’t think we’re ever going to get there.”

South Bend experience

Two African-American women spotlighted their own South Bend experiences. Arielle Brandy, 29, the campaign’s Indiana state director, spoke to me about the mayor’s leadership on creating generational wealth and strong leaders in the community. When she became involved in Indiana politics, she said, “Anytime I needed resources, he was always my first contact.”

It was the first time as a campaign surrogate for Janet Evelyn, a consultant, project manager and coach. She said she first met Buttigieg after she moved to South Bend several years ago as campus president of the local community college. Though Evelyn had to wait for a face-to-face until Buttigieg returned from active duty, when they met, she said he asked, “How are they treating you in South Bend?” Two weeks later she was in the mayor’s office. She said he brought monthly meetings of his staff to the college and spoke with students and parents. Evelyn, who served on the city’s diversity task force and the My Brother’s Keeper board, said the mayor is “genuine, humble and knows the issues,” adding that she would urge black voters, “Please, just listen to his message.”

That may be complicated because of information leaked — not from his campaign, it says — that black voters, particularly if they are older, socially conservative and Southern, may not be as welcoming to a gay candidate. In the ensuing reaction and backlash, some black voters with many questions about Buttigieg’s experience and candidacy wondered if incomplete information from a very small focus group would be used to blame low poll numbers on the perceived prejudices of an entire group, and build a divisive narrative.

“I think honestly anyone who’s been — and I’m not trying to say there’s an equivalency here because everybody’s experience is different — but I think anybody’s who’s been on the wrong end of a pattern of exclusion can find a lot of solidarity right now,” Buttigieg said.

“And so even though some of the traditional political advice would say not to do this, it’s actually part of my outreach, too, making sure black voters know where I come from and my story. Not because my experience lets me know exactly what it is like to be black in America, but because I know what it’s like to have my rights come up for debate, and I know what it’s like to wonder if I will be denied opportunities because of who I am, and because I know that I have rights that came not only because of the activism of people like me but because of the alliance of people not like me.”

In South Carolina, where voters of all races take their politics and early-primary status seriously, people are listening, even if they have not quite made up their minds. On Sunday, that included building owner Antonio Barnes, who advised Buttigieg to “show his face” and “be present.”

Retired librarian Mary Sanders, 63, has seen changes in her Rock Hill and fears the folks she half-jokingly called “relics” are being forgotten amid gentrification. Her concerns include health care costs and opportunities for those on a fixed income.

So far, Sanders, who is African American, said she has attended events featuring Biden and Sens. Kamala Harris and Cory Booker. She sat right up front to hear what Buttigieg had to say, to be “aware of what’s going on in the community.”

“I’m just looking around,” she said, and smiled.

Mary C. Curtis has worked at The New York Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Charlotte Observer, as national correspondent for Politics Daily, and is a senior facilitator with The OpEd Project. Follow her on Twitter @mcurtisnc3.

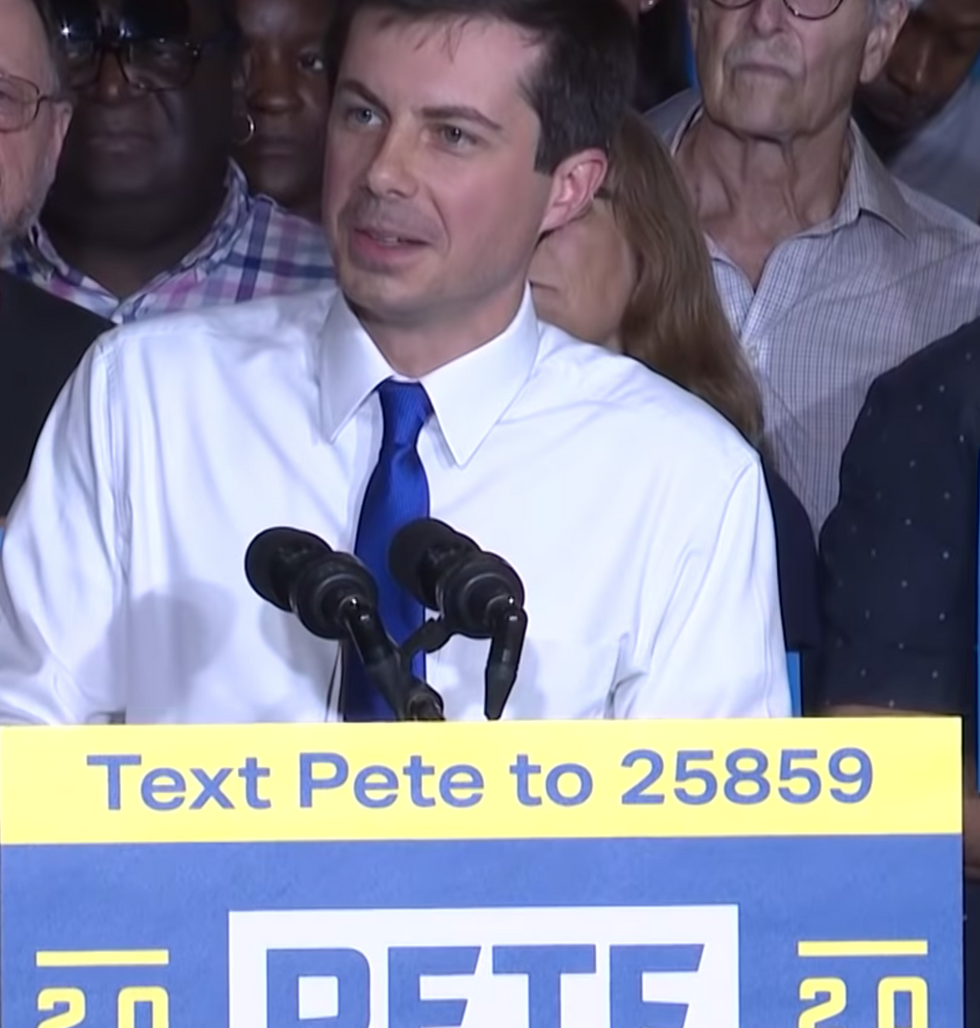

IMAGE: Pete Buttigieg, mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and Democratic presidential candidate in Charleston, South Carolina.