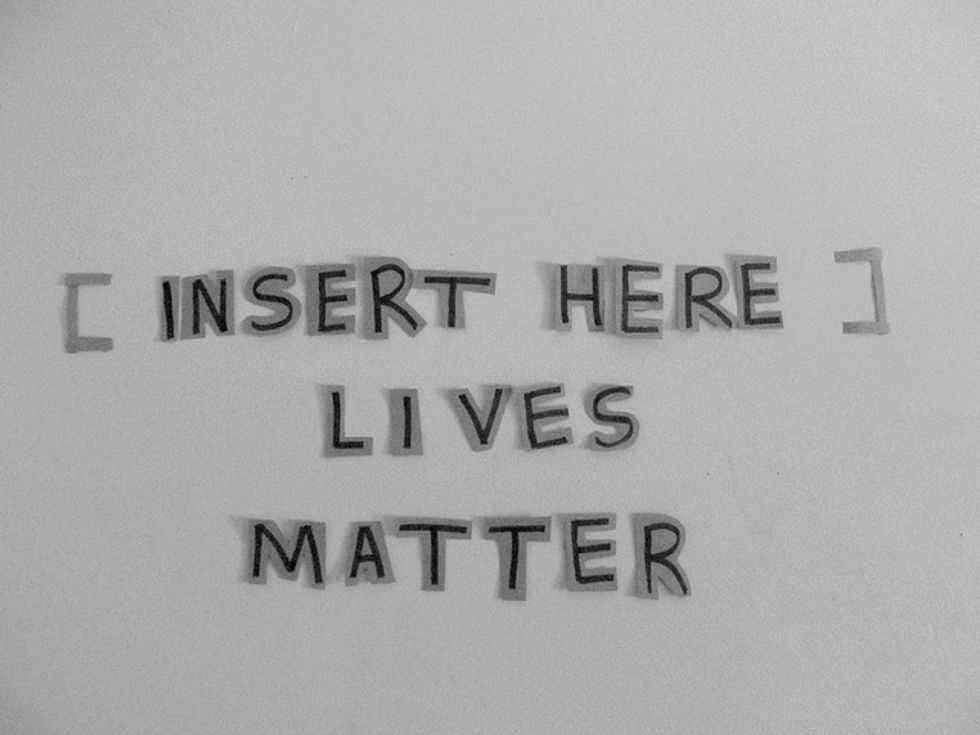

If ‘All Lives Matter’ Is Politically Toxic, Can Anyone Build A Coalition?

By David Lightman, McClatchy Washington Bureau (TNS)

WASHINGTON — Saying “all lives matter” has become a political liability in Democratic circles, which says a lot about how influential blocs are shaping the 2016 political debate.

When Hillary Clinton and Martin O’Malley uttered those words recently and triggered the wrath of black activists, the Democratic presidential candidates moved swiftly to make amends. Bernie Sanders also drew their ire, defended himself by noting his long-standing support for civil rights and was ridiculed. He’s since taken steps to show he, too, cares.

“The idea of saying everything matters undercuts the value and point of highlighting black life as something worthy of concern,” explained Katheryn Russell-Brown, director of the Center for the Study of Race and Race Relations at the University of Florida law school.

The rapid responses of the Democrats, all of whom have long liberal and civil rights resumes, may have crossed a risky political line where they look overly beholden to a powerful, demanding constituency.

Both political parties struggle with where to draw that line. Republicans fear alienating evangelical conservatives and tea party activists. Democrats worry about angering racial minorities, single young women and gay rights advocates.

The political danger is not that these constituencies will switch sides, but that they won’t vote. Evangelical disillusionment with George W. Bush in 2000 arguably cost him a majority. A lack of enthusiasm among many blacks for 2004 Democratic nominee John Kerry kept black turnout at lower-than-expected levels.

What’s happening in the unfolding 2016 campaign is the rise of identity politics. Thanks to social media, it’s now easier for like-minded interests or communities to organize and apply pressure on behalf of their special interests, often advocating rigid ideological responses to vexing problems.

That makes it tougher to build traditional political coalitions, let alone govern, since such efforts require those blocs to accept less than 100 percent of their agendas.

“People think the imperative of building broad coalitions is less important than demanding validation for their views,” said Will Marshall, president of the Progressive Policy Institute, a centrist Democratic research group.

Much of the black community has a host of non-ideological though unique concerns. The first African-American president is leaving office. There’s been uneasiness for years that Democrats assume they’ll get their usual overwhelming general election margin and therefore can concentrate on wooing swing white voters.

Most worrisome is a widespread feeling that black communities’ struggles with police have gained national attention, yet white politicians still don’t get it. Last year’s shooting of a black teenager by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo., the death at the hands of police of Eric Garner in New York City, and this year’s riots in Baltimore after the death of Freddie Gray in police custody were all major news events.

“This has entered into people’s consciousness like it hasn’t before,” said Karen Dolan, director of the Criminalization of Poverty project at the Institute for Policy Studies, a liberal research group.

That’s why social media erupted in protest when Clinton, speaking last month at a church a few miles from Ferguson, spoke about how her mother believed “all lives matter.” The African-American community was still reeling from the Michael Brown shooting, and black activists were aghast at her comment, even though it wasn’t mentioned in the context of race.

The Clinton campaign is responding by citing her December speech in New York City where she said, “Yes, black lives matter.” In April, two days after the Baltimore riots, she used her first major campaign speech to outline a plan for criminal justice reform.

Thursday, during a stop in West Columbia, S.C., Clinton said there still are not enough jobs, the criminal system is “out of balance,” and African-American men are “far more likely to be stopped and searched” and serve longer prison terms.

Last week, Clinton’s rivals felt the activists’ sting. Protesters shouted “Do black lives matter to you?” as O’Malley spoke at Netroots Nation, a liberal conference. O’Malley tried to respond and talked about his record as mayor of Baltimore.

“Black lives matter. White lives matter. All lives matter,” he said. Booing erupted. O’Malley, who as mayor of Baltimore was criticized among many blacks for his crackdown on even minor crime, left the stage.

Next up was Sanders, long a hero of liberal activists. “Black lives matter,” Sanders said. “But I’ve spent 50 years of my life fighting for civil rights.” The next day, BernieSoBlack was trending on Twitter, as users mocked him even as some praised his liberal leanings. The critics’ point: There’s a lot of work yet to do.

The concern was not strictly political, said Patrisse Cullors, co-founder of Black Lives Matter, a movement seeking more attention for police-community issues. “If there’s a crisis in this country, you don’t ignore it,” she said.

O’Malley tried quickly to respond, apologizing and explaining his views. He tweeted Monday: “I’m not done listening.”

Many activists aren’t satisfied. Cullors wants to see more sensitivity and dialogue about issues of notable interest to the black community, notably criminal justice reform, police-community relations, education and income inequality. And stay away from saying “all lives matter.”

For political parties, this rush to ease the activists’ concerns creates a potential image problem, whether specific constituencies will appear to have a stranglehold on them. For years, presidential candidates won by delicately balancing loyal blocs, promising each just enough to satisfy them but not so much that it looked like pandering.

Today, the building blocks are different, as like-minded communities can more easily band together not only with ideology but identity. In 2012 and 2014, Democrats tried to piece together coalitions of single women, blacks, Latinos and white liberals, often stressing support for abortion rights, a path to immigration, more funding for social programs and support for gay marriage. Republicans built their own networks with positions that often promised the opposite.

The danger in this identity politics is that those who don’t feel part of any group feel abandoned. And winning with these new kinds of coalitions can make it harder to govern, since there’s often no unifying theme that creates a single mandate. Not even saying “All lives matter.”

In this sort of environment, said Marshall, “It makes it hard to achieve political cohesion.”

Photo: Whose lives matter? Yasmeen via Flickr