The Democratic National Committee is moving ahead with plans to offer a telephone voting option during 2020’s first presidential contest, the Iowa caucuses, even though big questions remain about the system’s technology, security, and vote-counting procedures.

The DNC’s Rules and Bylaws Committee granted “conditional” approval to Iowa’s 2020 plan after spending two hours discussing the proposed “virtual caucus” system on June 28. The DNC staff highlighted their concerns and questions, ranging from a ranking of the top five candidates on the telephone ballot to the voting system’s technology and security. Top Iowa state party officials described and defended their proposal, expressing confidence in their likely vendors, prospective training, and other implementation details, but said they need the panel’s full approval before they can sign contracts and start building the actual customized system. Some Rules and Bylaws Committee (RBC) members—the party’s voting procedure experts—said that they need much more in-depth assessments before granting final approval.

“Is there any anticipated go/no-go date with the technology itself?” asked RBC member Yohannes Abraham, from Virginia, before the panel voted to give Iowa a month to work with DNC staff and return with answers. “This strikes me as not a simple thing to stand up, and there will be a point at which we’re game-time ready or not.”

Top Iowa party officials replied that they had been working with vendors to design a system to increase participation by offering a remote voting option, but that they were not making contingency plans because they are anticipating its successful deployment.

“We’ve had enough conversations with at least a couple of vendors that they are very confident that they can do this process because they’ve done much larger versions of this process,” replied Scott Brennan, an RBC member from Iowa and former state party chair. “We don’t anticipate there will be the need to have a go/no-go date, because we’re making unique changes to the Iowa caucuses, but the process that we are using is not necessarily earth-shattering.”

Some RBC members were skeptical, however. Many had lines of questioning in three areas flagged early by longtime DNC member and party lawyer Harold Ickes, from Washington, D.C., about “system overload,” “security” and “counting.” As former DNC chair and ex-presidential campaign manager Donna Brazile said midway through the discussion, the party is undertaking a daunting task.

“This is the most interesting proposal I’ve seen in my 20-plus years on Rules and Bylaws,” Brazile said. “I must tell you, it is as complicated as it appears on paper. So I am not ready yet. I’m concerned about the safeguards. And I’m also worried that we don’t have enough time to get to this point in 2020. This is the future, but I don’t know if we are there yet.”

But other RBC members were less perturbed, saying the still-developing caucus state plans were to be expected—from Iowa, and from Nevada, 2020’s third contest and one whose proposed off-site voting system is more complex than Iowa’s plans.

The DNC’s Unity Reform Commission created after 2016’s controversial nominating season directed that steps be taken to increase voter participation. That instruction led to the RBC’s 2020 Delegate Selection Rules issued in late 2018, which required that a new remote voting option be offered in caucus states, and that a paper trail of the voting be created in those states—in case the results are challenged and a recount ensues.

“I do want to reiterate that Iowa is doing this because we basically told them to,” said New Hampshire’s Kathleen Sullivan. “You [fellow RBC members] might want to keep that in mind.”

Iowa Presents Still-Developing Plans

The Rules Committee’s agenda at its June meeting was to review plans by 22 states to elect delegates to the party’s 2020 national convention, where the presidential ticket would be formalized. Three states were holding caucuses, which is not the same as primary voting.

Caucuses are like traditional New England town meetings where citizens gather, make speeches, and vote. Those present employ rounds of voting, where a candidate must surmount elimination thresholds (15 percent of the vote in the room) to stay viable, in contrast to winner-take-all balloting in primary elections. This process ends when no candidate has less than 15 percent of the total vote. Depending on the resulting percentages, the precinct caucus will then allocate a set number of delegates representing those candidates to the next stage in the process: Iowa’s county conventions. In between the voting rounds, the campaigns try to persuade voters to switch from their initial choices.

In 2020 the Democrats’ caucus states will include Iowa, which opens the nominating season on February 3; Nevada, which is third, comes on Feb. 22; and Alaska in April. Unlike most primary elections, which are run by government election officials, the state parties run caucuses and rent the voting system from vendors.

“Our goal is simple: to address the challenges that we knew exist in our process while preserving the spirit of the Iowa caucuses,” said Iowa’s Brennan, in a 20-minute opening presentation. “The plan before you does exactly that. Included in this plan will be the most significant changes in the Iowa Democratic Party caucuses since its inception in 1972. These changes will make the 2020 caucuses the most accessible, transparent and secure caucuses ever.”

“On caucus day, precinct caucuses in all 1,677 precincts [across Iowa will be] almost unchanged from the experience of the past 48 years,” Brennan said, emphasizing that most 2020 participants would not be voting remotely—but in precincts. But, for “those previously excluded—shift workers, single parents, people with disability or mobility issues, people working out of state or serving overseas—and others,” there will be six sessions of “virtual” or phone-based voting caucuses, where people who register beforehand can vote in varied time slots.

“During the virtual caucus, participants will find it similar to a precinct caucus,” he said. “Participants will find how to get more information on the candidates, the chance to be a delegate at the district or state level or an alternate to the [party] convention, and instructions on how to submit platform planks. And rank the top five choices for president, compared to [in-person caucuses and] precinct choices where people will rank their top two.”

The Iowa party envisions that people who want to vote early or by phone will register by mid-January. Registration will be online, as many states now handle voter registration. These voters will get an email with instructions and credentials—including PIN numbers—to access the phone-based voting system. Once inside that system, the voters will be presented with 23 candidate choices (the current number) and asked to rank their top five using their keypad.

The party has not said what kind of remote interface voters will use. It generally has called the process a “tele-caucus,” meaning one would listen to recorded instructions and type in numbers to make choices—as one might pay a bill over the phone. But hints were dropped that voters with other digital devices, such as smartphones or tablets connected to cellular signals or the internet, also would be able to use them. Brennan said there would be options for “real-time closed captioning, as well as language translation [and] ESL [English as a second language] interpretation for those that request it.” In other words, the system may work with older push-button landline phones, but it could offer features supported by a smartphone app or webpage—which is online voting. Those technical details were envisioned, not yet finalized, he said.

“We are still going through our RFP [request for proposal] process to determine the vendors who will be instrumental in making this process happen,” Brennan said. “Once that [process] is complete, we will be able to further determine exactly what the registration process, the order of events and the [count and delegate allocation] reporting will look like. Also, we will be able to build the security protocols around these systems for greater protection around hacking and outside bad actors.”

As Iowa Democratic Party Executive Director Kevin Geiken elaborated after the committee review, the system will have four main technical components. “There is the registration process,” he said. “There is the technology of hosting that small pool of people on a virtual caucus system, where they have to press certain numbers to get certain results. There’s the third challenge of being able to tabulate those votes in a way that follows our [candidate ranking and proportional representation] rules. The fourth is how do we project all of those [new features and results] out into the world. Some vendors play in one or two of those buckets.”

Brennan told the RBC that the state party has no credible way to estimate how many people would actually use the remote voting option, even though it had consulted with a range of experts. The past estimates have suggested one-quarter or more of 2020 caucus participants might vote remotely.

Brennan and Geiken turned to the vote-counting process and said that the state party decided that it would be simpler to create four new statewide precincts for telephone voters—one for each of Iowa’s U.S. House districts—where the virtual votes would be separately tallied, and then added to the statewide results from the precinct caucuses to determine the night’s winner: the candidate with the most delegates awarded to the process’s next stage. The virtual bloc would be allocating 10 percent of the delegates statewide.

The challenge before the Iowa party was to create a remote voting process that closely copied what occurs in the physical caucuses, the Iowa officials said. The solution is to have a version of what was called a ranked-choice ballot, where telephone voters will list their top five candidates. Geiken said that somewhere among the voter’s top five choices was likely to be one candidate who was viable and crossed the 15 percent elimination threshold.

Geiken noted that the party was “working with vendors to see if it’s possible to send voters back an email receipt” of their choices, which one RBC member, David McDonald of Washington state, questioned as possibly not satisfying the Rules Committee’s 2020 requirement for a paper-based vote count audit trail—for possible recounts. Geiken and Brennan also explained that participants at the 1,677 caucus sites would fill out a paper form—not a ballot—that listed their first and final presidential choices, which would comprise a paper record of the precinct voting.

Security and Ranked-Choice Voting

The most vocal RBC members raised concerns about the intricacies of this overall process—such as what were the plans for collecting all of those presidential preference cards from the 1,677 precincts in a manner where none would be lost or suddenly appear in a close or contested vote. But, overall, the two main areas of concern were the virtual system’s security and its ranked-choice voting.

On the cyber-security front, Virginia’s Abraham was not the only RBC member to ask about backup plans, in case something forced the Iowa party to shut down the virtual voting process.

“You get up to the last day, when you have a virtual and actual [precinct caucuses] happening at the same time—what code red activities do you have in place if everything falls apart?” asked Yvette Lewis of Maryland. “What do you have in case the system breaks down, or something goes screwy? I think you need a code red contingency in case things fall apart on the last day.”

“We are spending a lot of time talking about the virtual caucuses, but it is my belief that the majority of Iowans will participate in the caucuses like they always have,” replied Brennan. “It is a smaller universe of people that will participate in the virtual caucuses.”

“I get that,” Lewis countered. “But I think we are spending so much time on it because it is new and we need to work out all of the bugs in it now… All of the other parts you have done before… [are] like walking in your sleep. This isn’t. It is something that can skew the numbers. We need to flesh this out.”

Lewis and Abraham were not alone in expressing big-picture reservations as more details emerged about operating a new system of remote voting and allocating presidential convention delegates.

“We are being asked to certify that the party has the technical ability, the skill, the expertise, the finances, and all these security issues will be in place, and nobody will be disenfranchised, and whether there’s a red plan,” said RBC member McDonald after the previous exchange. “I am reluctant to give a carte blanche out of here and say, ‘Yeah, it’s all okay, trust it.’”

These concerns surprised Iowa officials. They said that they expected to win full RBC approval, which they say they needed before signing any contracts with vendors who will build and customize the actual voting system. They also noted the DNC’s 2020 rules never specified creating a backup system.

There were also more customer-service oriented questions about whether voters using the telephone system for the first time could become confused by the volume of the choices and ranking them.

“I’m not sure how it would really work,” said Frank Leone, an RBC member from Virginia. “Currently, there are 23 candidates. So how do you—does the [pre-recorded telephone] vote listing list all 23 candidates, and then you put in the number 12 or something, and then you do this five different times, and somehow it all gets put together at a statewide level, and then re-sorted five different times to come up with results? It seems to… create a great deal of confusion and effort, certainly on your part and on the part of the voter, who is trying to call in and negotiate somehow.”

“From my perspective as a prospective voter, how do you plan to translate all of this to the public?” RBC Co-Chair Lorraine Miller of Texas asked immediately after Leone’s question and remarks. “Give us a little synopsis at the end of the presentation.”

Geiken responded that the party’s messaging would be simple.

“It’s really less about what are the changes in the process and more so from a perspective of ‘how can I participate in the caucus?’ That is a relatively easy answer,” he said. “Every Iowa Democrat who wants to caucus should caucus. If you want to caucus on February 3 and you are available and able to caucus in person, you show up to your caucus site.”

“If you can’t go on February 3 and want to participate virtually, here’s how you do that. You register with us somewhere between January 6 and January 17,” he continued. “At the point of registration, you get the instructions, access code, some other security questions. You call into that caucus session… rank candidates, then [answer] party business questions… That is [how] the simplicity of the process for the Iowa caucus goes.”

The public education would emphasize the process’s positives, not negative “what-if” scenarios, Geiken said.

“We don’t have plans to talk into the weeds, all of the scenarios,” he said. “If you are participating virtually and your phone dies halfway through, what do you do? Well, some people may want to know that. So we will have that on our website—all of what we will call ‘caucus what-ifs—frequently asked questions.’ And then from there be aggressive with pushing this information out with our partners [constituencies, campaigns], including the media.”

As the review neared the two-hour mark, it occurred to the more outspoken RBC members—a few out of two-dozen in the room—that the panel did not have sufficient explanations, or possibly the technical expertise, to assess some key unanswered concerns.

“We are not really doing the job that we have been asked to do,” said McDonald, referring to vetting the virtual voting. “We need a complete plan. Our [DNC] security people need to have seen the vendors, to make sure that they are actually able to comply with the security. Unless somebody says that can be done by [the late] July [RBC meeting], I’d suggest August, at least.”

At this point, the RBC co-chairs, Lorraine Miller, and James Roosevelt III of Massachusetts, noted that the DNC technical staff had recommended “a conditional compliance” for Iowa and began the formal process to proceed to committee endorsement vote.

“We can agree that the plan meets the spirit of the DNC rules, but has open questions that need to be resolved,” said Roosevelt. “Technical questions can be addressed by staff. Questions that are more than just technical are always brought to the co-chairs, and then we decide if it needs to go back to the committee. By conditional compliance, we endorse the framework of the plan but [are] not giving final approval to its implementation.”

“My concerns are not just technical,” interjected McDonald, who then cited the ranked-choice voting method for telephone voters, and only allocating that bloc 10 percent of the overall delegates. “Whether allocating those results only to a congressional district, as opposed to back to a precinct where the person was supposed to vote, is fair. And I do not want, by this vote of conditional compliance, to say that those things comply.”

Roosevelt agreed with McDonald, and also acknowledged that the Iowa party officials looked disappointed. “I can maybe sense by the look on your faces that you’re saying, ‘but what else?’ But, between now and then, we will ask you to see what else,” he said. “And then we’ll see… can we vote for compliance?”

“My only suggestion, for any number of reasons, [is] we need to be done with the process in July,” Brennan replied. “Whatever those issues are, we need to have them outlined for us within the next week. We can address all of those issues… if we take it to August, we’re too late.”

“I think what we’ve done today is you’ve brought forth a great deal of information, and we have satisfied some concerns—and some that are not fully satisfied,” Roosevelt said. “We know this is a big deal. That’s why we spent so much time today… We will have what we are dealing with at the July meeting.”

After that exchange, the Rules Committee conditionally approved Iowa’s plans. The biggest issues were if the proposed virtual voting system elements would be secure enough for the DNC’s security team. And would the allocation of delegates after the telephone-based ranked-choice voting have to be changed—and with it the underlying technology—so virtual votes are added into precinct results? (Allocating virtual votes locally is Nevada’s approach.)

“I don’t know that we are set back. We will have to see what the staff review comes back with next,” said Geiken afterward. “If the committee says we have to inject it [virtual voting results] into the precinct level, that significantly changes our timeline… That would significantly change the relationship with our vendor and the product we are asking for.”

“I think they [the RBC] will find that when they talk to Nevada and any other state, I think they will find that we are not any farther behind; in fact, we are farther ahead of the game in thinking of the security concerns, the actual technological solutions that are needed, than any other state right now,” Geiken said. “For all of the members, this is the first time looking at any of this… That’s not a slight on any other state. I think Nevada is quite far—they have gone down the rabbit hole as we have on this. We were, in fact, the test case in today’s conversation.”

(Editor’s note: This is the first report in a series on new technologies and voting procedures that might be used in the 2020 presidential election’s opening contests. The next report will look at Nevada’s proposed virtual caucus voting system.)

Steven Rosenfeld is the editor and chief correspondent of Voting Booth, a project of the Independent Media Institute. He has reported for National Public Radio, Marketplace, and Christian Science Monitor Radio, as well as a wide range of progressive publications including Salon, AlterNet, The American Prospect, and many others.

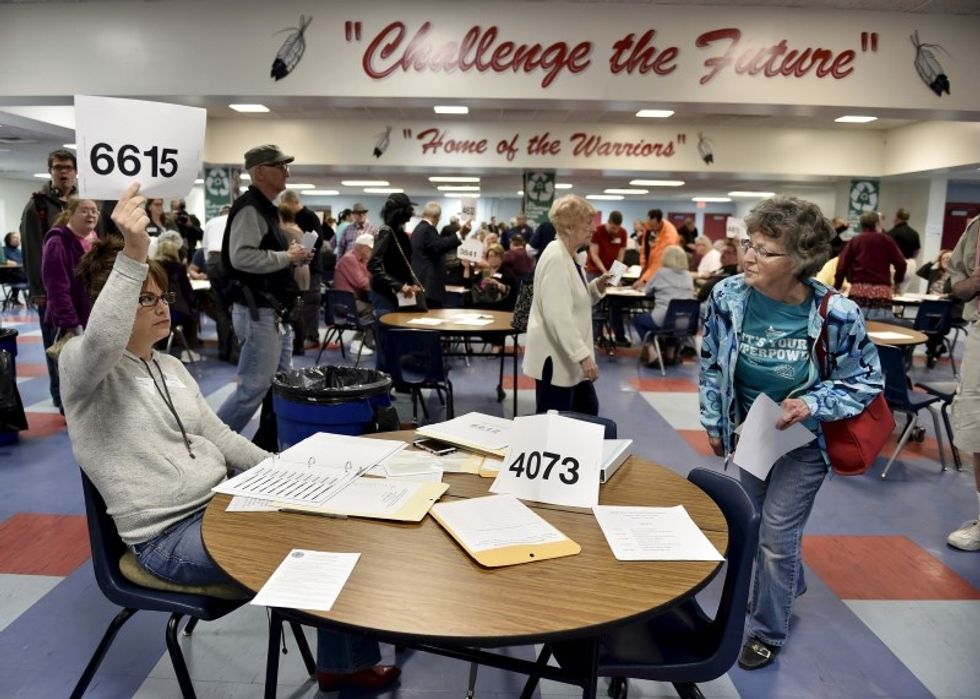

IMAGE: A caucus worker holds up a sign to direct voters to their respective table during Nevada Republican presidential caucus at Western High School in Las Vegas, Nevada February 23, 2016. REUTERS/David Becker