By Dave Helling, The Kansas City Star

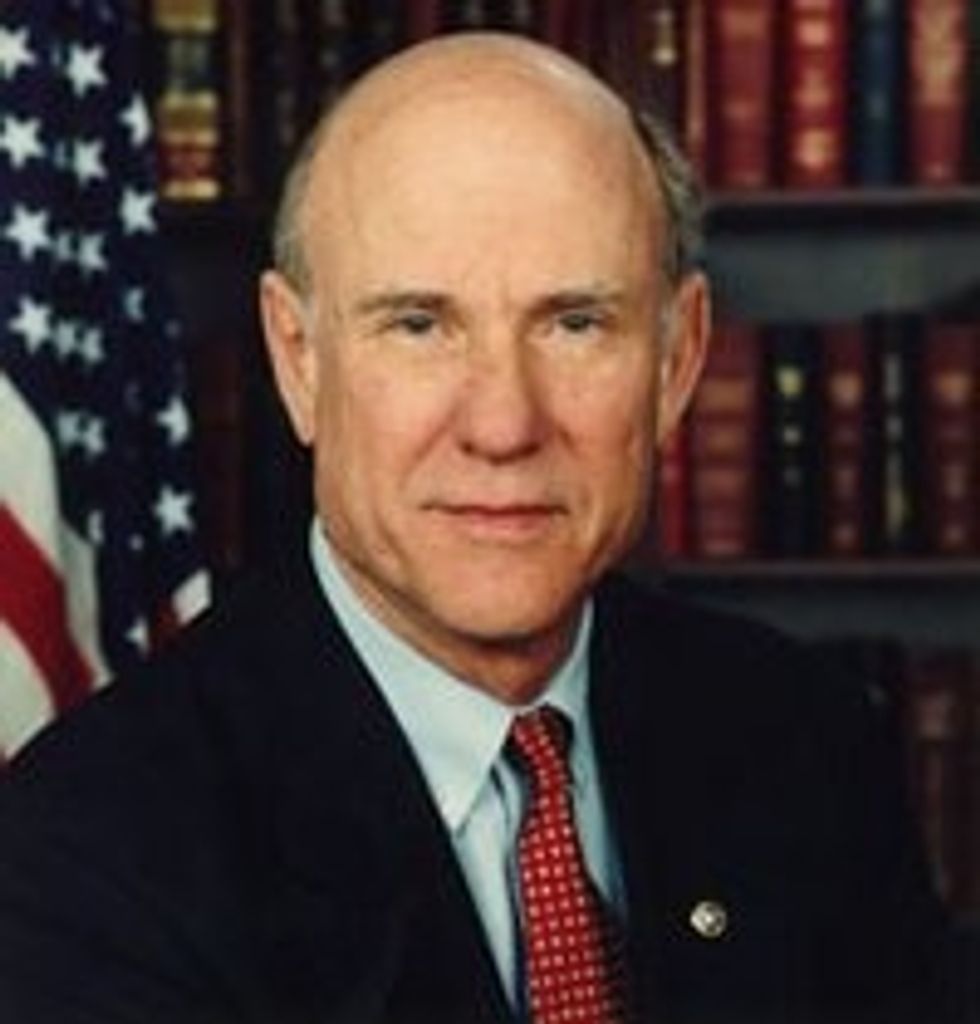

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Sen. Pat Roberts sits in a Lenexa, Kan., fast-food restaurant, spooning ice cream from a cup.

It’s already been a long day. That morning, the 78-year-old Republican braved the heat of the Lenexa July Fourth parade; after lunch, he would be shaking hands at the VFW hall down the street.

Then on to Wamego, Kan., for another parade. Then Hays, Kan. Then another town, another campaign appearance, another search for votes.

It’s tough and familiar political terrain — Roberts has spent the better part of three decades running for office. If Kansas returns him to the Senate this year, he’ll rank among the longest-tenured public servants in the state’s history.

Does he ever think about stepping aside to give someone else a chance?

Roberts’ face grows red below his Marine Corps ball cap. The ice cream softens.

“Why on earth would I not run, if I feel good (and) the people are for me?” he asks.

“The years have got nothing to do with it.”

The years, of course, are the biggest issue in the campaign.

Roberts was first elected to the U.S. House in 1980, from the sprawling 1st District, after then-boss U.S. Rep. Keith Sebelius walked away from the seat.

Roberts quickly carved out space as a sometimes prickly GOP moderate, focused largely on agriculture. He worked to persuade Ronald Reagan to lift an embargo on grain sales to the Soviet Union, while striving to protect generous farm subsidies and agri-business autonomy.

On most other issues, Roberts was a reliable Republican vote. After the GOP won control of the House in 1994, he claimed his reward: chairmanship of the Agriculture Committee, the pinnacle of his time in the House.

But it didn’t last long. In 1996 Roberts sought Nancy Kassebaum’s empty Senate seat, winning easily. He’s been re-elected twice, rising to the chairmanship of both the Agriculture and Intelligence committees.

Both assignments caused him headaches.

In the House, Roberts had engineered an overhaul of farm policy with a bill called Freedom to Farm, a measure designed to slowly withdraw taxpayer support for agriculture. Just a few years later, it was widely seen as a failure — and Roberts, then a senator, had to watch as it was largely dismantled.

And he was fiercely criticized for his work on the Intelligence Committee. Democrats accused Roberts of covering up the mistakes of the George W. Bush White House, an accusation he just as fiercely rejected.

For all the successes and failures, though, Roberts’ resume ordinarily would entitle him to a victory lap this year: an easy primary, perhaps token Democratic opposition.

That was pre-tea party. GOP primary challenger Milton Wolf has mounted a serious insurgency, based almost entirely on criticism of Roberts’ years in the nation’s capital.

In contemporary government, national experience can be a decidedly mixed blessing.

“Pat Roberts does things the Washington way,” Wolf says. Exhibit A? Roberts’ residence.

In February, the senior senator told The New York Times he had no permanent home in the state — his Dodge City house was rented out, Roberts said, while he claimed a Kansas voting address at the home of a longtime supporter. Wolf pounced, and hasn’t let up since.

Roberts bristles at the suggestion he isn’t really a Kansan. At the same time, he admits he’s spent most of his political career raising his family in the suburbs of Washington, D.C.

“I would never have seen my kids,” he explained. “It was hard enough (in) Virginia. But had I been in Dodge City, I would have gotten there Friday evening, and … (then) Saturday morning: ‘Bye kids, I’ve got to go all around the district.’ I didn’t want to do that.

“Back in that era, people expected you to be in Washington to do your job.”

In May, a three-person board in Topeka rejected a challenge to Roberts’ claim of Kansas residency and certified him for the ballot.

He clearly owns property in other places — Roberts’ wife, Franki, sells real estate in Virginia, and property ownership is the foundation of the couple’s wealth.

Roberts’ personal financial disclosure statement for 2012 shows ownership of a condominium in Alexandria, Va., worth between $500,000 and $1 million. It also shows a condominium in National Harbor, Md., valued between $250,000 and $500,000, and the Dodge City home, valued between $100,000 and $250,000.

Roberts claims rental income from all three properties.

His 2012 net worth, the Center for Responsive Politics says, was between $850,029 and $2,540,999, not including the Virginia house in which he lives.

By contrast, Roberts’ financial disclosure for 1982 — his second year in Congress — claimed holdings valued between $20,002 and $65,000. The listing included half-interest in a vacant lot in Dodge City.

Roberts’ home and his Washington tenure have dominated the 2014 primary largely because few political issues separate the two major GOP competitors.

Milton Wolf admits this. “Do you know how many issues Pat Roberts will claim I’m wrong on?” he said in March. “Not a single one.”

Indeed, on issue after issue, Roberts has cast votes and made statements designed to please the strongly conservative voters who often dominate GOP primaries.

He was among the first politicians to call on Kathleen Sebelius to resign as health and human services secretary after the disastrous Obamacare rollout — even though Sebelius, daughter-in-law of Keith Sebelius, was a decades-old family friend. Roberts had supported her during the confirmation process.

Roberts opposed the last farm bill. He opposed a spending bill that included significant funds for the National Bio- and Agro-Defense lab in Manhattan, Kan. In 2012, he voted against a vague resolution on a U.N. disability treaty — while mentor and resolution supporter Bob Dole watched from a wheelchair.

He’s aligned himself with conservative Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas during battles over the debt ceiling and the budget, although Roberts has supported extensions of the debt ceiling in the past.

Roberts has worked hard on the politics of his re-election as the issues.

He’s cornered endorsements from all of the state’s prominent Republicans: Gov. Sam Brownback, Secretary of State Kris Kobach, all four House members from Kansas.

Roberts has easily outraised and outspent Wolf. For this election cycle, Federal Election Commission filings show, Roberts has raised $4.4 million to Wolf’s $897,000.

For all the endorsements and cash advantage, though, Roberts appears to think his strongest re-election argument is the very thing Wolf calls his Achilles’ heel — experience.

“I’m not intending to be in the Congress forever,” Roberts said.

But “if you have the experience, and you have the people of Kansas behind you, and you know specifically what you want to accomplish, and you have the seniority to make it happen — no other candidate can do that, except me.”

Photo via WikiCommons

Interested in U.S. politics? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!