The 1990 Supreme Court Decision That Could Protect Trump's 'Big Lie'

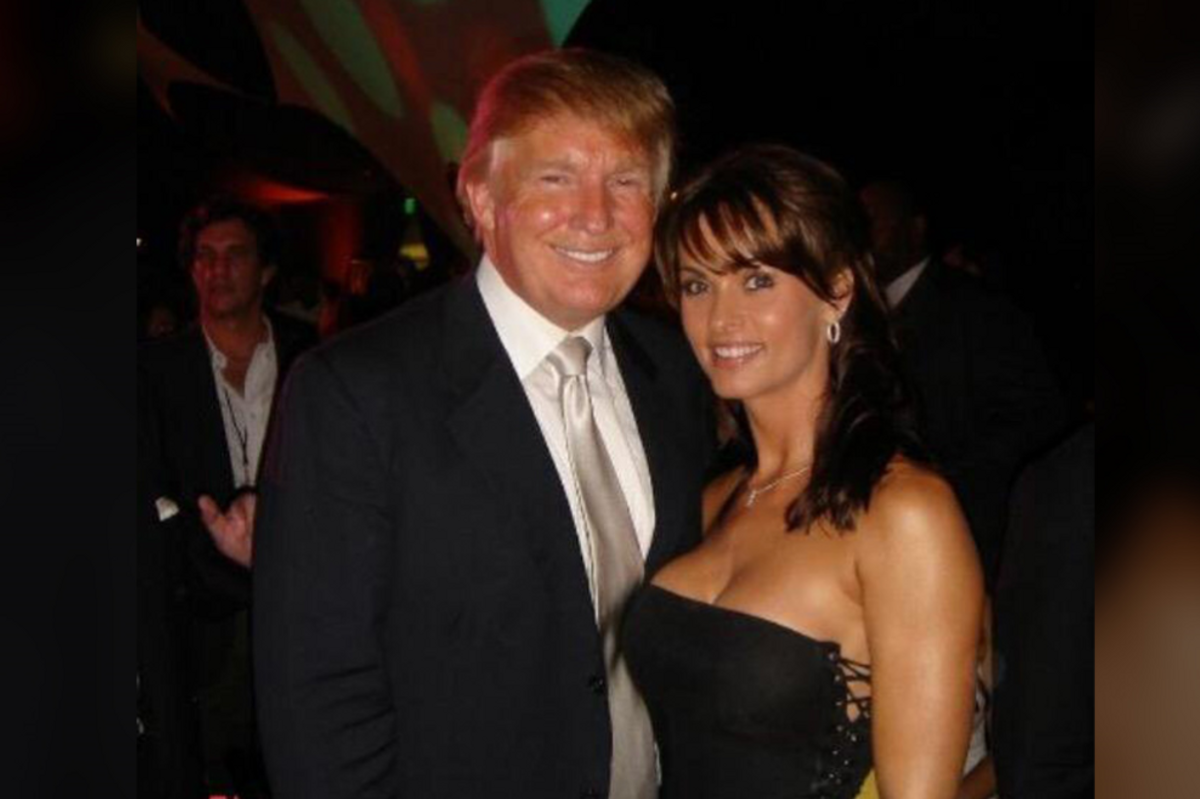

Donald Trump and Karen McDougal

During the past week, members of the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the Capitol spent hours detailing the crimes that led up to the riot that ransacked the Capitol building on that first Wednesday of January 2021. The exhibits included testimony from witnesses, copies of written communications, and video clips posted by the rioters showing how they interpreted the reporting of events.

What none of the committee members mentioned was the role that a 1974 midwest melee played in the proceedings. The conditions that would allow former President Donald J. Trump to foment an insurrection that snatched the lives of four civilians and five police officers and injured scores more started their development in an Ohio wrestling match almost 50 years earlier.

At a February 9, 1974 wresting match, Maple Heights High school wrestling star Bob Girardi didn’t want to accept loss; he hit his opponent from Mentor High School. The punch exploded into a mess of violence that sent four Mentor High School wrestlers to the hospital. No one was criminally charged for the riot, but the Ohio High School Athletic Association barred Maple Heights High School — a nine-time state champion — from participating in the next state championship. To get a chance to stay champs, Maple Heights High School sued, leading to a hearing that required the school’s head wrestling coach, Michael Milkovich, to testify.

The day after the hearing, Tim Diadiun, a local newspaper columnist, wrote a column headlined “Maple Beat the Law with the ‘Big Lie’” and accused Milkovich of lying under oath about what happened at the match in order to slide back into contention; Diadiun had been present and witnessed what he saw as Milkovich fomenting the fracas. Milkovich sued Diadiun for libel and the case took 16 years to reach the Supreme Court of the United States as the case of Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Company.

Diadun had the advantage at the high court because, twenty years earlier, American Opinion, a publication of the John Birch Society, ran an article that named Elmer Gertz, a well-known Chicago attorney who represented a police shooting victim’s family against the officer, and called him a Communist with a criminal record. The American Opinion editor published the “Communist” and “convict” labels without verifying them; the editor admitted he relied on the reputation of the author for their accuracy. Attorney Gertz sued for libel and won $50,000 from a jury but the judge set aside the verdict.

After many appellate wranglings, Gertz eventually won $400,000 in compensatory and punitive damages. One of those appellate stops was at the U.S. Supreme Court, where Justice Powell wrote of Gertz’s claim: “Under the First Amendment there is no such thing as a false idea. However pernicious an opinion may seem, we depend for its correction not on the conscience of judges and juries but on the competition of other ideas.” Because of this holding, Diadiun and the other defendants were likely going to prevail at the Supreme Court; the Gertz Court extended refuge to falsehoods, saying some of them deserved protection under the First Amendment “in order to protect speech that matters.”

In other words, it actually didn’t matter what the columnist wrote; as long as it was labeled opinion, it was protected. States and lower courts didn’t like this; they interpreted the Gertz decision as creating privilege tantamount to “a wholesale defamation exemption for anything that might be labeled 'opinion.”

Diadiun lost because the Supreme Court set out to change that rule in the Milkovich case. The Supreme Court explicitly rejected blanket protection for any article labeled opinion when Chief Justice William Rehnquist, writing for the majority, said the Gertz decision never intended that comprehensive exception “since "expressions of 'opinion' may often imply an assertion of objective fact.”

It seemed like a win for accurate journalism and public opining, but it ultimately wasn’t.

On one hand, the Milkovich decision narrowed the First Amendment shield for opinion writers; they must write the truth, a reasonable requirement. As long as those facts within an opinion piece aren’t “provable as false” — meaning the language cannot be proved true or false by a core of objective evidence — a statement is constitutionally protected. This category of non-provable opinion includes subjective beliefs based on true facts.

On the other hand, the Court limited free speech protections, saying that statements that “cannot reasonably [be] interpreted as stating actual facts” — meaning “loose, figurative, or hyperbolic language which would negate the impression that the writer was seriously maintaining” an actual fact, or where the “general tenor of the article” isn’t to be believed — are also protected. At the time of the decision, Jane E. Kirtley, a lawyer and executive director of Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, predicted disaster to the New York Times. The decision, she said, “ironically is going to encourage irresponsible commentary at the expense of well-reasoned analysis.”

Kirtley was right. Crazy claims — like China or Italy interfering in our 2020 election through wifi or the late Hugo Chávez maneuvering a Democrat into the White House from the grave — ultimately get protection (no one’s litigated these claims) because no reasonable person would ever believe them.

Attorneys for the former president and right-wing media stars avail themselves of theMilkovich defense in courtroom wrestling matches, claiming that the content in question may be false, but it’s not actionable because it isn’t believable. They started with softball cases. When Stephanie Clifford, a woman who credibly claimed to have had an affair with Donald Trump, sued him for calling her a “con job” in a 2018 tweet, the court held, citing Milkovich, that “...it would be clear to a reasonable reader that the tweet was not accusing Clifford of actually committing criminal activity.”

The Milkovich holding helped Fox News host Tucker Carlson defeat a defamation claim filed by Karen McDougal, the model who said she had an affair with Donald Trump. McDougal alleged Carlson defamed her when he described her request for money to keep her story quiet as the crime of “extortion.”

But the most recent use of Milkovich is a big-league problem and the most disturbing; it’s been used to prop up not the ‘Big Lie’ that Tim Diadiun wrote about in 1974, but the Big Lie about the 2020 presidential election. Lawyers pulled the case out when Dominion Voting Systems filed defamation claims against Fox News in 2020 for reports that their machines miscounted votes in favor of then-candidate Joseph Biden. Fox lost a motion to dismiss the lawsuit under the Milkovich defense, but the court will still hear the case on its merits and the defense can pop up again and succeed, barring any other settlement or resolution.

Just like it did in 1974, an unwillingness to accept defeat and inartful grappling with facts conspired to create a brawl, one that would take years to dissect, understand, and resolve. Through the Milkovich decision, that insistence on a win and the events that followed it brought the country to the brink of a coup -- but not because the Supreme Court justices didn’t care about the truth.

Both the Sullivan and Milkovich courts had a faith in the public's capacity to discern factual falsehoods that we don’t — or at least we shouldn’t — today. Both courts thought that inaccuracies deserve constitutional protection because the general public is responsible enough to both assess and improve the flow of information on matters of public concern. But it’s not.

We’re not that responsible, as this week’s hearings demonstrated. The ability of the "marketplace of ideas" ability to adequately determine facts depends on the “reasonable reader” or consumer of news. That isn't what happens anymore. Judging by the videos of Capitol rioters shown during the hearing this week, rather than that reasonable reader acting as a check on lies and disinformation, unreasonable readers respond to unreasonable speakers and put American democracy at risk.

Chandra Bozelko did time in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent, and she later established a blog under the same name that earned several professional awards. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.

- Opinion | The recklessness of Tucker Carlson - The Washington Post ›

- Karen McDougal Sues Fox News Over 'Extortion' Claim - Variety ›

- Fox Wins McDougal Case, Argues No One Takes Tucker Carlson ... ›

- The Legal Defense For Fox's Tucker Carlson: He Can't Be Literally ... ›

- Opinion and Fair Comment Privileges | Digital Media Law Project ›

- Is your speech protected by the First Amendment? | Freedom Forum ... ›