This Labor Day, Remember That Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign Was For Workers’ Rights

Reprinted with permission fromCommonDreams.org

Most Americans today know that Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in Memphis, Tennessee in 1968, but few know why he was there. King went to Memphis to support African American garbage workers, who were on strike to protest unsafe conditions, abusive white supervisors, and low wages — and to gain recognition for their union. Their picket signs relayed a simple but profound message: “I Am A Man.”

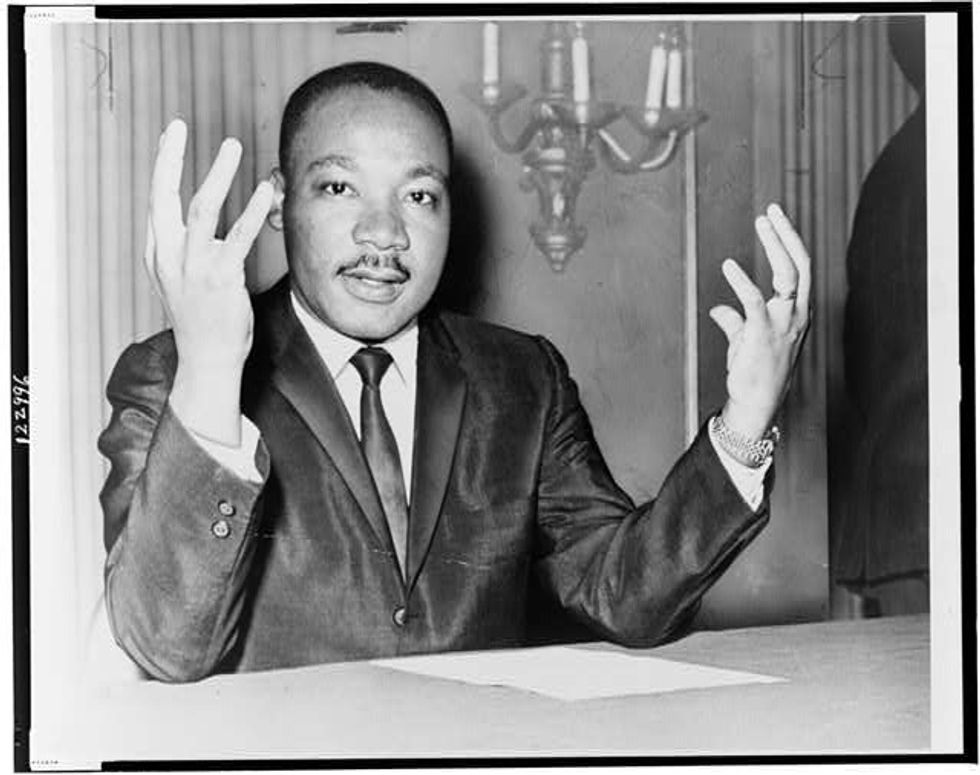

Today we view King as something of a saint, his birthday a national holiday, and his name adorning schools and street signs. But in his day, the establishment considered King a dangerous troublemaker. He was harassed by the FBI and vilified in the media. He began his activism in Montgomery, Alabama, as a crusader against the nation’s racial caste system, but the struggle for civil rights radicalized him into a fighter for broader economic and social justice.

As we celebrate Labor Day on Monday, let’s remember that King was committed to building bridges between the civil rights and labor movements.

Invited to address the AFL-CIO’s annual convention in 1961, King observed:

“Our needs are identical with labor’s needs: decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old-age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children, and respect in the community. That is why Negroes support labor’s demands and fight laws which curb labor. That is why the labor-hater and labor-baiter is virtually always a twin-headed creature spewing anti-Negro epithets from one mouth and anti-labor propaganda from the other mouth.”

He added:

“The labor movement did not diminish the strength of the nation but enlarged it. By raising the living standards of millions, labor miraculously created a market for industry and lifted the whole nation to undreamed of levels of production. Those who today attack labor forget these simple truths, but history remembers them.”

Several major unions reciprocated King’s support. When he was jailed in Birmingham for participating in civil disobedience, it was Walter Reuther, the charismatic leader of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union, who paid his bail.

Several major unions, especially the UAW and the International Ladies Garment Workers, had donated money to civil rights groups, supported the sit-ins and freedom rides, and helped organize the massive 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

We often forget that its official name was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and that its manifesto called on Congress not only to pass a civil rights bill but also “a national minimum wage act that will give all Americans a decent standard of living.” The manifesto pointed out that “anything less than $2.00 an hour fails to do this.”

In 1963, the minimum wage was $1.25 — the equivalent of $9.97 in today’s dollars. A $2 minimum wage in 1963 would be $15.95 an hour today.

In the 1960s, the sit-ins (a tactic adopted from workers’ sit-down strikes in the 1930s), Freedom Rides, mass marches, and voter registration drives eventually led Congress to enact the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. King was proud of the civil rights movement’s success in winning the passage of those important laws. But he realized that neither law did much to provide better jobs or housing for the large numbers of low-income African Americans in the cities and rural areas. He recognized the limits of breaking down legal segregation.

“What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?” King asked.

King observed: “Negroes are not the only poor in the nation. There are nearly twice as many white poor as Negro, and therefore the struggle against poverty is not involved solely with color or racial discrimination but with elementary economic justice.” To achieve economic justice, King said, “there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

“There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American whether he [or she] is a hospital worker, laundry worker, maid, or day laborer,” said King.

In a speech to the Illinois AFL-CIO in 1965, King said:

“The two most dynamic movements that reshaped the nation during the past three decades are the labor and civil rights movements. Our combined strength is potentially enormous. We have not used a fraction of it for our own good or for the needs of society as a whole. If we make the war on poverty a total war; if we seek higher standards for all workers for an enriched life, we have the ability to accomplish it, and our nation has the ability to provide it. lf our two movements unite their social pioneering initiative, thirty years from now people will look back on this day and honor those who had the vision to see the full possibilities of modern society and the courage to fight for their realization. On that day, the brotherhood of man, undergirded by economic security, will be a thrilling and creative reality.”

King warned about the “gulf between the haves and the have-nots” and insisted that America needed a “better distribution of wealth.”

Thus, it was not surprising that Memphis’ civil rights and union leaders invited King to their city to help draw national attention to the garbage strike.

The strike began over the mistreatment of 22 sanitation workers who reported for work on January 31, 1968, and were sent home when it began raining. White employees were not sent home. When the rain stopped after an hour or so, they continued to work and were paid for the full day, while the black workers lost a day’s pay. The next day, two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning city garbage truck.

These two incidents epitomized the workers’ long-standing grievances. Wages averaged about $1.70 per hour. Forty percent of the workers qualified for welfare to supplement their poverty-level salaries. They had almost no health care benefits, pensions, or vacations. They worked in filthy conditions, and lacked basic amenities like a place to eat and shower. They were required to haul leaky garbage tubs that spilled maggots and debris on them. White supervisors called them “boy” and arbitrarily sent them home without pay for minor infractions that they overlooked when white workers did the same thing. The workers asked Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb and the City Council to improve their working conditions, but they refused to do so.

On February 12, 1,300 black sanitation workers walked off their jobs, demanding that the city recognize their union (the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, AFSCME) and negotiate to resolve their grievances. They also demanded a pay increase to $2.35 an hour, overtime pay, and merit promotions without regard to race.

For the next several months, city officials refused to negotiate with the union. In private, Mayor Loeb reportedly told associates, “I’ll never be known as the mayor who signed a contract with a Negro union.”

The city used non-union workers and supervisors to pick up garbage downtown, from hospitals, and in residential areas. Even so, thousands of tons of garbage piled up. Community support for the strikers grew steadily. The NAACP endorsed the strike and sponsored all-night vigils and pickets at City Hall. On February 23, 1,500 people — strikers and their supporters — packed City Hall chambers, but the all-white City Council voted to back the mayor’s refusal to recognize the union.

Local ministers (led by Rev. James Lawson) formed a citywide group to support the strikers. They called on their congregants to participate in rallies and marches, donate to the strike fund, and boycott downtown stores in order to get business leaders to pressure city officials to negotiate with the union. On Sunday, March 3, an eight-hour gospel singing marathon at Mason Temple raised money for strikers. The next day, the beginning of the fourth week of the strike, 500 white labor unionists from Memphis and other Tennessee cities joined black ministers and sanitation workers in their daily downtown march.

On several occasions, the police attacked the strikers with clubs and mace. They harassed protestors and even arrested strike leaders for jaywalking. On March 5, 117 strikers and supporters were arrested for sitting in at city hall. Six days later, hundreds of students skipped high school to participate in a march led by black ministers. Two students were arrested.

At the rallies, ministers and union activists linked the workers’ grievances with the black community’s long-standing anger over police abuse, slum housing, segregated and inadequate schools, and the concentration of blacks in the lowest-paying, dirtiest jobs.

Despite the escalating protest, the city establishment dug in its heals, refusing to compromise and demanding that the strikers return to work or risk losing their jobs. The local daily newspaper, the Commercial Appeal, consistently opposed the strikers. “Memphis garbage strikers have turned an illegal walk out into anarchy,” it wrote in one editorial, “and Mayor Henry Loeb is exactly right when he says, ‘We can’t submit to this sort of thing!’”

Mayor Loeb and City Attorney Frank B. Gianotti persuaded a local judge to issue an injunction prohibiting the strike and picketing. The union and its allies refused to end their protests. Several union leaders — AFSCME’s international president Jerry Wurf, Local 1733 President T.O. Jones, and national staffers William Lucy and P. J. Ciampa — were cited for contempt, sentenced to 10 days in jail, fined $50, and freed pending appeal.

With tensions rising and no compromise in sight, local ministers and AFSCME invited King to Memphis to re-energize the local movement, lift the strikers’ flagging spirits, and encourage them to remain nonviolent. On Monday, March 18, King spoke at a rally attended by 17,000 people and called for a citywide march. He said:

“One day our society will come to respect the sanitation worker if it is to survive, for the person who picks up our garbage, in the final analysis, is as significant as the physician, for if he doesn’t do his job, diseases are rampant. All labor has dignity.”

His speech triggered national media attention, and catalyzed the rest of the labor movement to expand its support for the strikers.

King returned to Memphis on Thursday, March 28, to lead a march. The police moved into crowds with night sticks, mace, tear gas, and gunfire. The police arrested 280 people. 60 were injured. A 16-year-old boy, Larry Payne, was shot to death. The state legislature authorized a 7 p.m. curfew and 4,000 National Guardsmen moved in. The next day, 300 sanitation workers and supporters marched peacefully and silently to City Hall — escorted by five armored personnel carriers, five jeeps, three large military trucks, and dozens of Guardsmen with bayonets fixed. President Lyndon Johnson and AFL-CIO President George Meany offered their help in resolving the dispute, but Mayor Loeb turned them down.

King came back to Memphis on Wednesday, April 3 to address a rally to pressure city officials to negotiate a compromise solution to the strike. That night, at the Mason Temple — packed with over 10,000 black workers and residents, ministers, white union members, white liberals, and students — King delivered what would turn out to be his last speech. He emphasized the linked fate of the civil rights and labor movements:

“Memphis Negroes are almost entirely a working people. Our needs are identical with labor’s needs — decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community. That is why Negroes support labor’s demands and fight laws which curb labor. That is why the labor-hater and labor-baiter is virtually always a twin-headed creature spewing anti-Negro epithets from one mouth and anti-labor propaganda from the other mouth.”

The next day, James Earl Ray assassinated King as he stood on the balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Hotel.

As Time magazine noted at the time: “Ironically, it was the violence of Martin Luther King’s death rather than the nonviolence of his methods that ultimately broke the city’s resistance” and led to the strike settlement.

President Johnson ordered federal troops to Memphis and instructed Undersecretary of Labor James Reynolds to mediate the conflict and settle the strike. The following week, King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, and dozens of national figures led a peaceful memorial march through downtown Memphis in tribute to King and in support of the strike. Local business leaders, tired of the boycott and the downtown demonstrations, urged Loeb to come to terms with the strikers.

On April 16, union leaders and city officials reached an agreement. The City Council passed a resolution recognizing the union. The 14-month contract included union dues check-off, a grievance procedure, and wage increases of 10 cents per hour May 1 and another five cents in September. Members of AFSCME Local 1733 approved the agreement unanimously and ended their strike.

The settlement wasn’t only a victory for the sanitation workers. The strike had mobilized the African American community, which subsequently became increasingly involved in local politics and school and jobs issues, and which developed new allies in the white community.

Like the civil rights movement of the 1960s, there is a growing movement in the United States today protesting the nation’s widening economic inequality and persistent poverty.

One of the most vibrant crusades is the ongoing battle to raise the minimum wage. In the past 40 years, the federal minimum wage — stuck at $7.25 since 2009 because Republicans in Congress have refused to act — has lost 30% of its value.

As a result, low-wage workers for fast-food chains and big box retailers, janitors, security guards, day laborers, and others have forged a grassroots movement to pressure their employers (like Walmart and McDonalds) to raise starting salaries and benefits. These workers and their allies have engaged in civil disobedience and strikes to galvanize public opinion.

Coalitions of unions, community organizations, faith-based and immigrant rights groups have also successfully pushed cities and states to adopt minimum wage laws that will pay families enough to meet basic needs. A growing number of cities — including Seattle, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Chicago, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Pasadena, and many others — have passed minimum wage laws that will gradually reach between $13 and $15 an hour, typically with an annual cost-of-living increase. Los Angeles County — the nation’s largest county — adopted a law that will raise the minimum wage to $15 in unincorporated areas. Last year California and New York adopted state laws to bring the minimum wage to $15 an hour. Raise Up Massachusetts, a coalition of community groups, faith-based organizations, and unions, is sponsoring a ballot measure next year that would raise the state’s minimum wage from $11 to $15 an hour by 2022 with a $1 increase each year starting in 2019. Twenty-nine percent of the Massachusetts workforce would see increased wages under the initiative, affecting roughly 947,000 workers.

A Pew Research Center survey last year found that 52% of American voters favored raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour. An even larger number of Americans embrace increasing it to $12 an hour. Backed by nearly half of the Senate’s Democrats, Senators Bernie Sanders and Patty Murray have introduced the Raise the Wage Act of 2017 which would gradually raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024.

In recent years, New York, California, Massachusetts, and Hawaii have adopted different versions of the Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights that provides new protections for nannies, babysitters, senior care aides, housekeepers and others — primarily women and many of them immigrants — who are excluded from federal labor protections.

Several states — including California, Rhode Island, Washington, New Jersey, New York, and the District of Columbia — have adopted paid family leave laws. A growing number of cities (including Philadelphia, Austin, Seattle, Cincinnati, Kansas City, Portland (Oregon), Chicago, Minneapolis, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C), and counties (including Missoula County in Montana, Pima County in Arizona, and Kings County in Washington), have adopted laws providing government employees, and in some places all employees, with paid family leave.

These laws require employers to pay workers’ salaries if they take time off from work to care for a new child following birth, adoption, or foster placement, to recover from a pregnancy or childbirth-related disability, and/or to take care of sick family members. This is a right that workers in most other countries already take for granted. As the number of cities and states with such laws continues to grow, Congress will be under increasing pressure to adopt similar policies at the federal level.

Of course, President Trump and the Republican Congress are trying to roll back worker protections against wage theft, health and safety dangers at the workplace, and threats to retirement security. Trump has appointed anti-union members to the National Labor Relations Board who will seek to weaken rules protecting workers.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” King wrote in his Letter From Birmingham Jail. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Just as King helped build bridges between the labor and civil rights movements, today’s union activists are forging closer ties to the immigrant rights, women’s rights, and environmental justice movements, as well as to struggles to reform Wall Street and to challenge the proliferation of guns and the mass incarceration of people of color.

In his final speech at Memphis’ Mason Temple on April 3, 1968, King, only 39 at the time, told the crowd about a bomb threat on his plane from Atlanta that morning, saying he knew that his life was constantly in danger because of his political activism.

“I would like to live a long life,” he said. “Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And he’s allowed me to go up to the mountain, and I’ve looked over, and I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the promised land.”

We haven’t gotten there yet. But King is still with us in spirit. The best way to honor his memory this Labor Day and every day is to continue the struggle for human dignity, workers’ rights, living wages, and social justice.