Last week, 35 former Atlanta educators were forced to take a perp walk, reporting to law enforcement authorities for arrest in connection with the nation’s biggest (so far) academic scandal. It was a disturbing spectacle. Once among the pillars of metro Atlanta’s middle class, they’ve been reduced to pleading that they don’t belong in jail.

And that may be true. The charges of a widespread conspiracy to cheat may represent the ambitions of a local prosecutor rather than any top-down plot carried out by a confederacy of criminals. But I don’t waste sympathy on the defendants: They deserve the ignominy of association with thugs.

I’m reserving my pity for the students in Atlanta’s public schools. They’re the victims of this massive fraud, the helpless pawns of adults who callously overlooked the needs of their charges and focused on preserving their careers.

Unfortunately, that’s been a recurrent theme in 40 years of school-reform efforts across the country. Whether represented by unions or organized as a powerful voting bloc or both, public school educators have put their paychecks front and center, discounting the needs of their students. Even good teachers — dedicated, hard-working and inspiring ones — have rallied to protect their peers, some of whom don’t deserve their support.

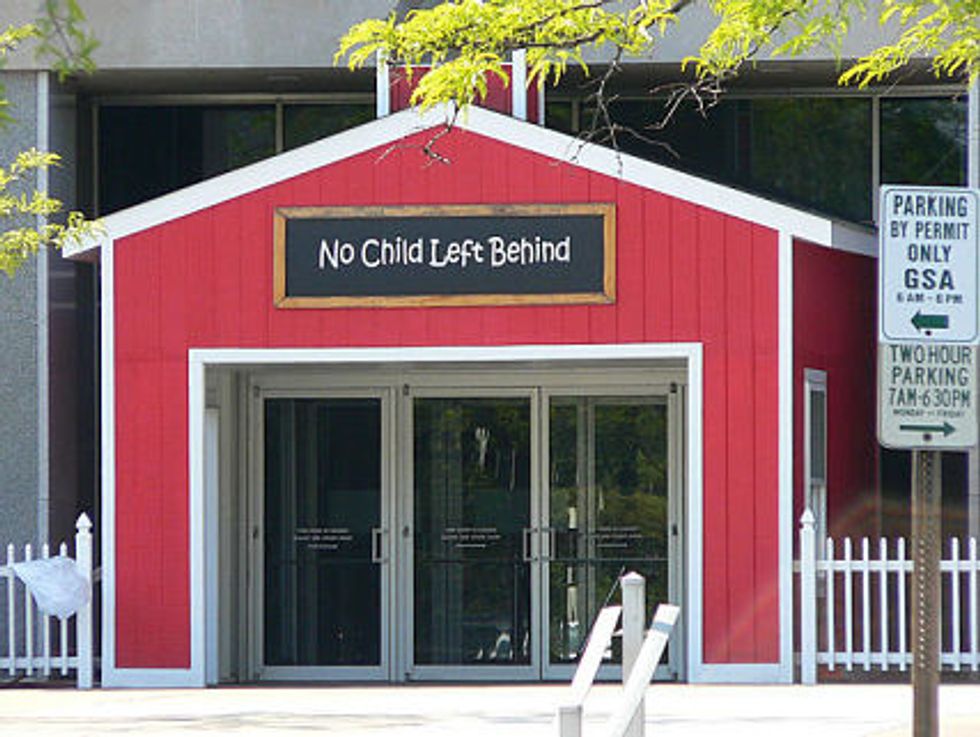

Atlanta’s scandal has reinforced long-standing criticisms of widespread testing in schools, a strategy that was exalted by George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act. The critics are right: The overdependence on standardized tests has calcified instruction, failed students and encouraged fraud. Educators in poor neighborhoods, where students are more likely to score poorly, are singled out for official reproach.

Conversely, teachers, principals and superintendents who show miraculous results — turning failing students into suddenly brilliant ones — are showered with praise, promotions and, frequently, money. It’s no wonder, then, that some Atlanta teachers had after-school “parties” where they erased students’ answers and replaced them with the correct ones.

While Atlanta may have the best-documented case of test-related fraud, it’s by no means the only one. In an exhaustive investigation published last year, USA Today found evidence of fraudulent test scores in six states and Washington, DC. Even the vaunted Michelle Rhee, who led a reform effort in Washington, has been implicated, accused of turning a blind eye to suspicious test results.

But for all the problems associated with No Child Left Behind, Bush deserves credit for this much: He recognized the failures of public schools that are not doing very much to educate children from less-affluent homes. He described a culture freighted with “the soft bigotry of low expectations,” a phrase that still rings true.

For years, too many teachers in low-achieving schools have blamed their failures on children and parents, describing homes in which discipline is poor, mediocrity is lauded and failure is acceptable. If those teachers believe there is nothing to be done to improve the academic standing of those children, why teach? If the children are too “dumb” or too deprived to profit from their instruction, why do they stay?

Reams of research bear out the complaints of educators who say teaching poor kids is challenging: Children from less-affluent homes are more likely to read below grade-level, to need special help, to score poorly on standardized tests. But that hardly means they can’t learn.

They need teachers who believe in them. Those who believe they’re being unfairly tarnished by unworthy students don’t fit the bill. As psychologists point out, kids pick up those signals easily enough and behave as the teachers expect them to. In other words, they learn little or nothing.

In addition to dedicated teachers, those children need a community that’s also committed to them. That includes the politicians, activists and church groups who spend an inordinate amount of time defending educators rather than demanding good schools for the kids.

As Atlanta’s disgraced educators surrendered last week, a group of activist preachers — Concerned Black Clergy — assembled to suggest that racism was involved. “Look at the pictures of those 35,” said the Rev. Timothy McDonald. “Show me a white face.”

Would that McDonald and his allies were as concerned about Atlanta’s public school students, 80 percent of whom are also black.

(Cynthia Tucker, winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, is a visiting professor at the University of Georgia. She can be reached at cynthia@cynthiatucker.com)

Photo of Department of Education via Wikimedia Commons